Then & Now: Sudden death

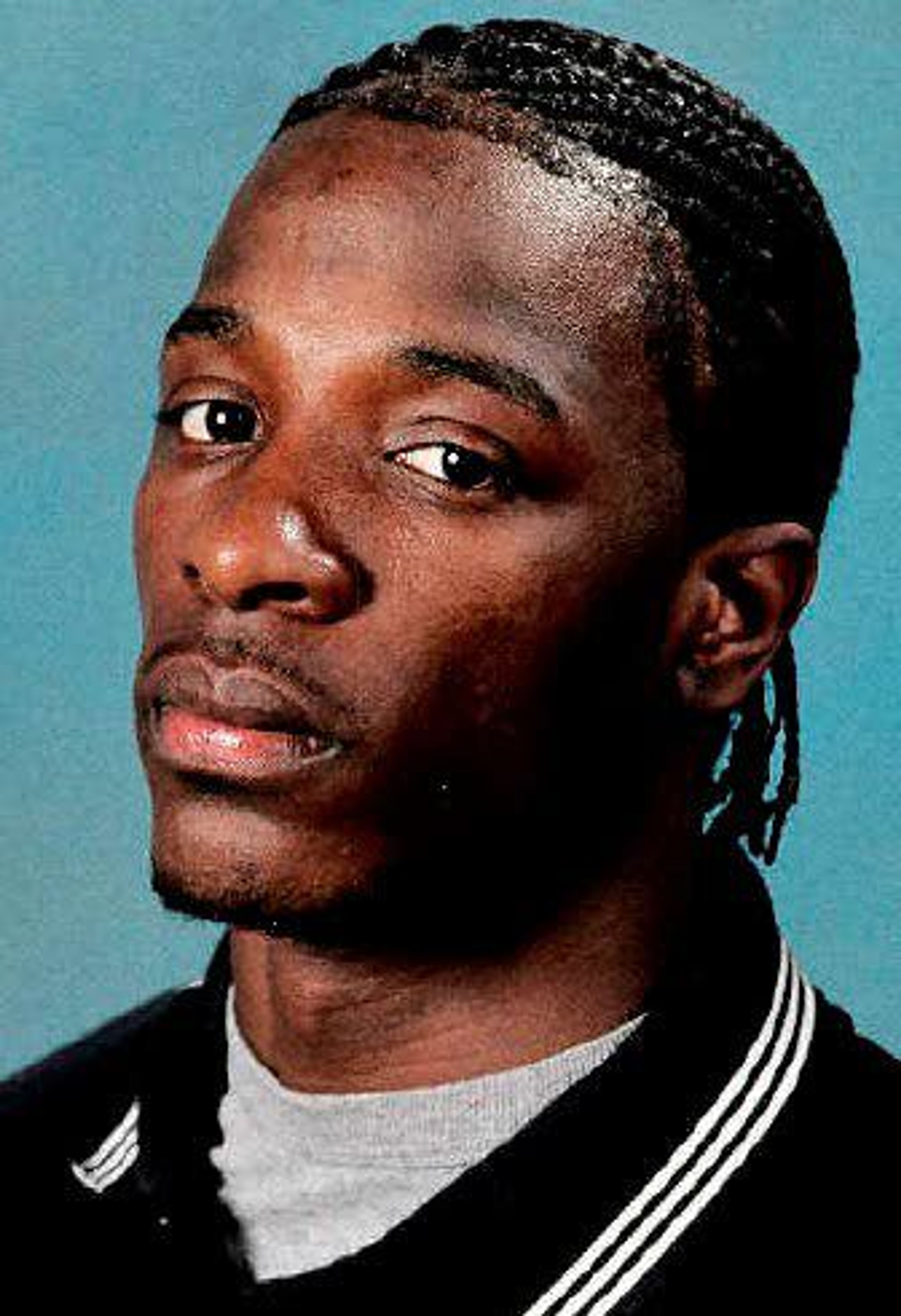

Shock, grief over Eric McMillan’s murder still reverberating among his former teammates, as well as those who knew him in Alabama

Then: This story originally ran Nov. 1, 2004, in the Lewiston Tribune.

TUSKEGEE, Ala. — Eric McMillan’s body lies under 6 feet of gritty Alabama topsoil. A majestic oak tree provides the backdrop for his final resting place, where he has joined the grandmother who helped raise him.

Six weeks ago, the hardscrabble streets of Tuskegee were a world away from McMillan, a 19-year-old starting cornerback for the University of Idaho football team.

He was realizing his dreams of getting a college education, working toward his goal of playing in the National Football League. He was a budding leader on the field and an extremely well-liked member of the UI community.

But an inexplicable turn of events brought an abrupt end to McMillan’s life, the circumstances of which are still being pieced together by investigators in Moscow.

