Nashville's Mother Church of Country Music retains its roots as religious house of worship

Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium is known as the Mother Church of Country Music

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium is known as the Mother Church of Country Music. And, indeed, it began as a church, built by a riverboat captain who was converted to religion by an evangelist.

More than 130 years after it was built as the nondenominational Union Gospel Tabernacle, Music City’s most revered concert venue retains its religious roots.

Thousands have filled its original wooden pews surrounded by colorful stained-glass windows to listen to stars ranging from Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton to Prince, Taylor Swift and Elvis, the king of rock ‘n’ roll.

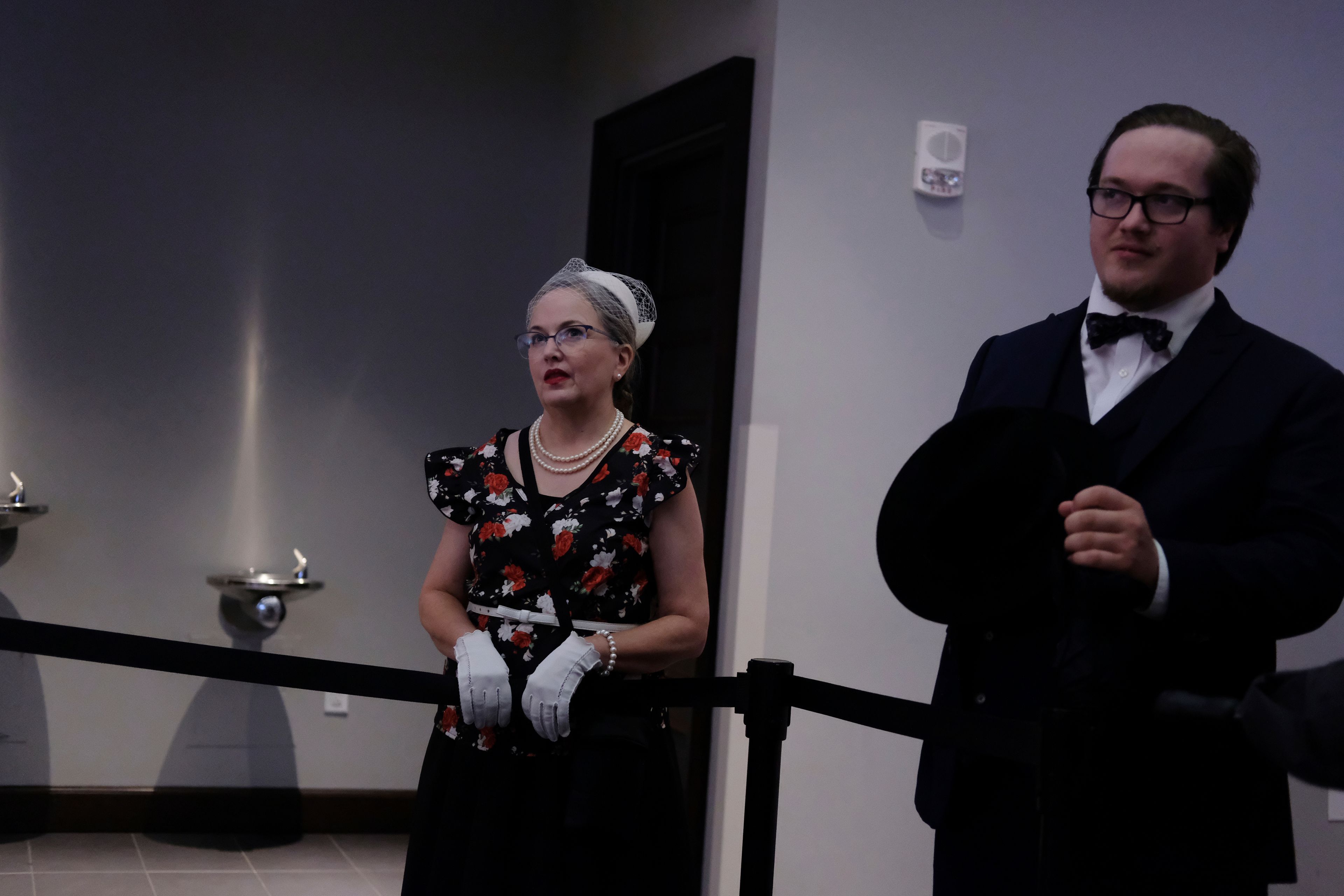

“Technically it’s a building, but it’s clearly a living entity of some sort,” said Jessi Woods, a tourist from Massachusetts. She toured the Ryman’s museum in the morning of a recent visit and attended a performance by the band Postmodern Jukebox in the evening.

It all started with the Rev. Samuel Jones, an evangelist who came from Georgia to Nashville in 1885 for a revival sponsored by local churches under a huge tent.

Jones began denouncing Nashvillians for ignoring what he believed where the sins of the time: everything from baseball and bike riding to prostitution, gambling and dancing. Worst of all for the reformed alcoholic: drinking.

Tom Ryman, a wealthy captain who served whiskey in his steamship line, took offense. So, he rounded up a group of his friends to attend the revival and beat up Jones.

Instead, the story goes that after one sermon, the preacher convinced him to give his life to God.

Ryman stopped selling alcohol on his ships; he wouldn’t even christen steamships with champagne, and instead used jugs of water. He also began to dream about building a house of worship in Nashville for religious gatherings, so evangelists like Jones could have a place to preach.

Through his funding and with the help of donations from the community, the Union Gospel Tabernacle officially opened on May 4, 1892, with a music festival.

The tabernacle did not have a dedicated congregation, said Ryman Auditorium curator Joshua Bronnenberg.

“It was more of a place for, say, like a traveling evangelist to preach in, such as a Billy Sunday or Gypsy Smith or Samuel Jones,” Bronnenberg said.

