Right guy, right place,right time

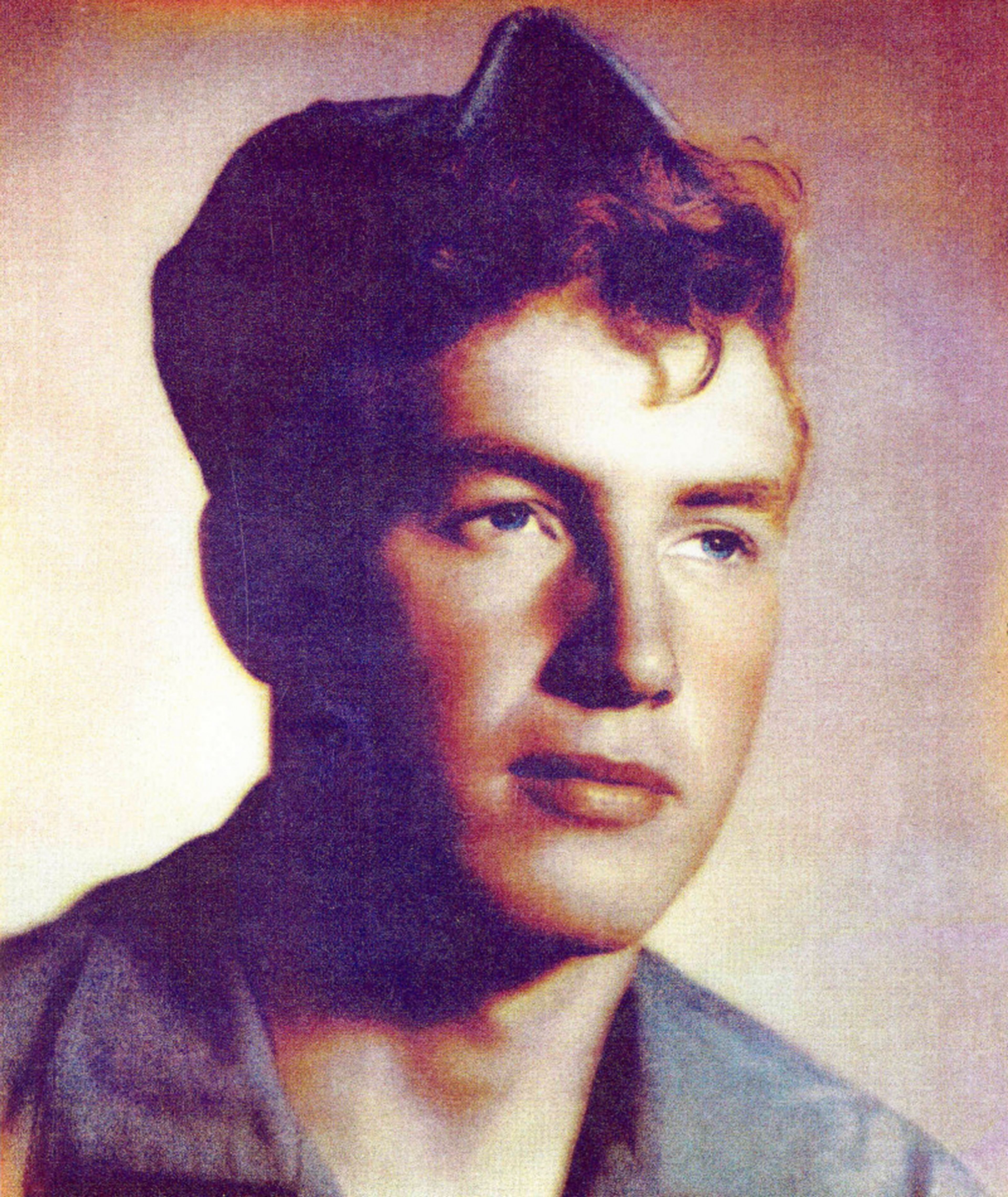

David Bleak was uncomfortable with the recognition he received for being awardedthe Medal of Honor

ARCO, Idaho — If the story of Idaho’s David Bleak weren’t true, you’d never believe it.

It’s a tale that begins in Korea, where a bloody war had become stalemated — after swinging back and forth from the Pusan Perimeter to the Incheon landing, from the Yalu River to the Chosin Reservoir — as it was about to enter its third year.

“By 1952, the front was pretty much solid. It was like a World War I positional warfare. There were not big changes,” said University of Idaho history professor emeritus Richard Spence.

With peace talks underway, it became a test of wills.

“From the end of ’51 to the middle of ’53, it’s either fighting while talking or talking while fighting,” Spence said. “It was a matter of keeping pressure on the other side until you got what you wanted at the peace table.”

Into that cauldron entered Bleak, who at 18 years old — five months after the war broke out — had quit high school, left his native Idaho Falls and enlisted, planning to become a tank mechanic. The sense of obligation to one’s nation ran deep among his siblings — all eight Bleak brothers served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. All survived.

At Fort Riley, Kan., Bleak’s superiors took a look at his 6 foot, 2 inch, 250-pound frame.

Here was a man strong enough to lift the rear of a disabled car while others braced it up to make repairs.

Here was a rancher who was the equal of any ornery Holstein.

While others doodled to pass the time, Bleak would bend a “church key” — a stainless steel can opener — between his index finger and his thumb.

