GRANGEVILLE - This is a story that you never read because I couldn't get it before.

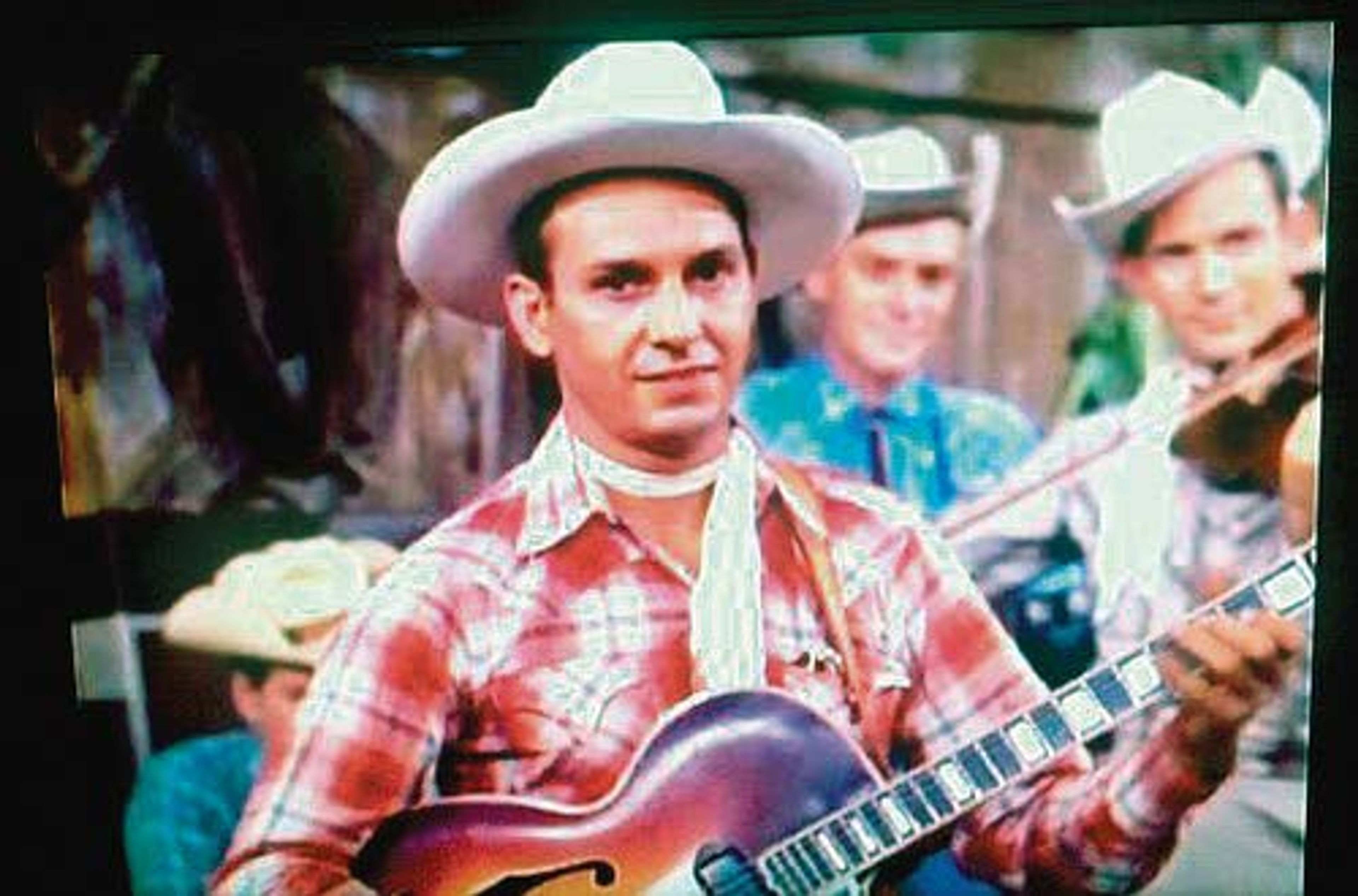

About 10 years ago some friends of mine, fellow musicians, told me about a man in town named Joe E. (Billy) Byrd who had been one of the premier guitarists of the 1950s and had performed and toured with the likes of Ernest Tubb, Bob Wills, Little Jimmy Dickens and other famous musicians.

