Survivors retell story of Quake Lake 60 years later

Montana landscape changed in night of terror Aug. 17, 1959

EARTHQUAKE LAKE, Mont. — Anita Painter Thon remembers the dinner she ate the night everything changed. She and her twin sister — they’d just turned 12 — wanted hot dogs, but they couldn’t convince their parents. Instead, it was steak and potatoes, cooked over a campfire in a campground next to the Madison River.

The family had driven up from Ogden, Utah, to spend part of the summer of 1959 in Yellowstone. After some time in the park, they decided to camp in the Madison Canyon, downstream of Hebgen Lake. Her father had heard the fishing was good.

After dinner — which Thon said was wonderful, despite any discontent at the time — they cleaned up camp. A ranger had warned them of bears. Then they got into their camp trailer and went to bed.

Just before midnight, the trailer started shaking. Thon woke up. She initially thought it was their dog, Princess, but she also heard a loud roar, the Bozeman Daily Chronicle reported.

“It sounded like a train coming toward our trailer,” she said.

Bonnie Schreiber and her parents woke up, too. They were in a different trailer in the same campground, called Rock Creek. Schreiber was 7. Her father thought the noise might be a bear messing with their cooler, so he jumped out with a hammer, ready for a fight.

He didn’t see a bear. But the trailer was a few feet off the ground.

In a spot on a ridge there was Tootie Greene, a 30-year-old nurse from Billings. She was there with her husband and 9-year-old son, a few days from the end of their vacation. She said the ground was rolling like ocean waves. The next thing she saw was water.

“I drew a blank after that for a while,” Greene said.

An earthquake had disrupted the full-moon night of Aug. 17, 1959, turning it chaotic and terrifying. The quake had a magnitude of 7.3, and it remains the largest to hit the region. Rocks, trees and earth shook loose at the western end of the canyon, forming a massive landslide. The slide went three-quarters of a mile north and spread a mile east to west, burying 19 people. Nine more died because of the quake, including Schreiber’s grandmother and Thon’s mother.

The landslide also stopped the river. The water backed up and spread out, turning a swath of canyon into an ominous lake. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ultimately cut a spillway.

Sixty years later, the lake is still here, a symbol of force, havoc and tragedy.

Visitor center tells story

The road between West Yellowstone and the young lake takes people through the highlights. There’s Refuge Point, a spot above Hebgen Dam where survivors like Thon, Schreiber and Greene congregated that night until help arrived the next day.

Downhill is the new Beaver Creek Campground. The old one is underwater.

West of there, it follows the shore of the 60-year-old lake, dead trees poking through the surface. Then the slide itself comes into view, a big barren patch on the otherwise forested canyon wall.

The Earthquake Lake Visitor Center is on the other side of the road. Built in 1967, it’s the domain of Joanne Girvin, who runs the center for the Forest Service. She has worked here since 1991. She has told and retold the story of the quake, and she knows it well.

“There’s two sides to the story,” she said, sitting on a bench outside the center earlier this month. “It’s the human story, and it’s the geologic story.”

The geologic story is one of power — how the quake is still the largest recorded in the Rocky Mountain states, how Hebgen Dam didn’t break, how the slide carried 80 million tons of rock. There are big boulders above the center that show how high the slide climbed, including one that’s dedicated to the people who died here.

The human story is one of terror — buried campsites, falling boulders, trees pinning down people and cars. The water backing up and rising. Chunks of highway disappearing, leaving people with no way out.