And later in life when Bleak had grown weary of losing change in a vending machine at work, he single-handedly picked it up and threw it out of the trailer. The vending machine company took notice and replaced it with one that didn’t squander any more of Bleak’s quarters.

He was also a bit of a daredevil.

During winters in eastern Idaho, the Bleak boys would cut two holes in the frozen Snake River, dive into one and swim to the other — until their mother made them stop.

“It ran in the family,” Bleak’s wife, Lois, recalled. “He was as strong as an ox. I never saw anyone who was stronger.”

He was simply too large to work in a tank.

On the other hand, someone that powerful could be a godsend to an injured soldier who needed to be evacuated.

Declared the officials at Fort Riley: “You’ve just become a medic.”

It turned out to be a good call.

“He was just a person of service,” said Bleak’s granddaughter, Rose Beverly, of Richmond, Ky. “He was the kind of person, if you needed help, you called the right guy.”

By June 14, 1952 — Flag Day — Bleak had seen one fellow medic bleed to death because there was no one to attend to him. So when the call went out for a reconnaissance patrol to sneak behind enemy lines and capture a Chinese soldier for interrogation, Bleak joined 20 volunteers.

As they advanced upon Hill 499 in a northeastern area of Korea near Minari-gol, the Americans came under attack. Bleak attended to the wounded, only to find a trio of Chinese soldiers mowing down his comrades with automatic arms fire from the safety of a trench.

As a medic, Bleak carried no weapons other than a trench knife for cutting clothing away from wounds. But he lunged into that trench, breaking one Chinese soldier’s neck, killing the second by crushing his windpipe and dispatching the third with his trench knife. (His children say he was never without some kind of a knife again.)

As he returned to his fellow soldiers, a grenade bounced off a helmet and headed toward an American. Bleak shielded the man with his own body. Because it was a concussion rather than a fragmentation grenade, both men survived.

As the fighting continued, Bleak took a bullet in his left calf — leaving him with lifelong nerve pain. The medic lifted an incapacitated soldier over his shoulder and proceeded down Hill 499 — when two Chinese infantrymen approached him with fixed bayonets.

Bleak lowered the American he was carrying and charged the Chinese, grabbed each man’s head in one of his massive hands and smacked them together, killing both.

Here is one of life’s imponderables: Where did such a mix of physical courage, selflessness and empathy emerge?

“His blood was up,” said Bleak’s 61-year-old son Bruce Bleak, of Moore, Idaho. “It’s extraordinary, mind-boggling. He didn’t think he had done anything above and beyond. He was absolutely wrong about that.”

Although Bleak carried the wounded soldier to safety at the bottom of the hill and was seriously injured as well, he somehow failed to understand that all 20 of his fellow Americans — including as many as five wounded men — had returned alive.

“After he laid that man down, he turned around to go back,” recalled Lois Bleak. “It took five men to hold him down. ‘You have your own wound to take care of,’ they said.”

Final footnote: The squad managed to snatch a Chinese soldier.

“I remember that,” Bruce Bleak said. “They did succeed. I know that.”

From there, it was off to a Tokyo military hospital, where Bleak spent a couple months. By the time of his release, the battlefield commendation — initially his superiors recommended him for a Bronze Star — had begun making its way up the chain of command as the details of his exploits were verified. Within a year, by presidential proclamation, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

The citation read: “Sgt. Bleak’s dauntless courage and intrepid actions reflect utmost credit upon himself and are in keeping with the honored traditions of the military service.”

Bleak wrapped up his military service at about the same time the war ended with an uneasy armistice July 27, 1953.

“He’d done his part,” Bruce Bleak said. “There’s not much call for medics in peacetime.”

Three months later, Bleak joined six other Medal of Honor recipients at the White House. Not only did he tower above everyone, but the shy Idahoan looked as if he would have preferred being anywhere else.

But a smile came across his face as President Dwight Eisenhower whispered in his ear: “You’ve got a damned big neck.”

The president, a five-star general who never encountered a bullet fired in anger, seemed to marvel at these men:

“As we assemble on such an occasion, I think there are a number of thoughts that must cross our minds. One of the first and natural ones is that if you ever have to get in a fight, you would like to have these seven on your side.

“Certainly we view with almost incredulity the tales that we hear told in these citations. It seems impossible that human beings could stand up to the kind of punishment they received and deliver the kind of service they have.

“But I think the most predominating thought would be: Could we be so fortunate that this would be the last time such a group ever gathered together at the White House to receive the Medal of Honor, a battlefield decoration?

“Now of course, it is obvious that the future belongs to youth. In very special measure it belongs to these young men, because they have done so much. They must do more. Any man who wins the nation’s highest decoration is marked for leadership. And he must exert it.

“And now, instead of leading in battle, they must lead toward peace. They must make certain that no other young men follow them up to these steps to receive the Medal of Honor. That is the service that the United States would like finally to give to all seven of you as their decoration.

“So, along with our gratitude, with our salute to great soldiers, our affection to you and to your families, goes also our hope that you will be instrumental in bringing about a situation where there will be no more Medals of Honor.”

Bleak would never be comfortable with the acclaim that accompanied the Medal of Honor and the citation. The way Bleak saw it, he was among a multitude of heroes — he just happened to be the one that was “caught” in the act.

“Everyone else was doing it,” said Lois. “He just happened to be seen. He didn’t consider what he was doing was above and beyond. He always played down what he did. Then he’s surprised when it’s noticed.”

