Cave of wonders

Wasden collection of ancient bones stirs renewed interest in bison hunting grounds near Idaho Falls

By most estimates it was a blood bath.

Our story begins 9,000 or 10,000 years ago about 20 miles west of Idaho Falls. A group of native people lined up barriers to funnel bison into the sharp drop off of a collapsed lava tube cave. Then they chased the bison into the trap. About 60 hapless creatures stampeded into the hole and were speared and butchered.

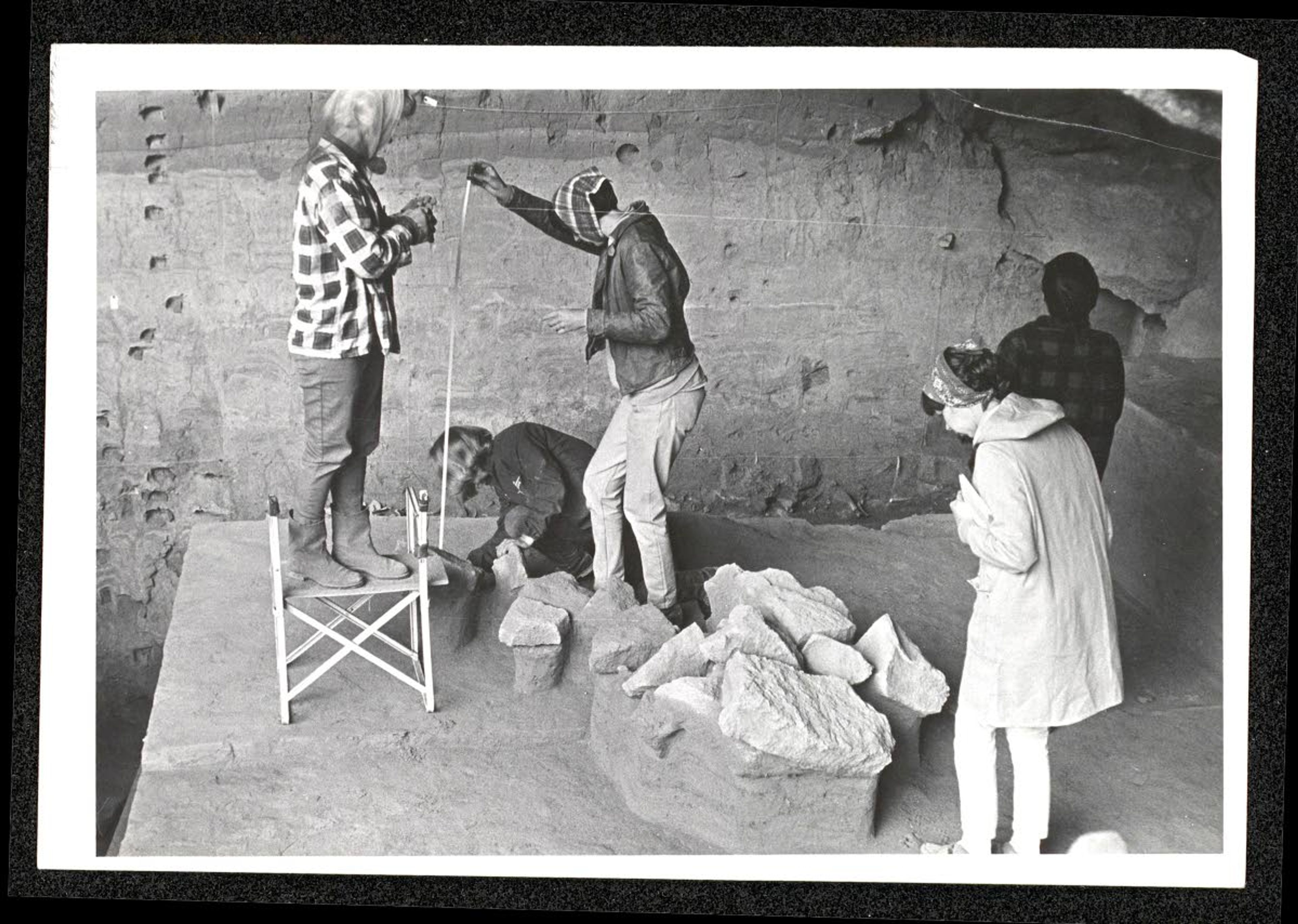

Fast forward several thousand years to 1965. A group of amateur archaeologists called the Upper Snake River Prehistoric Society became interested in three lava tube caves about 20 miles west of Idaho Falls.

One in particular, Owl Cave on land owned by Leonard Wasden, showed promise. With the help of a professional archaeologist B. Robert Butler of the Idaho State College Museum in Pocatello, they began excavations. Excavations continued into the 1970s with other teams from Idaho State University and the Upper Snake River Prehistoric Society.

What the diggers found was incredible. Besides prehistoric bison remains, researchers found bones of mammoths, camel, dire wolf and lion, all with the presence of human tools and even pottery. Evidence suggests that mammoths may have been around longer on this side of the Rocky Mountains than on the east side. Initial research has placed mammoth DNA on the cutting edges of knives and spear points.

The collection was boxed up and sent to the ISU museum. Where it sat, for the most part.