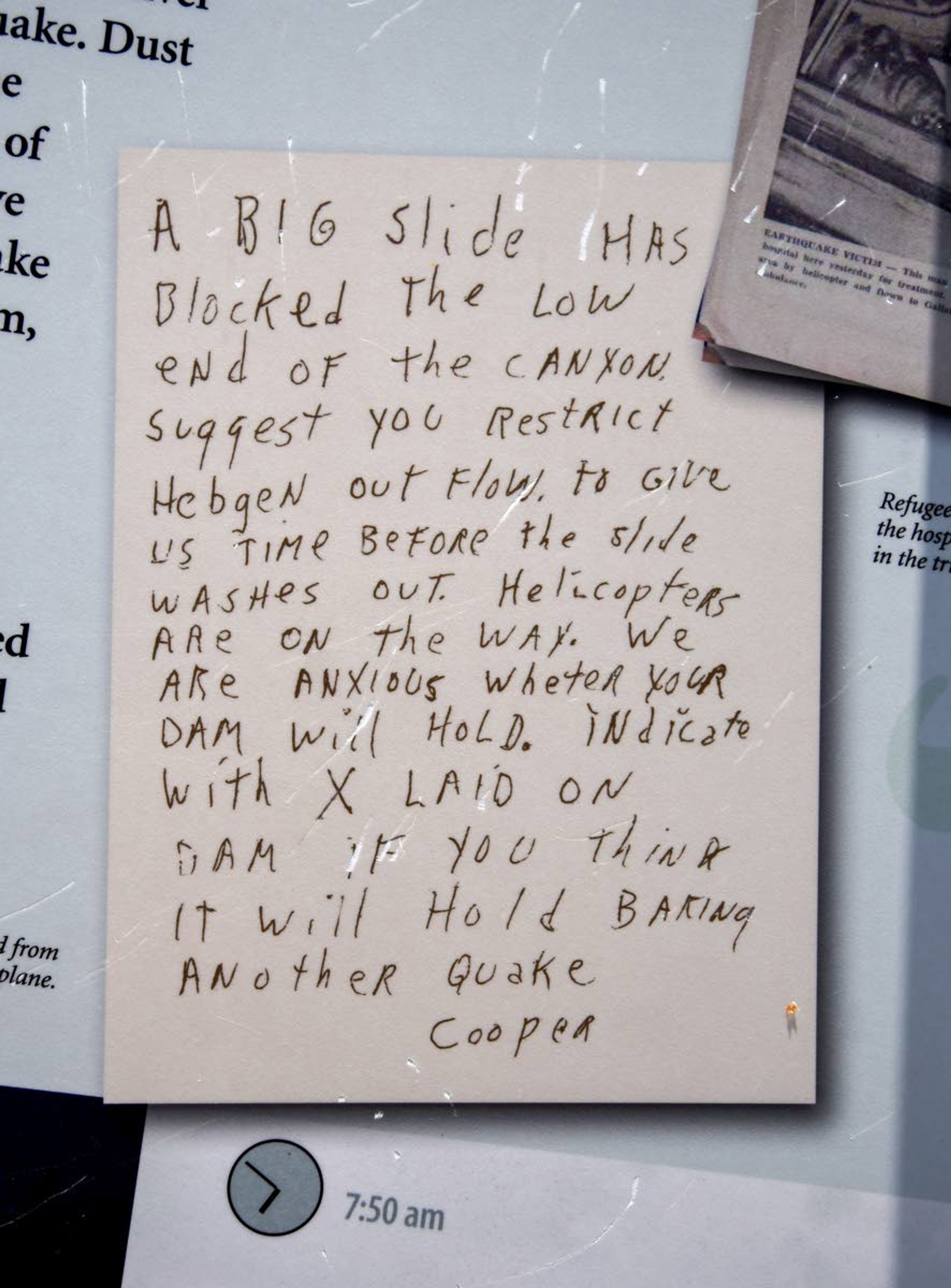

“You had 250 people who were trapped between the dam and this massive landslide,” Girvin said.

Survivors recall chaos, fear

After waking up to the roar and the shaking, Thon remembers falling into the river with her twin sister. They were crying, wondering what had just happened. She saw a woman in a white robe float by on top of something, smoking a cigarette.

“She goes, ‘Stop crying, you’re going to be OK,’ ” Thon said.

When they got out of the water, the air smelled of dirt and gasoline. They couldn’t find their parents or older sister. They checked the trailer, which was in the water, but had no luck.

Then they heard their sister call to them from above. She’d found their mother, whose arm was injured badly. She’d also found a nurse who’d been camping there — Tootie Greene.

“That was the first one I started taking care of,” Greene said.

Greene is from Billings. Fallen trees blocked their station wagon from moving, so she, her husband and their son hurried to higher ground.

Soon, she became the emergency medical care for more than a dozen people. The injuries varied.

“There were deep body wounds, to the leg or the back and the chest and the arm,” Greene said. “One guy almost lost his thumb. Another guy lost an ear.”

She cared for them well into the next day, until a helicopter carried some people away and a road was cut to West Yellowstone.

That’s how Schreiber got out. She’d been cut badly on the right side of her head. She was later told the back of her eyeball was visible.

In West Yellowstone, she was put on a plane to Bozeman, where she went to the hospital. Everything healed fine. She said this week she thinks she sees better out of her right eye.

But her grandmother wasn’t fine. She died in the hospital. Schreiber remembers seeing her all cut up immediately after the quake, and that her mother was hauling both of them toward help.

“And that’s the last time I seen my grandma,” she said.

Thon’s mother died in Bozeman, too. Her arm was the main injury, but Thon said it got a nasty infection that never healed. Thon and her sisters were at their aunt’s house back in Utah when they got the bad news a few days after the quake.

She still misses her.

“She was just a wonderful mom. She would have made the best grandmother,” Thon said. “She was like the glue that held us together.”

Tragedy lived on for many

The earthquake lasted about 20 seconds, according to Girvin. Aftershocks came the next day, some pretty strong, and minor quakes continued long after.

“It shook for a good month after the quake,” Girvin said.

People moved on. But tragedy always lingers.

Schreiber misses her grandmother. She remembers sneaking out of the camper early in the morning to go fishing with her. The quake took that from her.

It also left some lasting fear inside her, at least according to her mother.

“Mom said whenever the wind would blow or rattle a window, I’d start crying and screaming and stuff,” Schreiber said. “I don’t remember any of that.”

She now lives in Checkerboard, with a blue heeler. She has earthquake insurance and she avoids parking near boulders.

Greene, who turns 91 next month, said she wasn’t too bothered by it in the years that followed, but her husband and son were. She said her son didn’t go back to the area until adulthood, and her husband never wanted to talk about it. It makes sense to her — they’re victims of the quake, too.

But that’s not really how it’s been for her, other than some lost sleep.

“I deal with things as they come,” Greene said. “Of course, I spent lots of nights that my brain doesn’t turn off ... just reliving what happened that I remembered.”

Thon’s family was never the same. Her father recovered and returned to Ogden, but he was depressed. He ran a gas station, and Thon said there were times he’d thought of blowing it up.

“It was just really bad,” Thon said.

Things eventually improved. He remarried during her senior year of high school, found some happiness. She and her siblings — the two sisters and a brother who wasn’t at the quake — made lives of their own.

She’s been married 49 years now and has a family. Still lives in Utah. She’s written a few books about the earthquake in the past decade, telling her story and the story of those who died. Writing about the experience was something she’d always wanted to do.

But she didn’t revisit the site of the earthquake until 36 years later.

In 1995, her son got engaged and the family took a trip to Yellowstone. They decided to swing through the canyon, and she remembers sitting in the car as it rounded a corner and the lake came into view. It was the first time she’d seen it in daylight.

“I couldn’t even talk,” she said. “It was paralyzing.”

They stopped at a roadside sign that described the “night of terror.” She’d been trying to keep it together. But it couldn’t last.

“I looked at that sign and I looked at the slide and I just started crying,” she said.