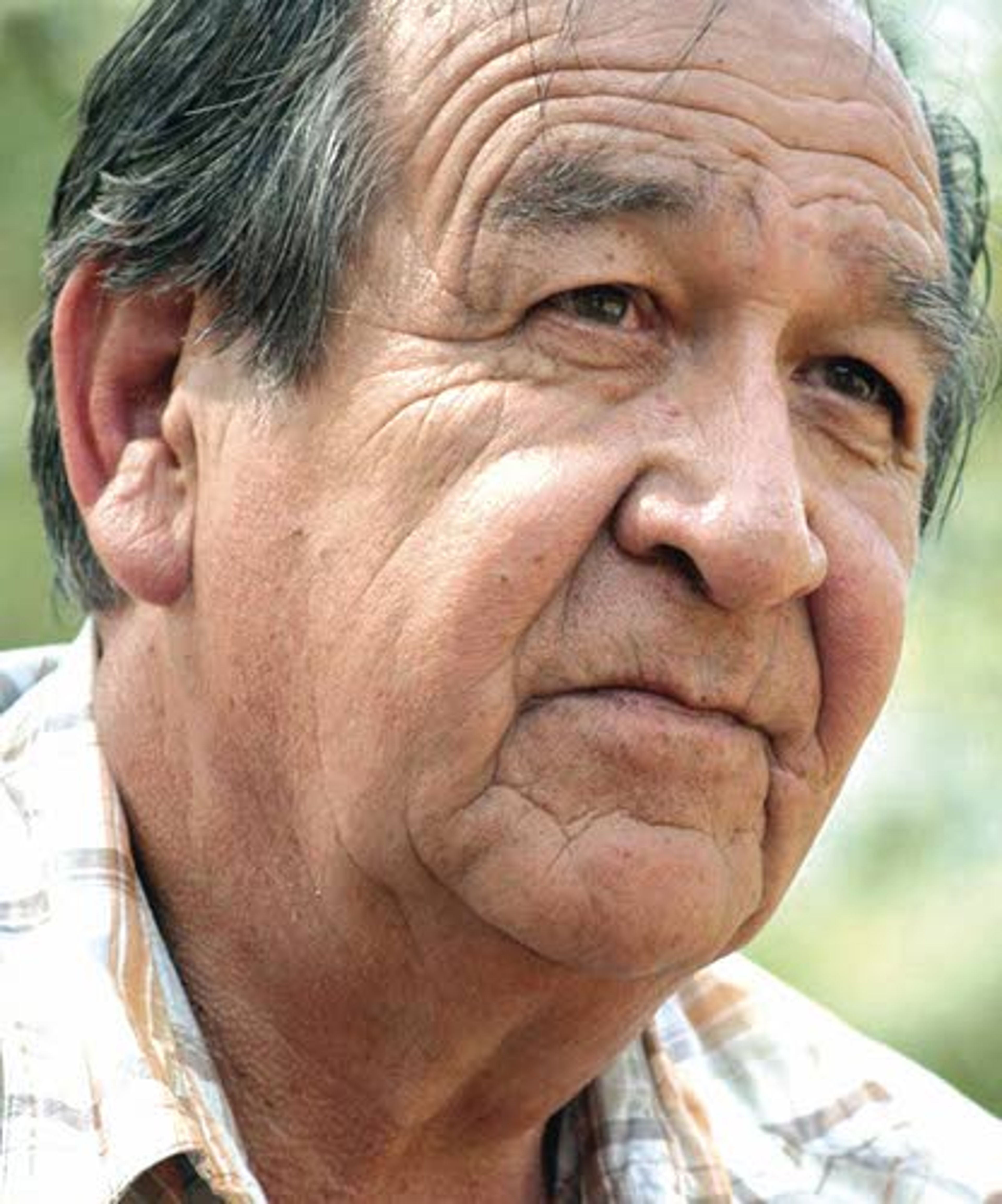

On July 26, 2013, Elmer Crow Jr. perished in the process of rescuing two of his grandsons from the Snake River at Buffalo Eddy. He died saving those he loved, at a place that he loved and in a river he loved.