After Ryman's death, it was renamed after him, and it went on to become revered as one of America’s leading music venues.

“What was built as a religious meeting place for Nashvillians,” the auditorium says on its site, “became a different type of sanctuary that grew bigger than Ryman ever imagined.”

For its first two decades or so, it was a hybrid gathering place hosting religious leaders and some of the biggest names in ballet, opera and theater. It became known as the Carnegie Hall of the South.

“We’ve had all sorts of progressive events: suffrage events, scientific demonstrations, magicians, all kinds of political icons and cultural icons have graced the stage,” Bronnenberg said.

“You also had bizarre things: we’ve had boxing matches, circuses,” he said. “And alongside, we had funerals, we had civil rights protests. … If you had any kind of significant event in the city, it was here.”

It went on to host meetings of the Southern Baptist Convention, memorable performances by big names, such as comedian Charlie Chaplin and magician Harry Houdini, and appearances on stage by President Teddy Roosevelt and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

The venue also became known for its unique acoustics beloved by artists.

“It’s Ryman Auditorium’s roots as a church that resulted in its impressive acoustics,” the Ryman’s site says, “as the auditorium was constructed to project the voices, songs, and instruments of weekly church services.”

It also became the home of the Grand Ole Opry — the most famous country music and entertainment show of its time — from 1943 to 1974.

“The show was transmitted using the world’s tallest radio tower at the time, built just outside of Nashville, bringing country music to living rooms from California to New York for the first time” the site says. “Audiences across the U.S. had discovered a love for country music.”

After the Grand Ole Opry left, the Ryman was vacant for nearly two decades and fell into disrepair. It was restored thanks to donations by artists and members of the community and reopened in the 1990s. It now has a seating capacity of 2,362.

Today, lovers of country music — and other genres — travel to the Ryman from across America and sit on its pews. It's lovingly known as “the Soul of Nashville.”

“It definitely has a soul feel," said Woods, the Massachusetts tourist. "And I don’t believe it’s just because of the musical acts that have been there, but there’s a palpable energy, for sure.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.