Blackfoot bison hunt goes bad

Montana singer and his group run afoul of tribal authority in Gardiner standoff

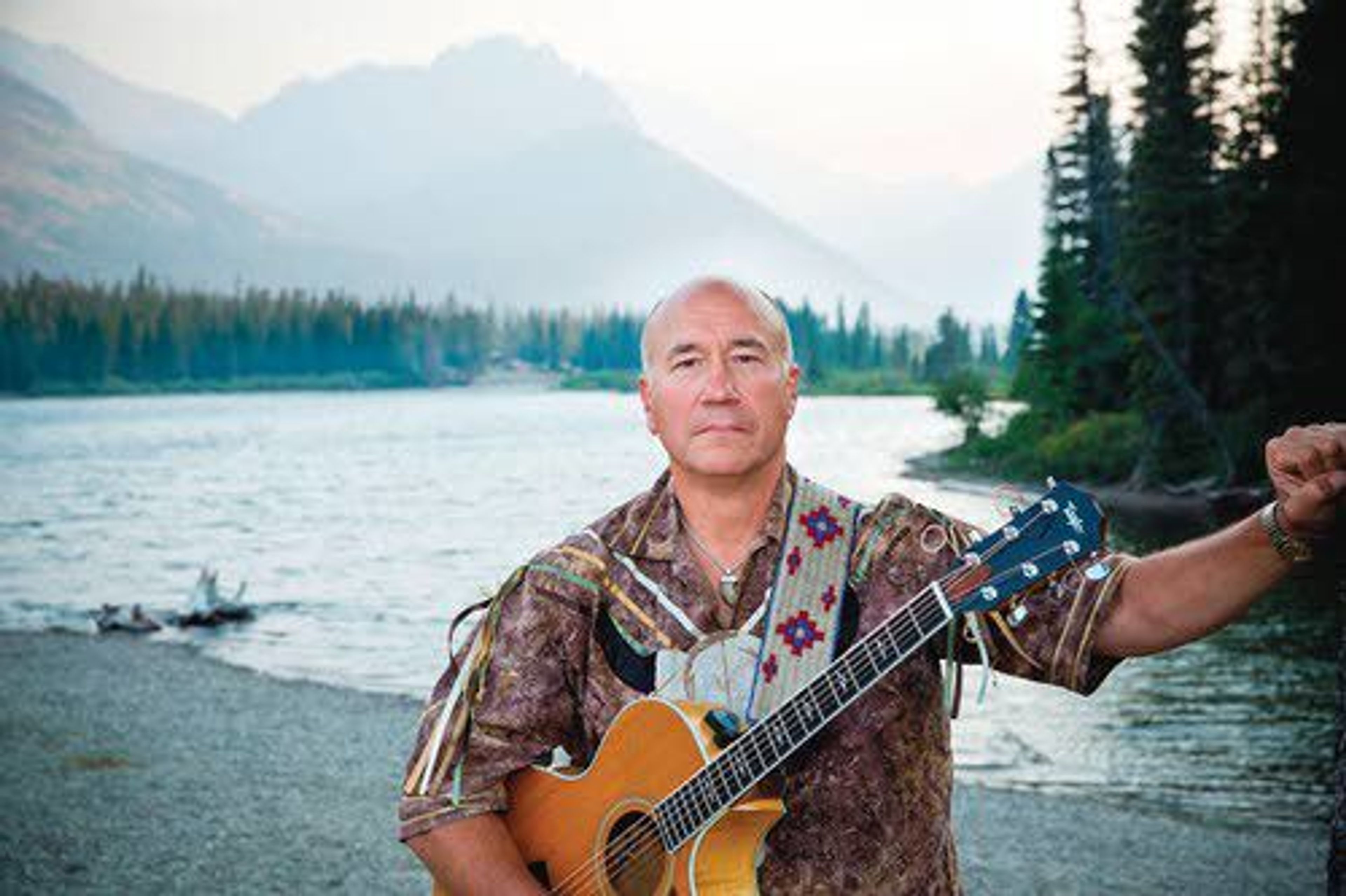

Jack Gladstone's first hunt may be his last.

The well-known Montana singer, who has received the 2016 Governor's Arts Award along with other honors and touts the nickname "Montana's troubadour," is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe. As such, he secured one of the first tribal permits to hunt bison near the Yellowstone National Park boundary earlier this month. This is the first year the tribe has exercised its treaty rights to hunt Yellowstone bison when they migrate into Montana near Gardiner and West Yellowstone.

But after tangling with the tribe's game wardens, Gladstone would be happy never to hunt again.

"Because I'm a tribal member they have the authority to make my life unbearable on the reservation," he said. "I'm very, very troubled."

Blackfeet tribal attorney Derek Kline did not respond to a phone call to his office.

Gardiner hunt

Few bison were migrating out of Yellowstone when Gladstone arrived in Gardiner on Feb. 7 with his wife, Patti, son-in-law Tyrel Hulet, and his friend Sam Miller. The extra folks were there to help Gladstone butcher and haul a bison if he was lucky enough to shoot and kill one of the large animals.

But the scene near the park boundary was offensive to veteran hunters Hulet and Miller. Tribal members sat in their trucks until bison wandered out of the park far enough to legally shoot. Some of the animals were injured and ran back into the park.

"It wasn't what I expected for a hunt," said Hulet, a Columbia Falls resident.

"That was troublesome," Gladstone agreed.

"It was pretty wild," said Miller, a Kila resident. "The dynamics were strange."