Two brothers from Seattle are the primary suspects in McMillan’s untimely death. They were arrested after a high-speed chase that ended at a roadblock 140 miles from Pullman, where they were initially spotted in a white BMW similar to one witnesses reported seeing creep away from McMillan’s apartment complex immediately after the shooting.

While arrest warrants have been issued for Matthew and James Wells in connection with McMillan’s murder, no charges have officially been filed. It could be months, perhaps years before they step into an Idaho courtroom.

In the meantime, the Wellses will likely remain behind bars in Washington, where they are being prosecuted on a felony count of eluding police.

As for McMillan, his permanent address is little more than a mile from the dilapidated single-wide mobile home he grew up in, at a place called Chehaw Memorial Garden.

His grave remains unmarked, with the exception of a small aluminum plate bearing his name and a fading wreath of artificial flowers.

———

Alundis Brice holds fond memories of his first conversation with McMillan, even though the latter didn’t have much to say.

The newly hired Idaho cornerbacks coach was sitting at his desk when head coach Nick Holt burst into his office and asked, “Where’s Eric?”

“Who’s Eric?” Brice said. “And he says, ‘He’s one of your guys that didn’t show up.’ So I had to call him up and fuss at him on the phone and say, ‘Hey man, get on the bus and get up here.’ ”

Once he arrived on campus, McMillan sought out Brice and offered an apology.

“I told him, ‘I don’t want to hear it — you’ve got to run.’ That’s how we started our relationship, and it skyrocketed from there,” Brice said. “He walked in here a couple of days later and said, ‘Hey coach, nobody ever talked to me like that before. I didn’t know how to act. I wanted to fight at first.’

“I’m like, ‘Eric, I love you to death, and we’re going to have a great relationship. But you can’t get anything over on me, Eric, because I’ve tried it all.’ ”

A former University of Mississippi standout who went on to play in the NFL, Brice knows what it takes to be a winner, and he has a Super Bowl ring to prove it.

Each day, Brice tries to pass that wisdom on to his players.

“I tell them all the time that they’ve got the best of both worlds,” Brice said. “They’ve got a coach that grew up just like they did, they’ve got a coach that played the same position they played, and they’ve got a coach that played in the (NFL), the same place they want to get to.

“And they also have a coach that got a degree from college, the same thing they’re trying to get.”

It didn’t take long for McMillan to endear himself to his coaches, Brice in particular.

“Our relationship was at times brother to brother, at times coach to student, at times friend to friend. Sometimes dad to son,” Brice said. “So we had a lot of different roads.”

But early in the evening on Sept. 20, Brice’s phone rang unexpectedly. It was Idaho safety Simeon Stewart, calling to tell him McMillan was in the hospital.

“I was like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me,’ ” Brice said. “I jumped up and walked in there to coach Holt’s office and I say, ‘Hey coach, I think Eric just got shot. I don’t know, it ain’t clicking with me yet.’ ”

———

McMillan made a habit of reaching out to people, offering support and encouragement in times of need.

His first contact with Chris Kehne came during their senior year in high school, when they lined up against one another in an intraleague grudge match.

McMillan was a star defensive back for Murrieta Valley High in Murrieta, Calif., where he’d been relocated by concerned family members. Kehne was the go-to receiver for Chaparral High in nearby Temecula, Calif.

Their individual matchup had been hyped in the local newspapers, but wet, muddy conditions took the edge off their showdown.

“We didn’t do a lot,” Kehne said. “We were just kind of joking around about how Idaho was recruiting both of us.”

Both eventually signed on with the Vandals, but grade-related issues were leaving Kehne’s status up in the air.

“I was getting bad grades in a class and he found about it, so he started calling me about twice a week, checking on me and seeing if I was all right,” Kehne said. “He knew that if I didn’t pass the class, I wasn’t going to come up here.”

Kehne buckled down and became eligible, and he and McMillan shared a dorm room at Idaho the next fall.

“He was an awesome player, an awesome person,” Kehne said. “And a great roommate.”

Although they didn’t reside together this season, Kehne and McMillan remained close.

Kehne was at home studying when he learned McMillan had been shot. He dropped everything and ran to Moscow’s Gritman Medical Center, where he was joined by several of his coaches and teammates.

“A nurse came out and said he’d survive surgery, and that we’d be able to see him as early as 8:30 in the morning,” Kehne said. “And then I remember coming home from class the next morning and finding out he’d died.

“It really didn’t hit me for a while,” he added, “and then about two weeks into it, I kind of lost it.”

———

A memorial service was held for McMillan two days after his death. Close to 500 people crammed into Idaho’s Hartung Theatre to pay their respects.