It is a tribute to Bleak, the Washington Post observed he “kept mum about his combat record and turned down jobs offered to him by those wanting to do a favor for a war hero.”

He departed eastern Idaho for Dubois, Wyo., about 88 miles east of Jackson where he worked as a rancher and a grocery store meat cutter and truck driver.

“He wanted to go where nobody knew him,” said Bleak’s daughter, Barbara Martin, 68, of Arco.

It was in Dubois where Bleak met Lois, who lived in Idaho Falls but was visiting her parents. The couple married in 1960, returned to eastern Idaho and raised four children. After working at a potato processing plant in Shelley, Bleak joined what is now Idaho National Laboratory and moved the family to Moore, outside Arco, in the mid-1960s, where they operated a 45-head dairy farm. Bleak could not outrun his legend. As a Medal of Honor recipient, he accepted a standing invitation to attend the inaugurations of Presidents John F. Kennedy in 1961 and Richard Nixon in 1969.

He traveled to conventions of fellow Medal of Honor recipients. Bleak had the rare distinction of having a building named in his honor, the Sgt. David B. Bleak Troop Medical Clinic at Fort Sill, Okla., in 1995. It was the first time in a century that any government building had been named for a living American, an act that required approval from the secretary of the Army.

But at home, the Bleaks kept as much of this as possible under wraps.

Occasionally, a colleague corralled the shy Bleak to address a group of Boy Scouts in the early 1970s. He described American citizenship as a two-way street — rights came with responsibilities, something he called “a contract with America.” And Bleak had no patience with “a few loud-voiced extremists who are working toward its overthrow.”

That may well have been the longest public speech Bleak ever delivered. Most of the time, he kept it to a line or two.

“He hated the attention. He was very humble,” said Bruce Bleak.

By no means was David Bleak unique in his modesty. An entire generation of veterans kept their war stories locked up and went about their lives in the decades after World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

Maybe it was survivor’s guilt. Of the 146 Americans who received the Medal of Honor in Korea, 103 were honored posthumously. Nor was Bleak immune to post-traumatic stress. His family said it manifested in a “thousand-yard stare.”

“He said he lived it once,” Barbara Martin said. “It never goes away. A Medal of Honor recipient either pays all at once or throughout the course of his life.”

When Bleak died at the age of 74 in March 2006, his family donated the Medal of Honor and Bleak’s other commendations to the Idaho Military History Museum at Boise, where they are on display.

“He said that it belonged to the people of Idaho,” Bruce Bleak said.

Even among the people who lived among them, the story remained murky.

Angela Keller, a 63-year-old retired certified medical assistant, was living nearby on the family farm when the Bleaks moved to Moore.

As a child, she had an inkling that Bleak was a veteran when he said a few words at a Memorial Day breakfast.

In high school, Keller got the sense that Bleak had received a Purple Heart or some other commendation.

Only after he had died and Keller had moved away from Moore to Idaho Falls had the internet and social media more fully spread the incredible tale of David Bleak.

“I felt honored that I even knew this guy,” Keller said. “He was just cooler than I ever thought. It didn’t make him better because he was already just a good guy. Then you find out that he was a great man who did great things. And I got to know him.”

Korean War Medal of Honorrecipients from Washington and Idaho:

>> WASHINGTON

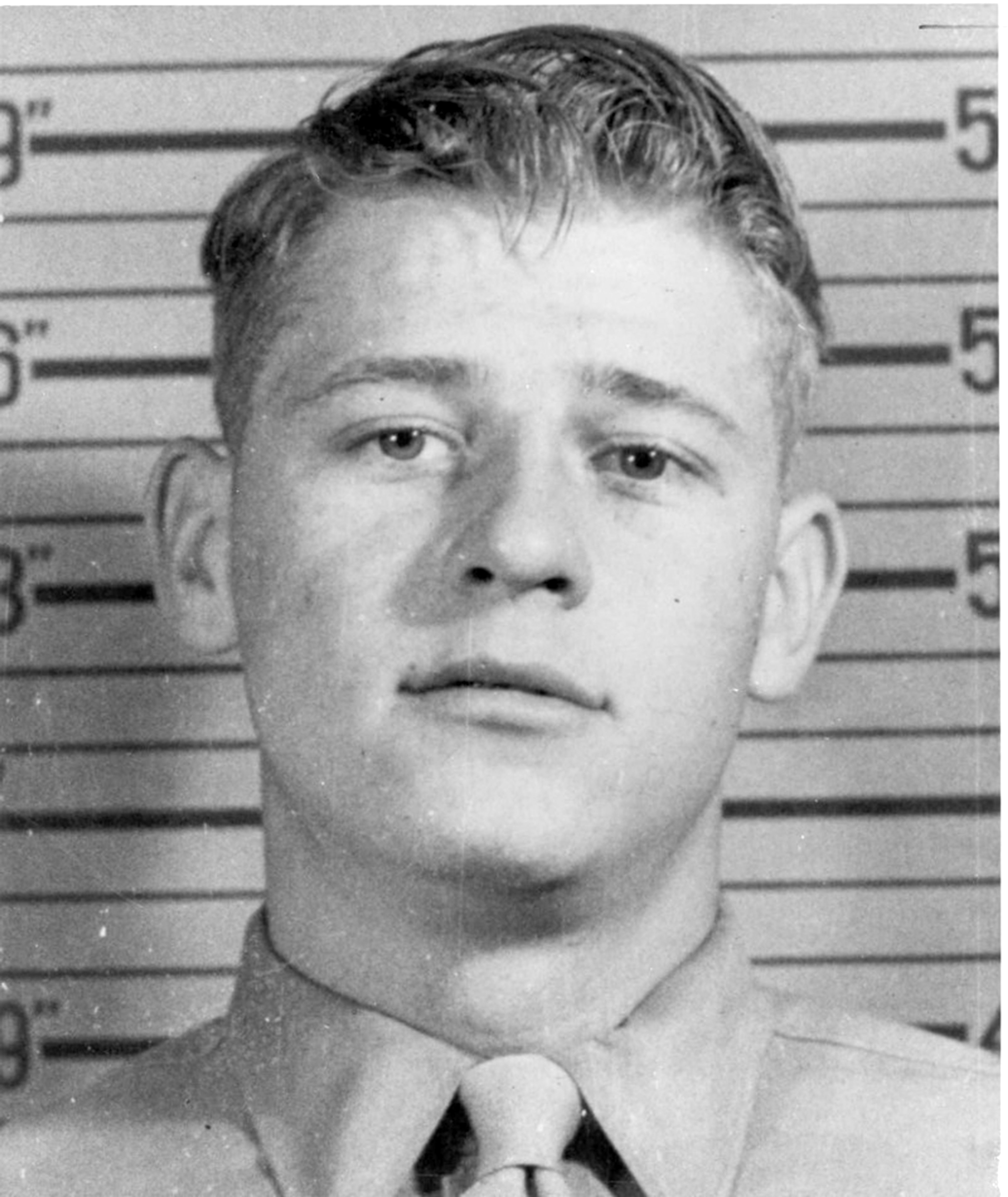

Walter C. Monegan Jr.

Rank: private first class

Branch: Marines

Credited to: Seattle

Born: Dec. 25, 1930

Died: Sept. 20, 1950

Buried: Arlington (Va.) National Cemetery

Action date: Sept. 17, 1950

Location: Near Sosa-Ri, Korea

Citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a rocket gunner attached to Company F, and in action against enemy aggressor forces. Dug in on a hill overlooking the main Seoul highway when six enemy tanks threatened to break through the battalion position during a predawn attack on 17 September, PFC Monegan promptly moved forward with his bazooka, under heavy hostile automatic-weapons fire and engaged the lead tank at a range of less than 50 yards. After scoring a direct hit and killing the sole surviving tankman with his carbine as he came through the escape hatch, he boldly fired two more rounds of ammunition at the oncoming tanks, disorganizing the attack and enabling our tank crews to continue blasting with their 90-mm guns. With his own and an adjacent company’s position threatened by annihilation when an overwhelming enemy tank-infantry force bypassed the area and proceeded toward the battalion command post during the early morning of Sept. 20, he seized his rocket launcher and, in total darkness, charged down the slope of the hill where the tanks had broken through. Quick to act when an illuminating shell lit the area, he scored a direct hit on one of the tanks as hostile rifle and automatic-weapons fire raked the area at close-range. Again exposing himself, he fired another round to destroy a second tank and, as the rear tank turned to retreat, stood upright to fire and was fatally struck down by hostile machine-gun fire when another illuminating shell silhouetted him against the sky. PFC Monegan’s daring initiative, gallant fighting spirit, and courageous devotion to duty were contributing factors in the success of his company in repelling the enemy, and his self-sacrificing efforts throughout sustain and enhance the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Awarded posthumously, Feb. 8, 1952, by Under Secretary of the Navy Francis P. Whitehair to his widow at the Pentagon.

