Weed eaters

Idaho's tiniest soldiers - insects - are deployed in the war against invasive plants

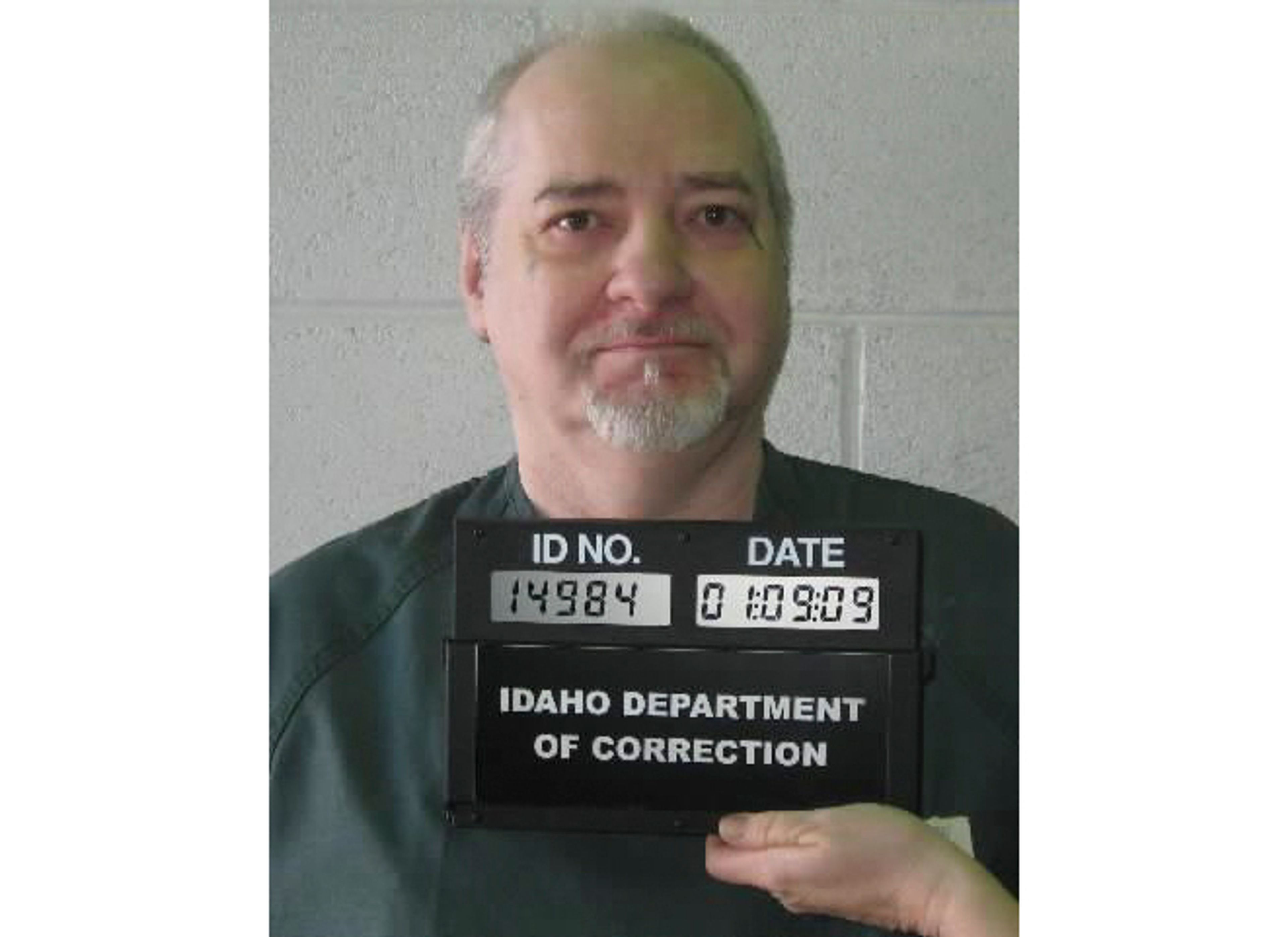

LAPWAI - One of the questions Paul Brusven, coordinator of the Nez Perce Tribe's Bio-Control Center at Lapwai, hears most often about the insects that have been deployed to combat some of Idaho's noxious weeds is: "Do they work?"

For decades now land managers, landowners and others have been installing colonies of insects in areas where weeds such as yellow star thistle, Dalmation toadflax and spotted knapweed have gotten a grip, strangling out native vegetation and rendering the landscape useless.

Millions of acres statewide have been infested by these invasive species, and in Nez Perce County alone yellow star thistle is prevalent on more than 500,000 acres of rangelands, roadsides, pastures, recreation lands and cropland.

Although most people who work with invasive weeds acknowledge it's a scourge that will never be completely conquered, Brusven has the data to show that biological-control insects are, indeed, having an impact on the proliferation of noxious weeds.