I called Byrd a couple of times and asked if I could do a story about him. Each time he refused. I even tried to get our mutual friends to persuade him, but he wouldn't budge. When I asked why he wouldn't let me do the interview, he explained that once when he was living in Yakima he'd given an interview and the next morning there were fans and groupies all over his doorstep. He wouldn't risk that again, he said.

So I gave up and told one of my friends that the only way I'd ever get that story was when Byrd died.

Last Monday he did, at age 89, at his home in Grangeville.

Two of my music buddies, Pete Northcutt - a masterful musician himself - and Scott Scribner, both from Grangeville, played music with Billy Byrd from time to time and have filled me in on his story.

Byrd grew up in Nashville and got a start in show business after winning a vocal contest against a famous singer on the Grand Ole Opry. In 1949, Byrd started playing guitar for Ernest Tubb's Texas Troubadours, where his career caught fire.

"He was part of that Nashville group," Scribner said. "He traveled with Ernest Tubb for awhile (and performed) on his most famous records in the '50s." On these old records, Tubb would have Byrd take an instrumental break and was often heard saying: "Ah, play it pretty, Billy Byrd."

It was a typical musician's life, Scribner and Northcutt said, with lots of drinking and carousing.

"He said they very seldom performed sober when he was with Ernest Tubb," Scribner said. "It was a constant party for years."

At one point, Northcutt told me, Byrd was kicked off Tubb's tour bus, ending his tenure with that band.

"The story is everybody got kicked off the bus at some point when you played with Ernest Tubb," Northcutt said. Another musician stepped in to fill Byrd's place and also took the name "Billy Byrd."

The real guy married a woman named Maxine, who objected to the lifestyle he'd been living. For her sake, and for his own health, Byrd quit the business and went to work driving truck for Pacific International Express. He'd lost all the money he'd made as a performer and when the trucking company went broke, he lost his pension there, as well.

Sometime in the last couple of decades, Byrd and Maxine moved to Grangeville, where she had relatives and Byrd led a quiet life of seclusion.

One day Northcutt was carrying his musical instruments across a parking lot when Byrd spotted him and struck up a conversation. Northcutt said he was going to play music and invited Byrd to join him, but he declined.

Later, however, Maxine broke a strict policy of not permitting other musicians to play music with her husband and allowed Northcutt to come to their house.

"When we sat down to play there was enough rust there he was lucky to make a chord," Northcutt said.

But he practiced and eventually the two started making music.

Byrd played an old, beat-up guitar with a warped neck. In his heyday, however, the Martin Guitar Co. built him a custom semi-hollow-body electric guitar that was, no doubt, worth tens of thousands of dollars. In 1970, Northcutt said, Byrd was so broke he sold the guitar for $100.

The beat-up guitar he was using made it challenging for other musicians to keep up. Byrd would tune it two to three musical steps south, Northcutt said, and when they played together Northcutt and Scribner tuned to him, no matter what the electric tuner said.

"He kept saying, 'Well, we're in G,' which we weren't," Northcutt said. "It was one of those cases that you're sitting with a legend. He's telling you you're in the key of G but then he'd be flat so there is no way it would harmonize.

"Without a doubt he was a master," Northcutt said. "He really liked to play the jazz-style chords and the last time I sat with him (about five years ago) he didn't miss a key."

Ironically, Byrd was reported in the Nashville news media to have died Aug. 7, 2001, but he was in Grangeville all along.

Byrd had been in the hospital shortly before he died. He returned home and the night before his death Scribner visited him and took him a chicken enchilada casserole.

"I'll say, he was one of the most polite people I've ever met," Scribner said. "Very nice and unassuming and shy. But as a performer he jumped right out there and took his leads and he knew music.

"He was a real Southern gentleman, in the old tradition, of anybody you'd ever meet. So I couldn't overemphasize that he was a really nice guy."

---

Hedberg may be contacted at kathyhedberg@gmail.com or (208) 983-2326.