‘A huge story to tell’

“There’s over 80,000 pieces to this collection. It’s huge,” said Carrie Athay director of curation and collections at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Athay said the original agreement with ISU was that anything that came out of the ground was the property of the Wasden family. It was the wishes of the family to have the collection properly curated and available for legitimate researchers to study, but that wasn’t happening at ISU. The Wasden family requested the collection be brought up to the Idaho Falls museum and made available for proper curation and cataloging. But ISU balked at releasing the collection. Eventually, the Wasden family pulled out their trump card, a written agreement from the 1960s stating they owned the collection.

“(The Wasden family) really felt like this was a collection that had a huge story to tell,” Athay said. “They wanted to make sure that that story could be told. We were really lucky to be able to work with the family and to be bring the collection here.”

Several truckloads and at least three days of driving back and forth between Idaho Falls and Pocatello brought the huge collection to the Museum of Idaho a few years ago. But they had a problem: Where to house it?

“When we brought it to the Museum of Idaho we didn’t have space,” Athay said. “We were in the middle of our expansion and we didn’t really know where were going to put this collection.”

Remodeling work was done on the museum’s annex building and a $172,000 Save America’s Treasures grant was applied for to buy a proper storage system and hire a curator, Kristina Frandson.

Today, Frandson splits her workdays between cataloging at a computer and getting 10,000-year-old dust on her protective gloves from ancient bones and spear points. She expects to work with the collection for nearly two years.

“Everything is in bankers’ boxes,” Frandson said. “My job is to go through these bankers’ boxes and create a catalog of what we have and what maybe missing for the time being in the boxes that I haven’t gotten to yet. My main job is to put everything back into its context from the excavation. What happened is they stored the bones previously by type, which is amazing for some kind of research — in case you want to look at only tibias you can go to the cabinet and look at only tibias — but the issue with that is that it takes the bones out of what unit they were from and what level within the unit they were from and what layer.”

Once cataloged, pieces from the collection are stored in waterproof cabinets with stacks of sliding drawers, some only inches deep.

“I’m trying to make it so that the bones from one unit are within one cabinet and then researchers can come in and find the bones in the unit they need to be,” Frandson said.

Generating new interest

Word is getting out to archaeologists and paleontologists in academic circles about the Wasden collection and researchers have been making requests to study the collection with various questions in mind.

Athay said a committee consisting of representatives of the Wasden family, the museum and Idaho National Laboratory archaeologist Suzann Henrikson reviews research requests to make sure they “are legit.”

“As my career progressed, the one thing that I noticed in the literature is that the Wasden site was disappearing,” Henrikson said in a video documentary produced by Harris Media School. “It was just not being mentioned by archaeological researchers. I thought that was an incredible shame. This is an amazing site. It was underpublished and there was never a final report prepared for people to go to and site. … I decided that I was going to put forth a concerted effort to try and get the Wasden site back in the publications.”

Further study of the collection is important because advances in science could help researchers develop a more accurate timeline for some of the finds. More recent studies of some of the bison bones found in Owl Cave date back to more than 14,000 years ago.

A 2017 report for the Society for American Archaeology that Henrikson co-authored with four other researchers said, “While Owl Cave may be one of the most important terminal Pleistocene archaeological sites in western North America, its research potential has yet to be realized.”

Randall Harris, the grandson of Leonard Wasden, also hopes the collection’s new accommodations will further study.

“I’m really grateful that we were able to come together and accomplish an important link in this chain of events that brought Wasden cave artifacts back to the public’s attention and be able to place them in an environment that truly has the same passion that we felt toward these items and why that places (the) Idaho Falls area on the map,” Harris said in the Harris Media School documentary.

“The cool thing is that since the collection has come here, we have had constant research proposals and we have had constant interest in this collection and interest in really trying to understand this early time frame of Idaho,” Athay said. “What’s going on here at the end of the Ice Age?... Things that we’re looking for are what your question is and what you’re trying to answer with this collection.”

Missing pieces

The Wasden cave collection does offer several mysteries and questions. One is where are all the bison heads?

“We don’t have a lot of cranial pieces, not a lot of heads and horn cores and that’s a little bit why we don’t know exactly what specimens are there,” Athay said. “That is the question, what are they doing with the cranial parts?”

Without the heads of the bison, researchers have a more difficult time figuring out what species of ancient bison they’re looking at. It’s assumed that the heads were carried away for ceremonial purposes or to be placed on the mantel back home.

Another question is how and why was a large portion of a mammoth found in a section of cave too small for a mammoth to fit in?

“The stone tools that they found with the mammoth don’t match up time frame wise,” Athay said. “Those stone tools are more of a Folsom time period, which is more closely associated with the bison drive time frame and a little bit later. The mammoth is usually associated with bigger stone tools like projectile points. We have elephant DNA on some of these Folsom points. It shows us that these were used to process the mammoth.”

Athay said some of the collection is being incorporated in the museum’s “Way Out West” exhibit, which features a replica of a towering mammoth.

After the Wasden collection has been properly curated, Athay said the cave sites could see more excavations.

“We’ve looked at aerial views of it,” Athay said. “From above, you can still kind of see ancient drive lines where they might have driven these bison. There’s potential that they were driving (bison) into two caves that are right there, but only one cave has been excavated. We don’t really know what’s going on in this other cave.”

For more information on the Wasden collection, search “Wasden Cave Archeological Documentary” on YouTube.

Painter may be contacted at jpainter@postregister.com.