Archie van Winkle

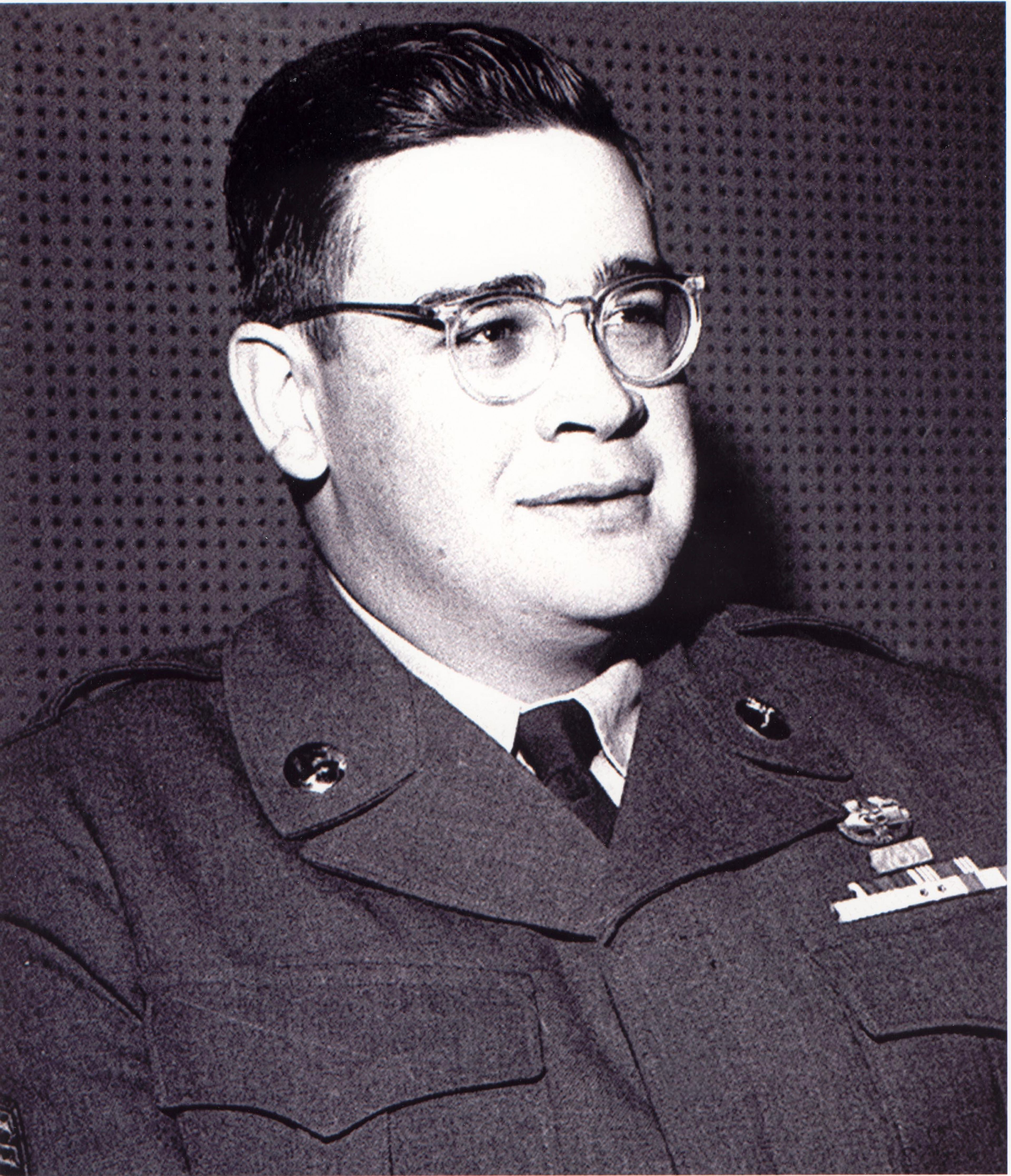

Rank: staff sergeant (highest rank: colonel)

Branch: Marines

Credited to: Snohomish County, Wash.

Born: March 17, 1925

Died: May 20, 1986

Buried: Cremated, ashes scattered at sea

Action date: Nov. 2, 1950

Location: Near Sudong, Korea

Citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a platoon sergeant in Company B, in action against enemy aggressor forces. Immediately rallying the men in his area after a fanatical and numerically superior enemy force penetrated the center of the line under cover of darkness and pinned down the platoon with a devastating barrage of deadly automatic-weapons and grenade fire, Staff Sgt. Van Winkle boldly spearheaded a determined attack through withering fire against hostile frontal positions and, though he and all the others who charged with him were wounded, succeeded in enabling his platoon to gain the fire superiority and the opportunity to reorganize. Realizing that the left-flank squad was isolated from the rest of the unit, he rushed through 40 yards of fierce enemy fire to reunite his troops despite an elbow wound which rendered one of his arms totally useless. Severely wounded a second time when a direct hit in the chest from a hostile hand grenade caused serious and painful wounds, he staunchly refused evacuation and continued to shout orders and words of encouragement to his depleted and battered platoon. Finally carried from his position unconscious from shock and from loss of blood, Staff Sgt. Van Winkle served to inspire all who observed him to heroic efforts in successfully repulsing the enemy attack. His superb leadership, valiant fighting spirit, and unfaltering devotion to duty in the face of heavy odds reflect the highest credit upon himself and the U.S. Naval Service.”

Award presented by President Harry Truman, Feb. 6, 1951, at the White House.

Benjamin F. Wilson

Rank: master sergeant (rank at the time of action; later promoted to 1st lieutenant)

Branch: Army

Credited to: Vashon, Wash.

Born: June 2, 1922

Died: March 1, 1988

Buried : National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), Honolulu, Hawaii

Action date: June 5, 1951

Location: Near Hwach’on-myon, Korea

Citation:

“First Lt. Wilson distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and indomitable courage above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy. Company I was committed to attack and secure commanding terrain stubbornly defended by a numerically superior hostile force emplaced in well-fortified positions. When the spearheading element was pinned down by withering hostile fire, he dashed forward and, firing his rifle and throwing grenades, neutralized the position denying the advance, and killed four enemy soldiers manning submachine guns. After the assault platoon moved up, occupied the position, and a base of fire was established, he led a bayonet attack which reduced the objective and killed approximately 27 hostile soldiers. While friendly forces were consolidating the newly won gain, the enemy launched a counterattack and 1st Lt. Wilson, realizing the imminent threat of being overrun, made a determined lone-man charge, killing seven and wounding two of the enemy, and routing the remainder in disorder. After the position was organized, he led an assault carrying to approximately 15 yards of the final objective, when enemy fire halted the advance. He ordered the platoon to withdraw and, although painfully wounded in this action, remained to provide covering fire. During an ensuing counterattack, the commanding officer and 1st Platoon leader became casualties. Unhesitatingly, 1st Lt. Wilson charged the enemy ranks and fought valiantly, killing three enemy soldiers with his rifle before it was wrested from his hands, and annihilating four others with his entrenching tool. His courageous delaying action enabled his comrades to reorganize and effect an orderly withdrawal. While directing evacuation of the wounded, he suffered a second wound, but elected to remain on the position until assured that all of the men had reached safety. 1st Lt. Wilson’s sustained valor and intrepid actions reflect utmost credit upon himself and uphold the honored traditions of the military service.”

