Quieting war's memories

Lewiston man uses writing and artwork to deal with difficult past

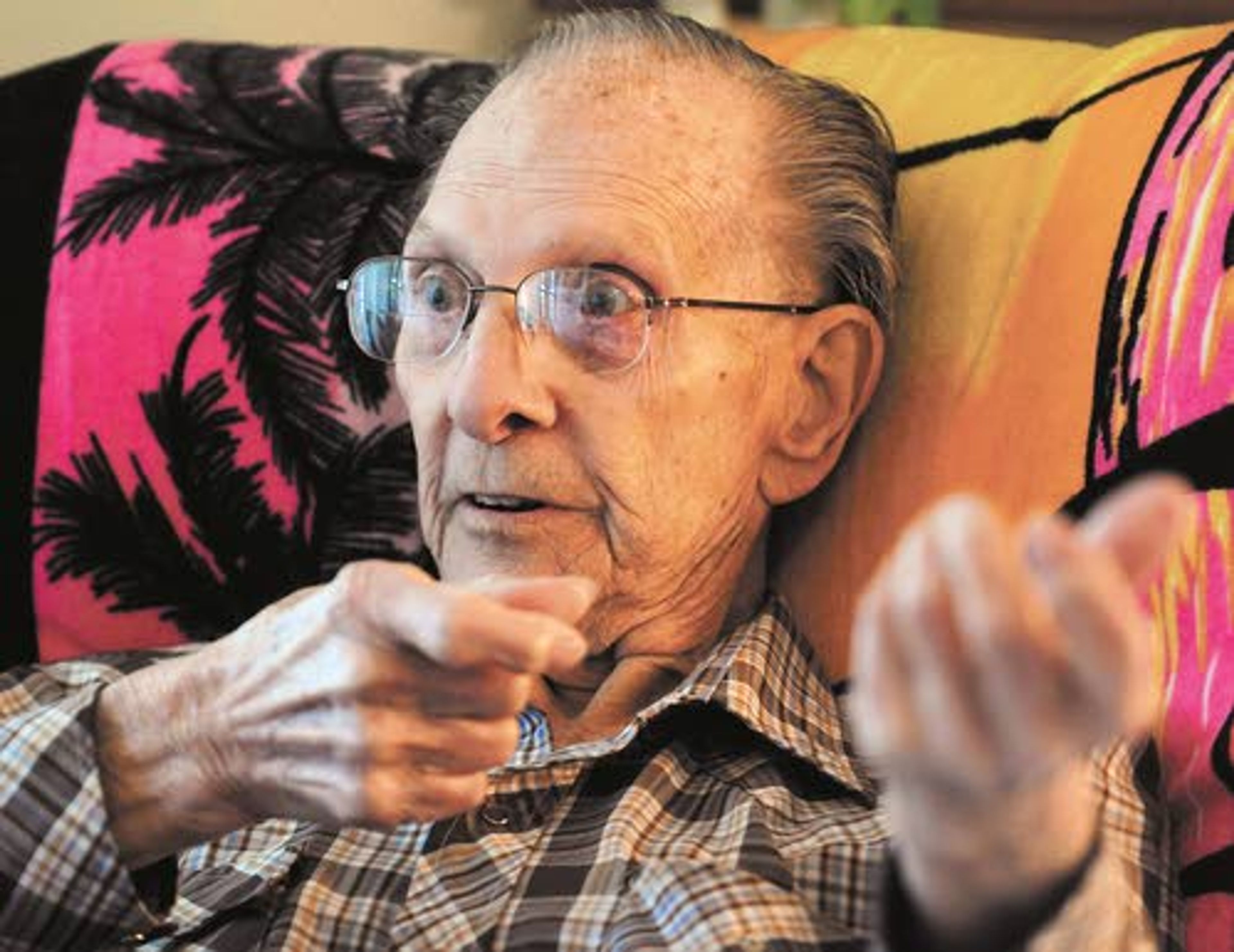

Forty-five years ago, Melvin R. Meisner started writing down all the stories he could remember from his war years. The stack of paper is more than 2 inches thick.

"I think I've seen everything you can see as far as war is concerned," he says simply. When he started writing, "things were driving me crazy."

