‘Airbnb for outdoors’ comes to Idaho

LandTrust.com is backed — and used — by billionaire Wilks brothers

A website that has been described as “Airbnb for outdoor recreation” is being backed by two Texas billionaire brothers who’ve drawn criticism in Idaho after discontinuing public access on roads that cross their properties. Now they’re offering entry to some of those properties through the site — for a fee.

LandTrust.com, which was founded in 2019, promises to connect outdoor recreationists with private landowners, most often for hunting or fishing but also for activities like hiking, bird watching and more. The Montana-based business allows owners to list their properties and name their price for various hobbies.

LandTrust founder and CEO Nic De Castro told the Idaho Statesman in an email the service is a win-win for outdoor enthusiasts and landowners, the majority of whom De Castro said are “owner/operator, multigenerational farms and ranches.”

The idea has drawn concern from some outdoor recreation experts, especially over its affiliation with Dan and Farris Wilks, the Cisco, Texas, oil tycoons who gated off roads across their properties. But LandTrust has also garnered support over its potential to benefit struggling farmers and ranchers.

Wilks brothers list access to Idaho properties

According to financial news site FinSMEs, the Wilks brothers led a $6 million Series A funding round, a fundraising effort in which stock is issued to investors, earlier this year. The website reported LandTrust planned to use the funds to expand into five more states. Currently, it partners with landowners in more than a dozen states, primarily in the Midwest, Intermountain West and South.

The Wilks brothers, who earned billions selling a fracking company, gained prominence in Idaho and Montana in the late 2010s after buying tens of thousands of acres across several properties, including 38,000 acres on the remote Joseph Plains west of Grangeville. In multiple instances, they erected gates at their property boundaries to block access on roads that had long been used by the public — and which some critics say are public rights-of-way that were illegally blocked off.

The Wilks brothers also backed a controversial 2018 law that hiked penalties for trespassing on private property.

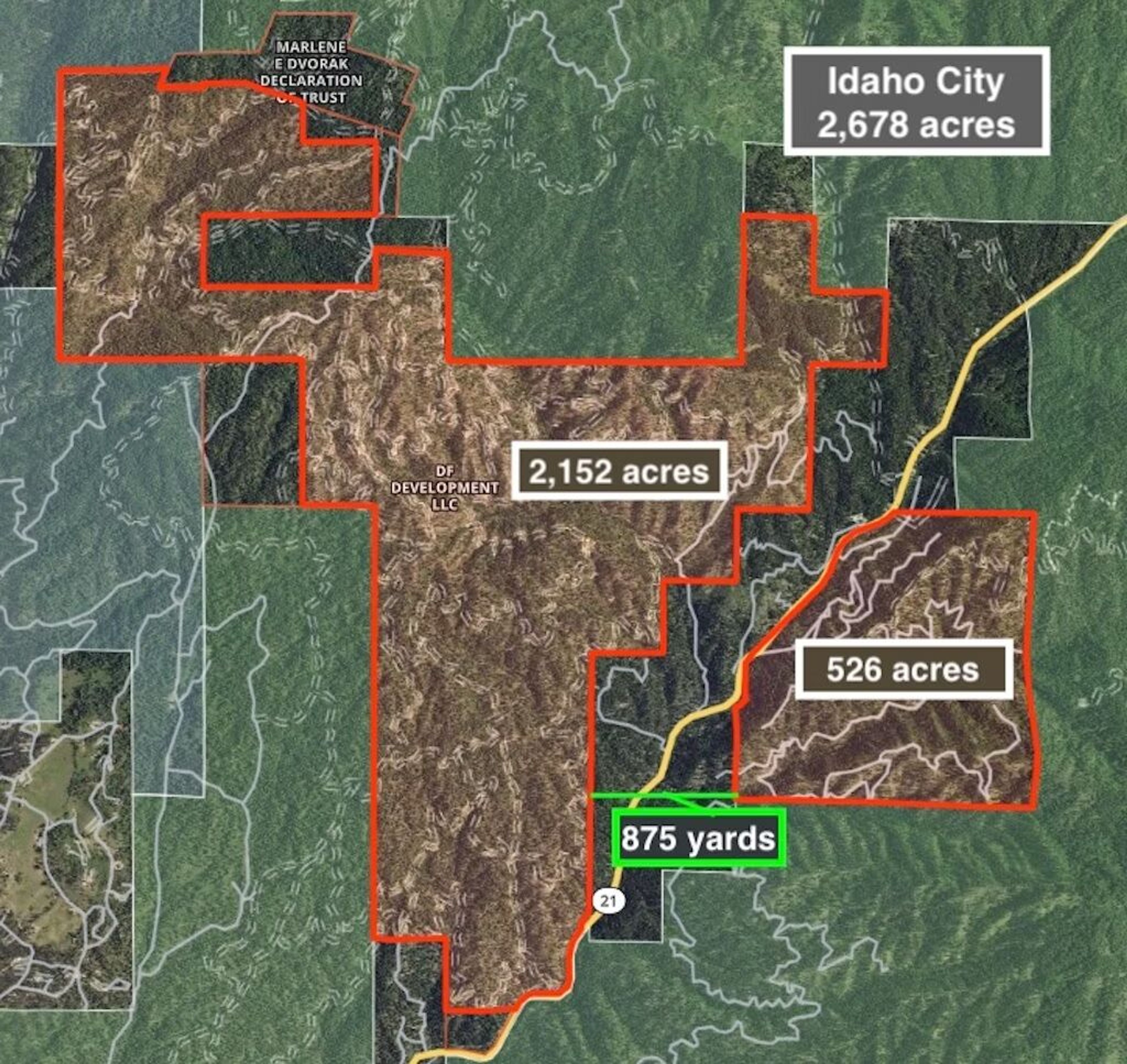

Now Idaho residents can access some of their properties through LandTrust. Three properties are listed on the site under the name “DF D” — referencing DF Development, the name of one of the brothers’ businesses. Two of the properties are near Idaho City, and the other is near New Meadows. All of the listings say they are new additions to the site.