Awarded Sept. 7, 1954, by President Dwight Eisenhower at the Army hospital at Denver, Colo.

>> IDAHO

David Bruce Bleak

Rank: sergeant

Branch: Army

Credited to: Shelley, Idaho/Vashon, Wash.

Born: Feb. 27, 1932

Died: March 26, 2006

Buried: Lost River Cemetery, cremated, no burial

Action date: June 14, 1952

Location: Minari-gol, Korea

Citation:

“Sgt. Bleak, a member of the medical company, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and indomitable courage above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy. As a medical aidman, he volunteered to accompany a reconnaissance patrol committed to engage the enemy and capture a prisoner for interrogation. Forging up the rugged slope of the key terrain, the group was subjected to intense automatic-weapons and small-arms fire and suffered several casualties. After administering to the wounded, he continued to advance with the patrol. Nearing the military crest of the hill, while attempting to cross the fire-swept area to attend the wounded, he came under hostile fire from a small group of the enemy concealed in a trench. Entering the trench he closed with the enemy, killed two with bare hands and a third with his trench knife. Moving from the emplacement, he saw a concussion grenade fall in front of a companion and, quickly shifting his position, shielded the man from the impact of the blast. Later, while ministering to the wounded, he was struck by a hostile bullet but, despite the wound, he undertook to evacuate a wounded comrade. As he moved down the hill with his heavy burden, he was attacked by two enemy soldiers with fixed bayonets. Closing with the aggressors, he grabbed them and smacked their heads together, then carried his helpless comrade down the hill to safety. Sgt. Bleak’s dauntless courage and intrepid actions reflect utmost credit upon himself and are in keeping with the honored traditions of the military service.”

Awarded: Oct. 27, 1953, by President Dwight Eisenhower at the White House.

James E. Johnson

Rank: sergeant

Branch: Marines

Credited to: Washington, D.C.; born Pocatello, Idaho

Born: Jan. 1, 1926

Died: Nov. 2, 1953

Buried: Wall of the missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), Honolulu, Hawaii, and a marker (“In memory”) at Arlington (Va.) National Cemetery

Action date: Dec. 2, 1950

Location: Yudam-ni, Korea

Citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a squad leader in a provisional rifle platoon composed of artillerymen and attached to Company J, in action against enemy aggressor forces. Vastly outnumbered by a well-entrenched and cleverly concealed enemy force wearing the uniforms of friendly troops and attacking his platoon’s open and unconcealed positions, Sgt. Johnson unhesitatingly took charge of his platoon in the absence of the leader and, exhibiting great personal valor in the face of a heavy barrage of hostile fire, coolly proceeded to move about among his men, shouting words of encouragement and inspiration and skillfully directing their fire. Ordered to displace his platoon during the firefight, he immediately placed himself in an extremely hazardous position from which he could provide covering fire for his men. Fully aware that his voluntary action meant either certain death or capture to himself, he courageously continued to provide effective cover for his men and was last observed in a wounded condition single-handedly engaging enemy troops in close hand-grenade and hand-to-hand fighting. By his valiant and inspiring leadership, Sgt. Johnson was directly responsible for the successful completion of the platoon’s displacement and the saving of many lives. His dauntless fighting spirit and unfaltering devotion to duty in the face of terrific odds reflect the highest credit upon himself and the U.S. Naval Service.”

Awarded March 29, 1954, by Secretary of the Navy Robert B. Anderson to his widow.

Herbert A. Littleton

Rank: private first class

Branch: Marines

Credited to: Nampa, Idaho

Born: July 1, 1930

Died: April 22, 1951

Buried: Kohler Lawn Cemetery, Nampa

Action date: April 22, 1951

Location: Chungchon, Korea

Citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a radio operator with an artillery forward observation team of Company C, in action against enemy aggressor forces. Standing watch when a well-concealed and numerically superior enemy force launched a violent night attack from nearby positions against his company, PFC Littleton quickly alerted the forward observation team and immediately moved into an advantageous position to assist in calling down artillery fire on the hostile force. When an enemy hand grenade was thrown into his vantage point shortly after the arrival of the remainder of the team, he unhesitatingly hurled himself on the deadly missile, absorbing its full, shattering impact in his body. By his prompt action and heroic spirit of self-sacrifice, he saved the other members of his team from serious injury or death and enabled them to carry on the vital mission which culminated in the repulse of the hostile attack. His indomitable valor in the face of almost certain death reflects the highest credit upon PFC Littleton and the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Awarded Aug. 19, 1952, by Col. Ernest W. Fry to his parents.

