‘Waltons’ fans revel in this museum

SCHUYLER, Va. — Deep in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, miles from any multilane highway (or any straight road for that matter), through dense forests of Virginia pine and over trickling streams, I heard a familiar voice.

“Illi-noa? Why that’s a ways away from he-uh, suh.”

The woman at the front desk of the tiny museum I was visiting sounded like Thursday night TV, 1973. Her soft Southern accent where “house” is “hoose” and father is “fah-tha,” shaped by the Scots who settled this area, had the same soothing effect as the voice of local hero Earl Hamner Jr., creator and narrator of “The Waltons,” did on American television viewers.

The homespun show about a large, Depression-era family in Appalachia snuck onto the TV scene in the fall of 1972. “The Waltons” was based on Hamner’s childhood here in Schuyler, population now 298. Though the series was rooted in his 1961 novel “Spencer’s Mountain,” Hamner would write only a handful of the TV drama’s 200-plus episodes. But he wielded great influence as executive producer and as “The Waltons” weekly narrator.

The series went off the air decades ago but it continues to resonate with fans, many of whom are expected to gather in Hamner’s hometown this fall for the inaugural Forever Friends of The Waltons weekend, when a “Waltons”-themed bed and breakfast will celebrate its grand opening in Schuyler, about 25 miles southwest of Charlottesville.

Since the ’90s, the centerpiece of Schuyler (pronounced SKY-ler) has been the Walton’s Mountain Museum, housed in Hamner’s former red-brick grade school.

Visitors enter the building into the school’s time-capsule gym decorated with class photos of mountain kids going back decades. Inside the classrooms are re-created sets from the show, which was filmed in California. There’s the bedroom of eldest son and budding writer John-Boy, complete with the desk positioned against the window and the Boatwright college pennant pinned to the wall. Over in another classroom, the Waltons’ living room features a console radio in the corner and doilies galore. The kitchen and eating area include a long, wooden dining table with bench seats replicating where some of the show’s best meaning-of-life, right-or-wrong dialogue took place. A camera and dolly used in 182 episodes hunkers in the corner.

The camera contraption is one of the museum’s few actual pieces from the show. Most of the props were owned by the studio and either re-used in other programs or junked. But the large-scale sets are built with period pieces similar to the Hollywood props used in filming; like the contraption the clueless Baldwin sisters used to produce high-octane “Papa’s Recipe” the museum features an authentic moonshine still seized by local authorities.

The unlikely story of “The Waltons” as entertainment is also presented through displays and film. When it debuted on CBS, the program was little noticed against NBC’s variety show hosted by cutting-edge comedian Flip Wilson and ABC’s counter-culture crime drama “The Mod Squad.” But some critics touted “The Waltons” as refreshing, and it developed a faithful though small audience.

So desperate was the network in that first year to keep it on the air, it took out an ad that said, “Some people here at CBS believe there are enough of us around — even in this super-sophisticated day and age — who can still respond to some old-fashioned notions like respect and dignity and love.”