Booking the sites could cost as much as $4,300 for five days of self-guided hunting or $4,500 for bear hunting with a guide, according to the listings. Other activities include shed hunting for around $100 per day, bird watching and wildlife photography for $82 per guest per day, or $35 per guest per day for “outdoor recreation.”

The Wilks’ listings make up a combined 8,600 acres — about 70% of the 12,000 acres De Castro said LandTrust lists in Idaho.

Though the brothers drew the ire of many Idaho hunters in years past, De Castro said he has no reservations about working with the pair.

“Yes, the Wilks (brothers) are very large private landowners, but we treat them just like any other landowner who chooses to facilitate controlled recreation access to their land through LandTrust,” De Castro told the Idaho Statesman. “If you believe in property rights, why should they be treated any differently?

“As far as reputation, we have multigenerational landowners who’ve bordered Wilks properties for years and have said that they’re good neighbors,” he added. “Their opinion carries weight with us.”

Wildlife advocates worry over privatization

Brian Brooks, the executive director of the Idaho Wildlife Federation who spoke out against the Wilkses’ road closures, said he doesn’t believe LandTrust is anything to be up in arms about.

But he is concerned about its ties to the Texas brothers.

“The first thing that comes to my mind as a representative for hunters and anglers is that we need to keep in mind that these are the same people funding legislators and funding an anti-public lands movement (in Montana),” Brooks told the Statesman in a phone interview.

Brooks said there’s nothing wrong with landowners charging people to hunt on their property, though he noted that it could start to exclude Idahoans who aren’t able to pay. Still, those people would have the option of recreating on public land.

By law, wildlife in Idaho is considered property of the state — public property. But some outdoor enthusiasts worry that Montana, Utah and some other states are moving toward privatization of wild animals, Brooks said.

Last year, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks gave Dan Wilks several permits to hunt trophy elk at his N Bar Ranch in what is typically a special permit elk hunt area with slim chances of drawing a tag. Outdoor Life reported that, in exchange, Wilks allowed several Montana hunters to access the 179,000-acre ranch to fill their own tags.

Brooks said a service like LandTrust could be further incentive for Idaho to move away from managing wildlife — and therefore hunting — as a public resource.

“Right now, hunting is incredibly egalitarian,” Brooks said. “A billionaire has every chance to draw a tag and get a mule deer as some 16-year-old in high school.”

Brooks also said he worries LandTrust listings will compete with existing methods through which hunters access private land. In some cases, hunters simply ask private landowners to hunt on their property, and the property owner typically has no financial gain.

Hunters can also access private parcels that are part of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s Access Yes and Large Tracts programs, which are funded through hunter and angler dollars. Both programs compensate landowners, but Brooks said rates aren’t exactly competitive. Landowners may find listing their property on LandTrust is far more lucrative.

“All they have to do is outbid Fish and Game, and that’s not hard to do for a wealthy person,” he said. “We’re going to see it escalate and, depending on the landowner, I think the average sportsperson is going to be outbid.”

Aaron Lieberman, executive director of Idaho Outfitters and Guides Association, said he’s not worried about competition with licensed outfitters. Lieberman said little outfitting happens on private land to begin with, and he noted LandTrust listings could force property owners to take on a lot of administrative work that outfitters handle. That can include greeting clients, showing them which areas of land they can use and, perhaps the most challenging, securing insurance in the event that someone is hurt.

Lieberman said the insurance market for outfitting is difficult and rarely offers businesses full coverage. He said he would anticipate similar issues for homeowners listing their land online.

Like Brooks, he said he fears LandTrust could be one step toward “informal commercialization of wildlife and game management.”

De Castro, LandTrust’s founder, told the Statesman he hasn’t heard any concerns about the website competing with Fish and Game programs or outfitting businesses. According to Montana Free Press, at least one property owner using LandTrust previously granted access through Montana’s equivalent access program.

De Castro said LandTrust stands for private property rights.

“(We believe) a landowner should be able to choose whatever type of access to their land that suits them, whether that’s no access, allowing open public access, leasing to outfitters, enrolling in a state-run paid access program like Access Yes, or facilitating access through a platform like LandTrust,” he said in an email. “If you believe in property rights, as we do, you should support any of those choices with the same enthusiasm because they’re exercising their rights.”

LandTrust could revive struggling properties

Plenty of landowners are exercising the right to choose LandTrust for access to their properties. The company’s website says it has more than 1 million acres of private land for paying customers to explore, and it touts the private hunting experience as a way to take pressure off public lands while bolstering farms and ranches.

“As people who love the outdoors ourselves, we believe it’s an amazing opportunity for us to be able to access private lands that weren’t previously publicly accessible to pursue our outdoor passions while financially supporting these families who steward them,” De Castro told the Statesman.

Tom Page, an Idaho landowner who’s on the board of the Idaho Wildlife Federation and the Western Landowners Alliance, said listing access on LandTrust could be a lifesaver for some Idaho families.

Page said private properties that are large and undeveloped enough to create wildlife habitat worth hunting need new ways to sustain themselves.

“If we can find a way where the landowner doesn’t have to do a ton more work and then can generate some income, I don’t see that that’s so bad,” Page told the Statesman in a phone interview.

Page said the alternative could be dividing or developing the land, resulting in habitat loss. While he said he doesn’t intend to list his land, which is in Custer and Lemhi counties, on LandTrust, he understands the appeal. Page said it’s part of the changing landscape of hunting.

“I think the era of free or low-cost hunting is going away,” he said.