Tears flowed freely as friends and teammates shared their memories of McMillan, venting their frustration over his passing in the most positive manner possible.

When Brice took the stage and began to speak, the emotion began to swell. He told the audience he knew first-hand how McMillan felt when he was shot, how he felt on the operating table that fateful night.

Like McMillan, Brice had once taken a bullet in the chest. That shooting occurred while he was attempting to break up a fight in 1995, his senior year at the University of Mississippi.

“It’s really hard to explain to people,” Brice said. “If I looked at you and said it really doesn’t hurt that bad when you get shot, you’d look at me like I was crazy. But you don’t really feel it. The pain comes when you wake up.

“I didn’t explain that then, because I couldn’t imagine the idea of somebody going through what I went through. I remember lying in intensive care and the nurses coming in every 30 minutes saying, ‘We’ve got to turn you over because you’re going to get bedsores,’ and I’ve got tubes all over my body ... and every inch of my body is hurting because I can’t move myself and I’m on a ventilator with all these tubes down my throat.”

The pain Brice felt then wasn’t unlike the pain he felt when McMillan died.

“The thing that I regret more than anything in life is that young man died by himself,” Brice said. “I remember going to curl up back up in my bed after I found out he died and thinking that nobody was there to hold his hand, just nurses and doctors, because they wouldn’t let us go up.

“You know, nobody got to hear him say his last words. He had to die by himself, or with people he didn’t know. Nobody got to say ‘Eric, it’s OK,’ or ‘Eric, we’re here.’ There were 60 or 70 people downstairs, and that man died by himself. He had to go from this earth not knowing where he was and not knowing that there were people downstairs crying and praying for him.

“I’m not mad at the doctors, because they’ve got their protocol,” Brice added. “But I wish they would have let me or coach Holt or somebody just go up there and hold his hand and just say, ‘Hey Eric, we’re here,’ because on this earth, he didn’t know we were. He probably knows now, but at that moment he had nobody.

“The part that hurts me more than anything is that we couldn’t be there to say goodbye right then, while he was still awake and could look and see us.”

———

Annette Richards is a deeply religious woman who drives a white Cadillac with a front license plate that reads, “You’ve got a friend in JESUS.”

She and her husband have a son who is buried near McMillan at the relatively new Chehaw Memorial Garden, one of Tuskegee’s many segregated cemeteries.

Richards was McMillan’s godmother, and she still thinks of him as the outgoing, friendly child who grew up across the street from her home.

For the most part, McMillan was reared by his grandmother, Maggie, who died in 1999. McMillan’s mother wasn’t always around, Richards said, and he apparently had little, if any, contact with his father.

“Maggie raised him the best she could,” Richards said Saturday as she stood over both their graves. She’d already been at the small, tranquil cemetery once that morning, sprucing things up for a church memorial that was to be held on Sunday.

“He loved sports when he was here, and he always went to Sunday school,” Richards said. “I did what I could to help out.”

Richards said she was stunned when she learned that McMillan had been killed.

“I’m still shocked,” she said. “I’d like to know what happened.”

According to Richards, McMillan was spirited out of Tuskegee not long before he started high school. Relatives figured he’d have a better life in California, an opportunity to make something out of himself at the very least.

Six years later, he was well on his way — in northern Idaho, of all places.

———

Several of McMillan’s closest friends and teammates have memorialized him in tattoo form, and a decal bearing his number and initials is on the back of every Idaho helmet.

While the team was devastated by McMillan’s death, the Vandals went out and played a game at Oregon the following weekend.

By coincidence, it was Brice’s turn to deliver that week’s pregame pep talk.

“The first thing I said was that I grew up and went to school with a guy by the name of Chucky Mullins, who died at Ole Miss, and I used to hate it when coaches got up there and said, ‘Let’s win this one for Chucky, because he died,’ ” Brice said. “Well, Chucky would have never said that.

“So I got up there and the first thing I said was, ‘The one thing I’m not going to say is let’s go win this game for Eric, because I don’t want to win this game for Eric. I don’t want to play for Eric.’ But I told those guys to play with Eric. Eric may be gone in body, but he’s always going to be with us in spirit.

“He’s going to be part of me for the rest of my life. No matter where I go, I get to take Eric McMillan with me, in my heart, because he was a special guy. And he was a guy that I’ll never ever forget, because if I close my eyes, I see his smile.”

Brice plans to get his tattoo at the end of the season. He still includes McMillan on all his charts and game plans.

“Everything I write up has got Eric’s name on it,” Brice said, “because he’ll forever be part of this team, and he’ll forever be part of me.”

Idaho cornerback J.R. Ruffin, who started at cornerback opposite McMillan, shared much the same sentiment.