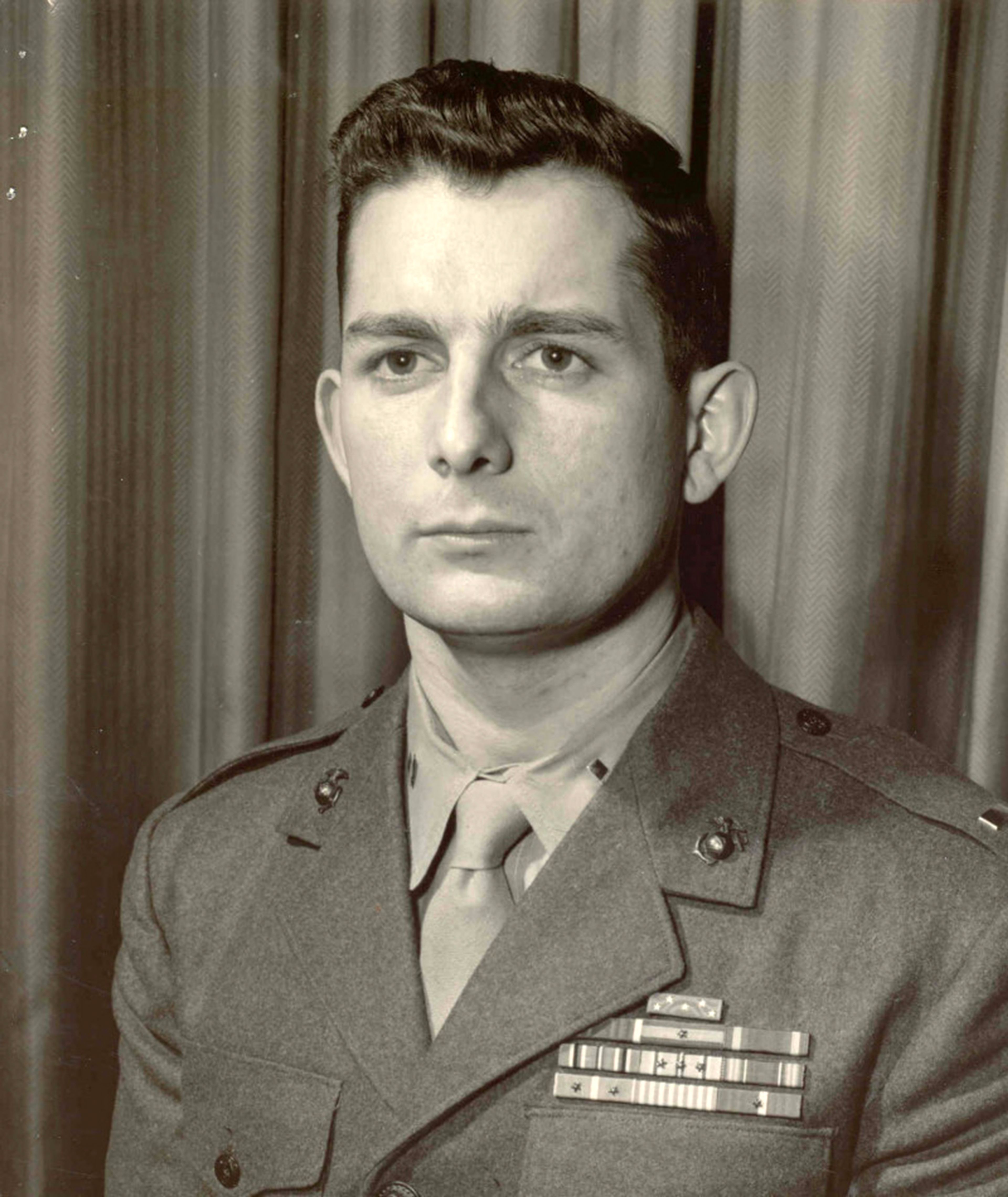

Reginald Rodney Myers

Rank: major (highest rank: colonel).

Branch: Marines

Credited to Boise, Ada County, Idaho

Born: Nov. 26, 1919

Died: Oct. 23, 2005

Buried: Arlington (Va.) National Cemetery

Action Date: Nov. 29, 1950

Location: Near Hagaru-ri, Korea

Citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as executive officer of the 3d Battalion, in action against enemy aggressor forces. Assuming command of a composite unit of Army and Marine service and headquarters elements totaling approximately 250 men, during a critical stage in the vital defense of the strategically important military base at Hagaru-ri, Maj. Myers immediately initiated a determined and aggressive counterattack against a well-entrenched and cleverly concealed enemy force numbering an estimated 4,000. Severely handicapped by a lack of trained personnel and experienced leaders in his valiant efforts to regain maximum ground prior to daylight, he persisted in constantly exposing himself to intense, accurate and sustained hostile fire in order to direct and supervise the employment of his men and to encourage and spur them on in pressing the attack.

Inexorably moving forward up the steep, snow-covered slope with his depleted group in the face of apparently insurmountable odds, he concurrently directed artillery and mortar fire with superb skill and although losing 170 of his men during 14 hours of raging combat in subzero temperature, continued to reorganize his unit and spearhead the attack which resulted in 600 enemy killed and 500 wounded. By his exceptional and valorous leadership throughout, Maj. Myers contributed directly to the success of his unit in restoring the perimeter.

His resolute spirit of self-sacrifice and unfaltering devotion to duty enhance and sustain the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

Awarded Oct. 29, 1951, by President Harry Truman at the White House.