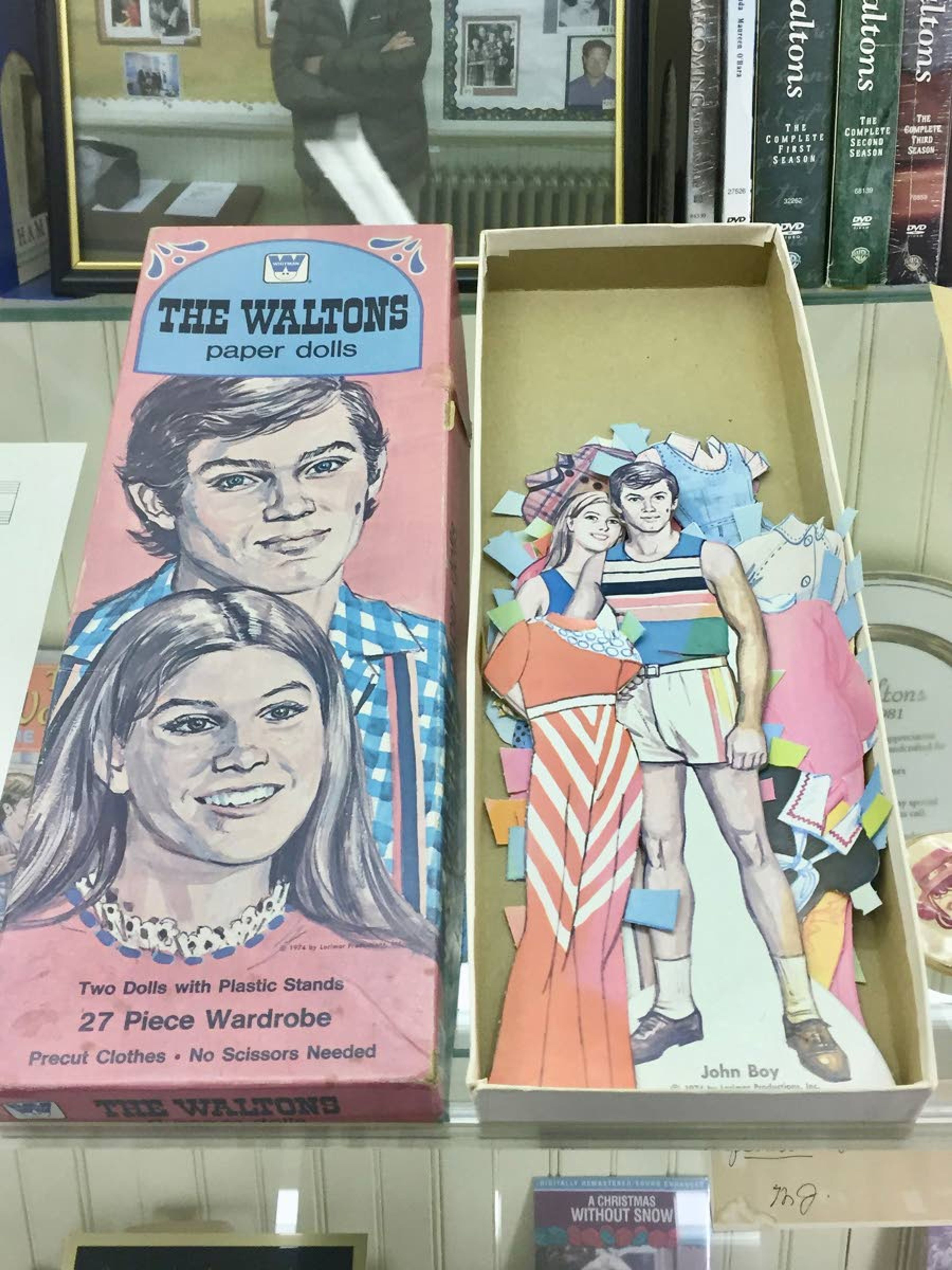

Indeed, there were: In its second season, “The Waltons” rose to No. 2 in the ratings, with some 28 percent of the viewing public tuning in. Over nine seasons, the show would win 13 Emmys and spawn a plethora of products, including lunch boxes, board games and paper dolls, some of which are on display in the museum. The show also coined an enduring phrase, “Good night, John-Boy.”

That’s the fictional part of the Waltons. Down the street is the actual home where Hamner grew up, and it’s open to visitors ($10). Built in 1915, the modest two-story structure housed Hamner, his seven siblings and his parents. Wrapped by a front porch that will look familiar to fans of the show, the house was purchased in 1929 by the writer’s father, Earl Sr., who worked as a machinist at the local soapstone company. A green 1929 Ford pickup truck, like the one used in the show, sits outside.

A trio of fans bought the home from a Hamner relative in 2017 and added period furniture, Hamner family photos and signed pictures from the show’s actors, some of whom have visited Schulyer for Waltons-related events. The Walton Hamner House manager Laurie Lane tells visitors stories of the Hamner family, and her thorough presentation is a delight for knowledgeable fans.

An “Ike Godsey’s General Merchandise” shop is located nearby, selling Waltons books, CDs and videos, the Baldwin sisters’ recipe and mountain-themed gifts.

Named after the mother and father on “The Waltons,” John & Olivia’s Bed & Breakfast Inn is accepting reservations for stays beginning Nov. 1. The new B&B is designed to evoke the Waltons era. Guests can stay in one of five rooms: the Writer’s Room, the Parents’ Room, the Boys’ Room, the Girls’ Room and the Grandparents’ Room.

The B&B is scheduled to be dedicated in Schulyer in connection with the Forever Friends of the Waltons event, Oct. 25-26. The weekend festivities include a luncheon, autograph sessions and appearances by “Waltons” actors Jon Walmsley (Jason), Kami Cotler (Elizabeth), Eric Scott (Ben), Mary McDonough (Erin), and Judy Norton (Mary Ellen), among other things.

Cotler, who played the youngest of John and Olivia Waltons’ brood, lives in California. But she spent some time as an adult living in the Blue Ridge Mountains, drawn to the scenery she’d heard so much about on set.

“As a child on ‘The Waltons,’ I listened to dialogue describing the leaves turning or the dogwood blooming and kind of wondered why we kept talking about foliage,” she said in an email. “Then I realized it’s worth talking about the beauty of the place as the seasons turn.”

Cotler said events like the one coming up in October are “like a family reunion” for the cast.

“Earl actually assembled random strangers and we became a family,” she said. “I can’t explain how. Maybe it was the words we said or the characters we played or the gentle tone Earl set.”

Years before his death in 2016, I asked Hamner in an interview if he thought the show influenced parenting and expectations of family life. He responded that television was a powerful thing, but he suspected more American parents were already like John and Olivia Walton. They just needed a little recognition.

At a museum event in 1997, Hamner told the audience that even though many people outside of the Blue Ridge Mountains thought he “talked funny,” the stories of the region had widespread appeal.

“In every country around the world that has a television station, this community, this small village in the heart of Nelson County, has come to be synonymous with family values,” he said. “I think I had something to do with spreading that news, and I’m proud of that.”

Herrmann is a freelance writer. The museum's website is walton-mountain.org.

TNS