Elmer was born March 24, 1944, in Orofino, to Elmer Crow Sr. and Hattie Joy. His blind grandmother Edna Miller took the responsibility of raising Elmer and instilling in him the traditions and culture of the Nez Perce and Cayuse tribes. Under her care, Elmer was taught by numerous tribal elders, including five who had fought in the Nez Perce War. From them, he learned the Nez Perce language, traditional hunting and gathering sites, a love for the land and techniques for constructing traditional tools and hunting and fishing gear. He was taught traditional and modern hunting and fishing techniques by his father and extended family, and he regularly harvested salmon throughout the Nez Perce usual and accustomed fishing areas from central Idaho to the now-inundated Celilo Falls. The full extent of the wealth of traditional Nez Perce knowledge and culture that was lost with his passing will never be known.

Elmer spent several years in the Slickpoo Catholic Mission School and also attended Orofino and Lapwai schools. He was held back in the first grade because his English was poor, having been raised in a household that spoke only Nez Perce. Throughout his youth, he learned to live with intense racial discrimination and injustices that were common to American Indians at the time. Often, he defended the underdog, the picked-on and the rejected. He accepted that he could not merely be as good as a white man, but had to be better to earn the same amount of respect.

When he was 17, underage for service and weighing only 124 pounds, his father gave permission for him to enlist in the U.S. Army, where he served in the 101st Airborne Division based out of Elmendorf Air Base in Alaska. Upon his honorable discharge, Elmer graduated from the Operating Engineer School at Weiser and returned to Orofino, where he worked on the construction of Dworshak Dam. Here, Elmer met Lynda Worthen and her family. Lynda's parents Hal and Beula became surrogate parents to Elmer, and he always considered Beula his chosen mother. Elmer and Lynda married on April 11, 1970, and honeymooned, appropriately enough, with a salmon fishing trip up the Lochsa River. Over the course of the next 10 years, the couple was blessed with three sons and a daughter. They moved throughout Idaho following construction jobs and camping, fishing, and generally enjoying the natural wonder of Idaho. In one stretch between jobs, Elmer, Lynda and their first two boys lived off the land for four months throughout Nez Perce Country from the Blue Mountains to the South Fork of the Salmon River. They moved to Gillette, Wyo., with the rest of Lynda's family in 1977, but his beloved homeland drew him back to Idaho just three years later, and he lived on the family homestead near Lapwai for the rest of his life. He treasured most the time he spent with his family and fishing. He was a fixture at his kids' sporting, scouting, 4-H, and school events, and he got to the river to fish as often as he could.

Elmer's dedication to the natural world and to tribal treaty rights guided and drove him in his efforts to protect them. He was one of the first Nez Perce to reopen tribal fishing at Rapid River, a small tributary to Idaho's Salmon River, back in the early 1970s. This small river became a flashpoint of controversy between the state of Idaho and the Nez Perce over tribal treaty fishing rights in 1980. Elmer was a key tribal leader of the tribal fishermen in this conflict. He was always ready and willing to take a stand to protect tribal treaty rights when they were threatened, and he was also always prepared to protect salmon and other species that made up the web of life of his homeland.

In his later years, Elmer worked for the Nez Perce Tribe Fisheries Department's resident fisheries program. In this role, he was responsible for protecting and restoring the non-migratory fish species living throughout Nez Perce Country. One of his favorite projects was reclaiming a railway dumpsite outside of Orofino near his childhood home. He turned the location into a healthy trout pond with a surrounding park called Tunnel Pond that is open to both tribal and non-tribal members of the community. It was always a source of pride to Elmer that Tunnel Pond became a place where anyone and everyone could catch and eat a fish. The city of Orofino approached Elmer, asking permission to rename the location Crow Pond, but Elmer demurred, insisting that it had always been called Tunnel Pond.