The firing line, as some people refer to it, is a constant source of complaints to the Park County Sheriff's Office.

"There are a lot of state and tribal hunters congested in a small area," said Sheriff Scott Hamilton of the Beatty Gulch region just outside the park boundary. "People block the road with their vehicles. And some locals are upset with the way the bison are taken. There are a lot of shots, not all of them clean shots. It's difficult for people to watch that."

Elk instead

While at Beatty Gulch, one of the Blackfeet game wardens, three or four of whom journeyed to the area to monitor their tribal hunters, spread the word that the bison tag could also be used to take an elk. One of Gladstone's friends shot a spike bull on Feb. 9 above Gardiner off Travertine Road. Wardens arrived, checked the hunter's license and there was no problem.

"The next morning I had elk fever," Gladstone said after helping his friend.

So he and his crew returned to the area to see if Gladstone could find an elk. Because Hulet and Miller had been warned that they couldn't be near Gladstone when he shot, they all stayed in the truck while Gladstone stalked a cow elk about 250 yards from the end of the road. He shot, the elk died, and his family and friends walked over to help gut and haul the animal back to the truck.

A Blackfeet tribal warden showed up when the group was almost done. He told them to move the gut pile farther away from the road. They complied, loaded the elk into the back of Hulet's Ford F-250 diesel and tried to drive away but were flagged down by wardens.

That's when chief game warden Keith Lame Bear showed up. When contacted by phone on Tuesday, Lame Bear said he was too busy delivering emergency rations to outlying tribal members to discuss the incident.

Citations, accusations

"He accused us of hunting," Hulet said. "We tried to tell him we were there just to help (Gladstone) get it out of the woods. He said, 'You have blood on your hands. You've been hunting.'"

Gladstone's crew countered that other people were being allowed to help tribal hunters with their bison, including a group of nontribal members who spend part of the winter near Beatty Gulch, and they weren't being cited.

"There were a lot of other people running around doing the same thing," Miller said. "I definitely felt like it was pretty personal."

Hulet said at first that Lame Bear asked if they had enough cash to pay the $500 fine for unauthorized hunting. Hulet told him they didn't carry that kind of money. Then the fine was raised to $12,000 for Hulet and Miller. As collateral for the fine, the wardens ordered the truck towed and impounded, the rifle and elk confiscated. Gladstone was charged with providing false information to a game warden for saying Hulet and Miller weren't hunting with him.

"I was kind of dumbfounded," Miller said. "It was almost like a ransom situation.

"It felt like I didn't have any rights at that moment."

Standoff

As the argument heated up over whether the tribal wardens had authority over nontribal members off the reservation, a Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks warden arrived. He called the Park County Sheriff's deputy, who then called the sheriff.

"I've never been faced with that situation before," Sheriff Hamilton said.

So he called the state attorney general's office. Deputy attorney general Melissa Schlichting told him if the truck had been used in the commission of a crime, it could be seized. She later learned that advice was incorrect.

"We were operating under the idea that there was an agreement between the tribe; Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks; and Yellowstone National Park," she said. "But I was uninformed."

After reviewing the situation the next Monday, she said no tribal game wardens have authority to seize property or even cite nontribal members for any civil infraction off the reservation.

"They can only cite tribal members for violations of their code," Schlichting said.

"It's really confusing, hence why we were caught flat-footed, not knowing what applied and did not apply," she added.

Sheriff Hamilton was uncomfortable with the situation, just one of several problems and complaints surrounding bison hunting near Gardiner that his office has to deal with every winter.

"My agency expends a lot of overtime and resources down there," he said.

The standoff in the streets of Gardiner left Gladstone angry and ashamed.

"It was a very confusing time for the county sheriff and state game wardens," Gladstone said. "I felt a degree of shame for the optics, they were horrible."

Negotiations

Luckily for Gladstone's group, he had driven to Gardiner, as well, so they had a car to return home in. But the fight was not over. He appealed the fines and impoundment to the Blackfeet Nation Fish and Wildlife, aided by his attorney.

"My desire is to straighten out this approach because this looks like hell," Gladstone said. "It's the only way to force change."

After long negotiations with tribal officials, they agreed to drop Hulet's and Miller's fines and return the truck and rifle, but not the elk. Gladstone is also prevented from hunting bison for a year.

"I say thank you," he said, because his first - and possibly only - hunting trip turned out so badly he's in no hurry to repeat the experience.

Gladstone agreed to talk about the situation because he fears that the way the Blackfeet Tribe is now conducting its bison hunt is unsustainable.

Sheriff Hamilton agreed that the hunt - which also involves other treaty right tribes in addition to tribes that are awarded two state bison tags - is getting congested. Montana recognizes the treaty hunting rights of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, the Nez Perce Tribe, Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, and the Confederated Tribes of the Yakama Nation.

"Calls actually picked up about a week ago when the Blackfeet showed up," Hamilton said. "They came in with a large number of hunters, took 40 or 50 bison" in a couple of days "and didn't coordinate with the other tribes. So they ruffled some feathers."

Last Sunday, more than a week after the truck was confiscated, Hulet got his pickup back from Gardiner. The tow fee was $455. Gladstone also paid a $350 fine to the Blackfeet Nation Fish and Game. With attorney fees, the final cost of not getting an elk was close to $5,000.

"This was quite the ordeal," Hulet said.

"It was a crazy situation," Miller said. "It didn't feel like anything American."

Gladstone apologized for his part in the "misunderstanding."

"Nothing like this is ever going to happen again if I have anything to say about it," he said.