"There seem to be a lot more questions than there are answers," Brusven said. "But one thing that's really cool about bio-control - once you get these natural enemies, these insects, established, there's a continuous mode of action against target weeds.

"I think of bio-control kind of like the army guys fighting the war of weeds. We get those guys out there, and they're boots on the ground. They're marching up those steep and rough terrains. So together with all the tools that we have, I think we can make a strategic impact in different areas if we use the tools correctly. So, yes, we're making progress."

The gold-and-black weevils that make up the army that attacks the yellow star thistle are described as having "racing stripes" and are about the size of the tip of an adult's pinky finger.

According to the Idaho Department of Agriculture, 67 species of noxious weeds have been designated by state law. They are plants that are not native to Idaho and do more harm than good to the environment.

Noxious and invasive plants are estimated to cost Idahoans $300 million each year in direct damages. Costs include fighting wildfires on rangelands and forests and the destruction of wildlife habitat and productive grazing lands for livestock in areas where invasive plants have proliferated. Landowners and land management agencies spend about $25 million annually to control and manage noxious weeds, but the creep of invasive species continues to claim thousands of acres each year.

In 1999, at the request of the state agriculture department, the Nez Perce Tribe opened its bio-control center dedicated to cultivating insects proven to be natural predators on certain noxious weeds. It is the only tribe in the United States to have such a program, Brusven said.

These insects are imported from the same areas - usually in Europe and Asia - where the invader plants originated. They go through a rigorous screening process, Brusven said, to make sure the insects are target-specific - meaning they will feed only on the intended invasive species and not harm other vegetation. This process costs about $1.5 million per insect species to ensure it is safe to release in the United States.

In 2007, Brusven and his staff worked with scientists from other agencies and universities to develop a strategic plan to measure specific sites throughout the state, documenting all vegetation and bio-control insects within the perimeter of the sites.

The researchers review the sites each year, and over time have been able to witness measurable results.

"We have over 360 sites in Idaho we monitor every year, and we can see trends in which the weed might go down and it might come up. And we correlate that with the level of population of bio-control agents in that area," Brusven said.

"So, for yellow star thistle, in some areas we're actually seeing a reduction in a number of stems and with a reduction in the number of stems, we're getting a reduction in the number of seeds that are being disbursed from those mother plants.

"One thing a lot of people need to remember is, with bio-control it's not an eradication of the target weed. It's more of a reduction in the weed where a balance is made. It's kind of like a prey-and-predator cycle. And over time we want to see that cycle continue, but we want to see it where the target weed is dramatically reduced and re-establish the balance in nature."

Students take on star thistle

For two days last summer, high school students from Kamiah and Kooskia hit the trails along the South Fork of the Clearwater River from Kooskia to Blackerby to make a charge against yellow star thistle.

The students were members of the Clearwater Basin Youth Conservation Corps, under contract with the Idaho County weed department.

Weed department coordinator Connie Jensen-Blyth said students were equipped with hand-held recorders showing previously mapped locations of yellow star thistle infestations, along with small containers filled with 8,200 weevils. The weevils feed on the seed heads of yellow star thistle.

"What I hear most often from the community is: 'How come you guys aren't doing more about these weeds that I see spread throughout the whole landscape?' " Jensen-Blyth said. "You try to explain: We have to prioritize. This is large-scale infestation. And it occurred to me we don't have a very good story line to share. But there is something going on - it's just at a time-scale that is really, really slow.

"So we got these kids and trained them how to use mobile data recorders, so they got some exposure to new technology. They got some exposure to these bio-control agents. They got some exposure to noxious weeds of concern in our county. And they really got some exposure to some hard work because these are steep, rugged, hard areas to get in and out of, and it was hot and it was miserable and it probably wasn't their favorite project. But I really feel like they learned a lot."

The students used sweep nets to collect insects and count them, and they released new insects at the infested sites.

That data was then shared with the Nez Perce Bio-Control Center, and scientists there were able to determine that previous releases of seed-feeding weevils have effectively batted down much of the star thistle.

The scientists "could tell, in these areas closer to Kooskia where the releases originated, you can see the patches and you can see the changes in vegetation," Jensen-Blyth said. "They tell a story, and you can see that yellow star thistle was this big, and now it's shrunk down to this big. The (plant) species around them has changed, and the surrounding vegetation is different and it's preventing any larger explosions.

"So it was really like a bright light."

The cost of the project to the county was about $20,000 to pay the students, but the insects, provided by the Nez Perce Bio-Control Center, were free. Brusven explained that the center is funded in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the farm bill, and for that reason the insects are provided free of charge.

Idaho County plans to enlist the youth corps again this summer to release a different type of insect that is known to feed on the roots of spotted knapweed. Those releases will take place from Blackerby, which is at the intersection of State Highway 13 and State Highway 14, east to Newsome, about 10 miles from Elk City.