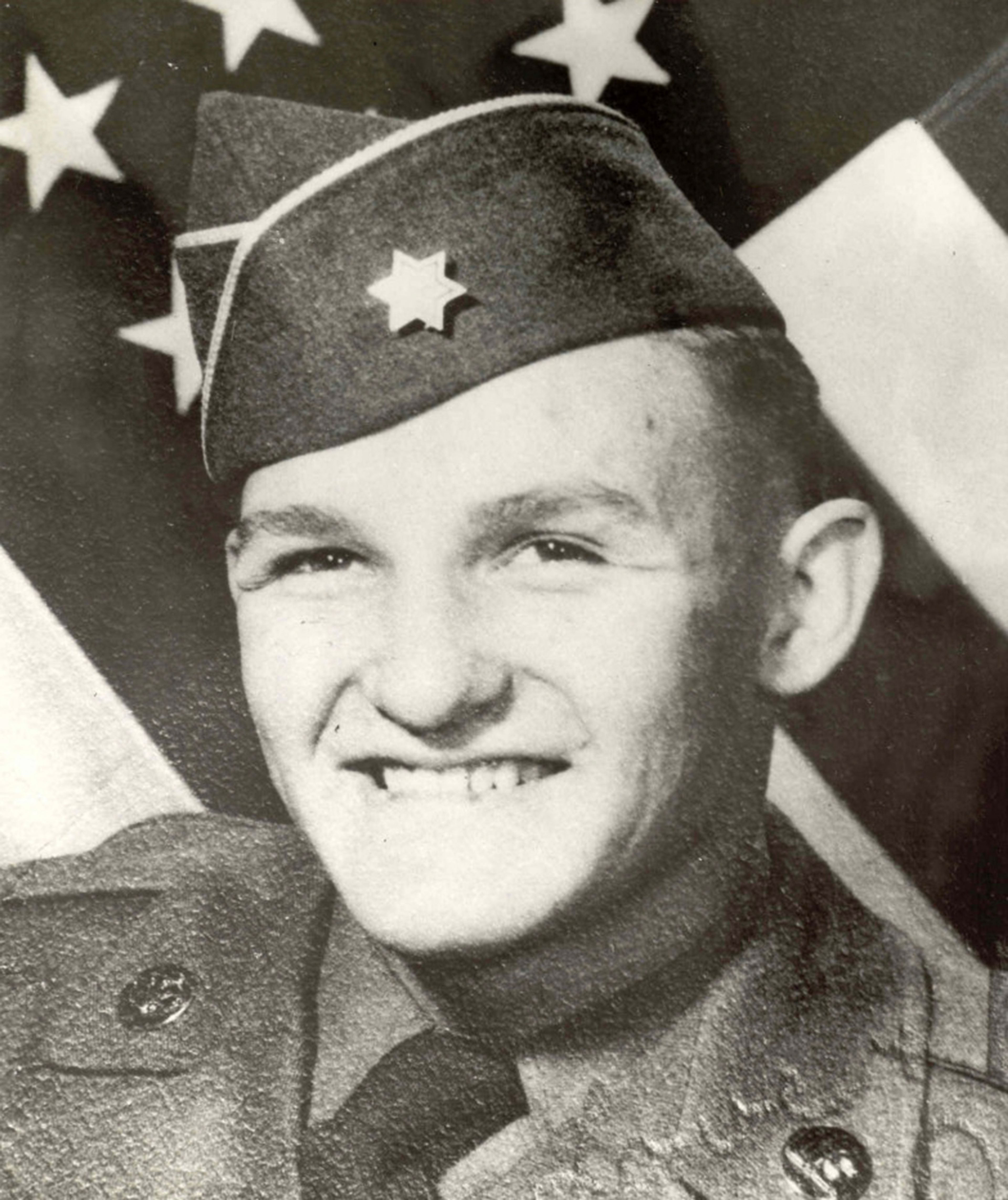

Dan D. Schoonover

Rank: corporal

Branch: Army

Credited to: Boise

Born: Oct. 8, 1933

Died: July 10, 1953

Buried: National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl) Wall of the Missing at Honolulu, Hawaii, and Morris Hill Cemetery, Boise

Action date: July 8, 1953

Location: Pork Chop Hill, near Sokkogae

Citation:

“Cpl. Schoonover distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and outstanding courage above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy. He was in charge of an engineer demolition squad attached to an infantry company which was committed to dislodge the enemy from a vital hill. Realizing that the heavy fighting and intense enemy fire made it impossible to carry out his mission, he voluntarily employed his unit as a rifle squad and, forging up the steep barren slope, participated in the assault on hostile positions. When an artillery round exploded on the roof of an enemy bunker, he courageously ran forward and leaped into the position, killing one hostile infantryman and taking another prisoner. Later in the action, when friendly forces were pinned down by vicious fire from another enemy bunker, he dashed through the hail of fire, hurled grenades in the nearest aperture, then ran to the doorway and emptied his pistol, killing the remainder of the enemy. His brave action neutralized the position and enabled friendly troops to continue their advance to the crest of the hill. When the enemy counterattacked he constantly exposed himself to the heavy bombardment to direct the fire of his men and to call in an effective artillery barrage on hostile forces. Although the company was relieved early the following morning, he voluntarily remained in the area, manned a machine gun for several hours, and subsequently joined another assault on enemy emplacements. When last seen he was operating an automatic rifle with devastating effect until mortally wounded by artillery fire. Cpl. Schoonover’s heroic leadership during two days of heavy fighting, superb personal bravery, and willing self-sacrifice inspired his comrades and saved many lives, reflecting lasting glory upon himself and upholding the honored traditions of the military service.”

Awarded Dec. 2, 1954, by Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens to his mother.