“I’ll always remember him; I’ve got a tattoo on my arm right here,” Ruffin said, pointing to his left biceps. “I’ll never forget him.”

Stewart and Ruffin have both said that McMillan was like a little brother. A little brother they often looked up to.

“He was a leader, even though he was (younger),” Ruffin said. “It’s like he was here before, you know what I’m saying? He knew stuff that we didn’t. It was like he was born again or something. That’s probably why he lived the way he did and did the special things he did. He helped us all.”

“All the stuff that he’d been through in his life, he didn’t hold that against nobody,” Stewart added. “He’d seen a lot of stuff over his life. But if his family situation was bad or whatever, you would never know that unless he told you. He never showed it unless you asked about it.”

———

After the shooting, McMillan stumbled down a flight of stairs, pleading for assistance.

“He said, ‘Help me, I’ve been shot,’ ” neighbor Jared Eaton told the Tribune a day after the incident.

It was Eaton who rushed McMillan to the hospital. He started going into convulsions along the way, and less than 12 hours later he was pronounced dead.

A popular theory is that the shooting stemmed from a Saturday night altercation at a Moscow nightclub called The Beach. According to most accounts, McMillan wasn’t directly involved. There’s widespread speculation that he was the wrong target, that his death was the result of a mistaken identity.

Brice was the football team’s lone representative at McMillan’s funeral. He was joined by Andrea Ausmus, the wife of Idaho speed and strength coach Aaron Ausmus.

Brice said he was looking for answers when he went to Tuskegee.

“You want to know why, and you want to know why you’re still here, and you walk up and see somebody lying in a casket that doesn’t look like him,” Brice said. “You close your eyes and all you can see is Eric’s smile when he walks in the room, or him when he’s sad and he’s got his head down thinking about something. Or him with his headphones on ...

“You know, that’s Eric McMillan to me. The kid that I’ve got to scream at sometimes, the kid that gave you that little smile when he knew that he was wrong, or when he knew that he was right he looked over there and was waiting for you to say, ‘Hey, great job Eric. Great job.’

“That wasn’t the same kid I saw lying there.”

Brice had individual meetings with his players last week, and said the effects of McMillan’s shooting are still felt on a daily basis.

“One of my questions was, ‘Hey, what’s going on in your life right now? You locking your doors?’ ” Brice said. “You know, because when I go home, I lock my doors now. Those guys never locked their doors. Nobody locked their doors around here. No need to. And it’s really sad that we had to learn a lesson by giving up one of the people that we loved the most.”

———

The week leading up to the shooting had been hard on McMillan. His mother was having an undisclosed surgery, and he wasn’t practicing well.

Brice expressed concern, but pressured McMillan to focus on the Vandals’ looming game against Palouse rival Washington State.

“He was slacking off in practice, and I’m yelling at him, I’m screaming at him, ‘Eric pick it up. Eric pick it up. Get it up, Eric.’ He goes out and drops his head. ‘No, get your head up, keep your head up. You’ve got to fight through this, Eric.’ And he starts to fight through it.

“And then he goes out and he has a great game.”

McMillan took every opponent seriously, but he placed particular emphasis on one date in particular — last Saturday’s contest against Troy University in Troy, Ala., which is just 70 miles south of his hometown.

“This week was going to be the first time his mom, his friends, his coaches from Alabama ever got to see him play football. Ever,” Brice said last Wednesday. “This kid knew that, and he was waiting for this week. He worked hard every day for this week, and now he’s not here, and that makes me sad because that young man fought hard for that. Really hard.”

Idaho lost the game 47-7, and a tailgate party that had been planned to celebrate McMillan’s homecoming never materialized.

Like many things in McMillan’s short life, his hard work and dedication went for naught, for reasons completely beyond his control.

None of it makes sense to Brice, or anyone else who knew McMillan. Perhaps it never will.

“That’s why I had to go to that funeral and say, ‘Hey Eric, we were there for you,’ ” Brice said. “We were there, and we’re still there, and we’re going to be there until the day we die.”

---

Now

James and Matthew Wells, both of Seattle, were convicted in 2005 of second-degree murder after admitting they both shot Eric McMillan.

McMillan was struck with a nonlethal shot behind the ear and a fatal shot to the chest, according to court records.

The Wells brothers said they went to McMillan’s off-campus apartment hoping to quell hostile feelings stemming from an earlier fight involving their younger brother, Aaron B. Wells, and their nephew, Thomas Riggins. As it turned out, McMillan had nothing to do with the fight and authorities said his death was mostly a case of mistaken identity.

James Wells was sentenced to eight to 20 years in prison and is on parole with no violations and is making regular restitution payments, according to court records. Matthew Wells is also on parole from an eight- to 20-year prison term with no reported violations and is also paying off restitution.