Jensen-Blyth said people have to be realistic and understand that invasive weeds on large landscapes will likely never be fully stomped out.

"But it doesn't mean that we can't tweak some of the things that are going on out there by utilizing things like bio-control to help restore some of that balance. There's lots and lots of good reasons to continue to do what we're doing. We have new invaders that are coming in constantly. We're trying to prevent them from gaining a foothold and expanding their infestations and becoming the next yellow star thistle crisis."

Not a silver bullet

State Sen. Carl Crabtree, R-Grangeville, was the first in the state to organize a cooperative weed management area and received a state award for his work in 1994. Crabtree then was the weed coordinator for Idaho County.

Cooperative weed management areas are coalitions of county, state and federal agencies, along with Indian tribes and private landowners. There are 34 such groups in Idaho.

Although he has not actively participated in the noxious weed campaign for four years, Crabtree keeps an eye on the progress of people working with bio-control agents and other means to retard the spread of invader species.

In spite of encouraging reports from Idaho County and other areas, invasive weeds "are still improving their territory about 12 percent a year," Crabtree said. "So while those insects might be helping, (the weeds) are still expanding at a pretty fast clip."

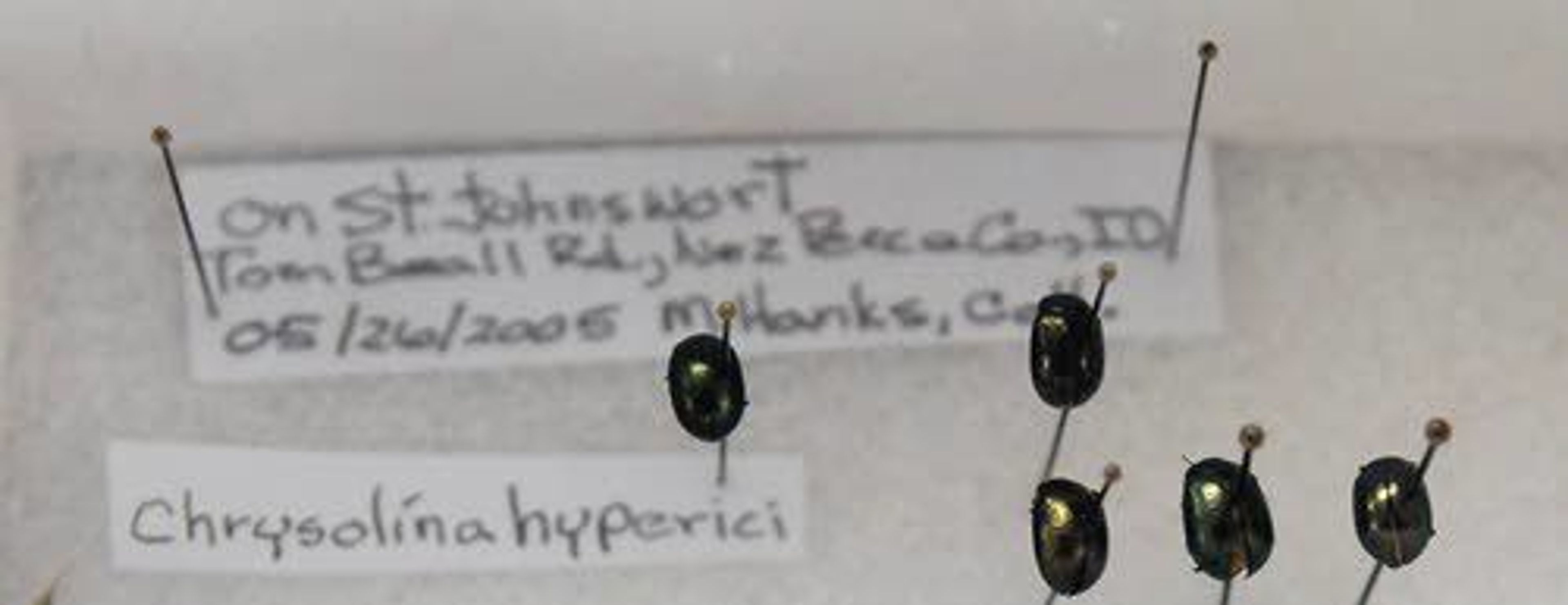

Bio-control insects were first used in this area in the 1940s when a beetle was deployed to fight infestations of St. John's Wort, also known as goat weed.

Crabtree said the beetle was hugely successful and was considered "the silver bullet" on the war on weeds.

But the insects are not as effective as they used to be.

Once the insect has depleted the population of the noxious weed, it dies off. When the weed starts up again, there is a lag time before the insect population also builds enough to knock it back down.

Crabtree said he considers bio-control insects "a moderate success. It is a tool, but I would say it's not the silver bullet that we hoped it would be like it was back in the day with goat weed."

Hedberg may be contacted at kathyhedberg@gmail.com or at (208) 983-2326.