Given his body of knowledge and dedication to the natural resources of the region, Elmer's role expanded into cultural presentations and outreach throughout North America. In these presentations, he shared the Nez Perce culture via stories, legends and a multitude of traditional items, tools and weapons he made himself. Over the years, he gave presentations to tens of thousands of people. He particularly valued and enjoyed giving presentations to children, hoping to instill in them a connection to the natural world and an appreciation of American Indians and American Indian culture.

His disarming style of humor, wealth of knowledge, integrity and his genuine care and interest in people made him memorable to everyone who knew him. He would invariably end scientific insights, biological knowledge or quotes from legal rulings with his favorite catch phrase, "but I'm just a poor, uneducated reservation Indian" and then savor people's reaction to the irony. People went away from interactions with him feeling like they were important and valuable to him and that they were cherished or respected. He was impossible to forget, and thanks to his impressive memory, he rarely forgot them in return.

Following a series of heart problems and surgeries, Elmer felt he was living on borrowed time and was determined to make this "bonus time" count. He dedicated even more of his life to ensuring the traditional teachings, values and techniques he was taught as a child would be preserved. In the early 2000s, Elmer constructed the first Nez Perce bighorn sheep horn bow to have been made in 60 years, and it was likely that he was the only person still alive to know the technique for building it. He would never write down the involved, three-month-long method, insisting on passing the knowledge one-on-one only to individuals he trusted to use the skill to preserve Nez Perce culture.

Around the time of Elmer's heart problems, the already-low Pacific lamprey returns to Idaho began to plummet. Once returning in the millions, in 2009 only 12 lamprey passed Lower Granite Dam, the last major dam before they reached Idaho. Elmer took up this cause, pouring his heart and soul into ensuring the lamprey - or "eels" as he always called them - would be rescued from the brink of extinction. He worked tirelessly with tribal, state, and federal agencies in his mission to save them. He almost single-handedly drove lamprey recovery from obscurity to a funded, active program with regional support. Now huge agencies feature eels in their lists of priorities, and "Eelmer" (as he was known) is responsible for that. His actions not only resulted in a Nez Perce translocation program - where lamprey trapped at lower Columbia River dams are transported to Idaho to be released in tributaries throughout north central Idaho to spawn naturally - but also drove federal and state policy and program management changes to provide resources for this under-appreciated and forgotten fish. His passion and concern was contagious, instilling many people, from federal agencies to the general public, with a desire to help the lamprey and an appreciation for Elmer himself. Driving home after the tragedy, one of the grandsons he had helped rescue asked Lynda, "Oh no! What is going to happen to Papa's eels?" That this was what his grandson thought of, at such a time of loss, is testament to Elmer's teaching and dedication, as well as confirmation that his work to bring back the eels will live on.

Elmer is survived by his wife Lynda; children Jeremy (and Margaret), Jarrod (and Amanda), Jayson and Jamie; and six grandchildren, Khia, Dane, Phinn, Lucy, Sophie and Henry. He is also survived by his chosen mother Beula Worthen; his sisters Joyce Admyers, Elizabeth Crow, Bernie Lasarte, and Brenda Moses; and his brothers Reggie Crowe, Jeff Crow, Louie Lasarte, Raymond Lasarte, Billy Henry,and Emmit Taylor. Preceding Elmer in death were his parents Elmer Crow Sr. and Hattie Lasarte; and siblings Wendell Crow, Gregory Crow, Ed Crow and Annie Lasarte.

A memorial will take place at 5 p.m. Thursday at the Pi Nee Waus Community Center in Lapwai. A service will be at 9 a.m. Friday at the Pi Nee Waus Community Center, with interment at the Jonah Hayes Cemetery in Sweetwater, followed by a luncheon at the Pi Nee Waus Community Center.

Memorials may be made to the Elmer Crow Memorial Fund, care of the Nez Perce Tribe, P.O. Box 365, Lapwai, ID 83540. The fund will be used to further the cause of rescuing the Pacific lamprey from extinction.