Putting them on paper, as stories, and on canvas and feathers and glass as pictures has helped.

Meisner, 88, and his longtime companion, Clara Young, 79, live on Normal Hill in a small house surrounded by flowers and a fence where cutouts of quail atop the slats make it an instant landmark.

They have been together for close to 30 years. He asked her to marry him once, but her response was, "don't fix what isn't broke," Young says.

They met in Oceanside, Calif. She called the Kmart automotive department he managed and asked about the noise her Mustang was making.

And how, he asked, was he supposed to diagnose it over the telephone? She told the other women in her office she was going to go kick his behind, but when she got there, "he was so cute, I couldn't be mean to him."

Living together has meant consolidating families - she has four children and he has two, and today's Father's Day cards were coming from hers as well as his - and learning to live with the handicaps that war created.

Early in their relationship, there were lots of nights, Young says, that she waited for him to drop off to sleep and then moved to the couch before the nightmares started.

He was 16 when he enlisted on Dec. 9, 1939, two years before Pearl Harbor. It was easier to lie about your age and get away with it in those days, he says, pulling out a newsletter from Veterans of Underage Military Service.

The only requirement for full membership, according to the organization's website, is military service before the age of 17, or 16 for World War II Merchant Marine vets, and younger than 20 for women veterans of WWII.

One deceased member, according to VUMS, served in combat at the age of 12, and 29 first served at age 13. Most were between 14 and 16.

Meisner ran away from home to enlist. His father died when he was 11 months old and he didn't get along with his stepfather. So he ran away, got caught, and ran again until the last time, when the Army got him.

As luck would have it, he spent more time on ships than most sailors, he says, starting with being loaded on a troop ship at Seattle headed for Alaska. "I got seasick while we were still at the dock."

He landed in the Aleutians, barely escaping drowning when the wind caught the barge he was transferring to from the ship and pulled him away from it. He landed in the water. They were wearing 90-pound packs plus pistol belts and boots, and more than one man died that day, he says.

He was fortunate enough to catch hold of something and was dragged to shore, miserably cold, but alive.

He was at Adak, Attu, and Kiska Island, and at Dutch Harbor when the Japanese launched their air strike. He was on Guadalcanal at the battle for Bloody Ridge and then was sent to the Marshall Islands. "That was very fierce, hard fighting."

He was greeted on a black sand beach by a soldier asking for a cigarette. The man was still smoking it when he was hit by something that blew him into a million pieces, Meisner says. They had to leave him there on the beach to seek cover. "So this guy, he bothered me until about 1970. I'm kind of an artist so I painted him. He's out in my shed. I go out there and talk to him once in awhile."

In addition to writing and painting, he chips arrowheads out of obsidian and window glass, the latter because it provides depth, and paints pictures of flowers and wildlife and war on them and on turkey feathers friends bring him.

His stories, all from his personal experience, he says, include one of a soldier who parlayed stolen silverware into a Purple Heart and a ticket home. And a man who killed a Red Cross worker in an unsuccessful attempt to go home to see a dying sister.

He survived being stabbed by an enemy soldier, and figures he killed his share of the enemy.

Meisner said he was sent home from the Pacific in 1944 and after a week's leave at home was sent to Europe. He was at Bastogne and saw the inside of three of the German death camps.

Meisner's voice breaks as he talks about frozen C rations, being wet, cold and dirty, and making a friend only to watch him die.

He hated the brutality of the Japanese and the Germans and Gen. George S. Patton. "He was the worst soldier there ever was," Meisner says. "He killed soldiers by the thousands. He didn't care who you were, which army."

He got moved around a lot, Meisner says. "You go into outfits and don't know anybody. You make buddies out of them and then they get shot and you hold them while they cry for Mama. I never heard anyone call for Dad."

He was about 22 when he was finally sent home, and the Army was all he knew. He knew how to shoot and how to smoke, both learned in the Aleutians, and he went to work as a salesman for the Philip Morris Co., selling cigarettes.

"The way I felt about cigarettes, it acted like a meal. It satisfied my hunger."

He quit when he was 74 when he caught a cold and couldn't breathe.

"Now I write my stories, I paint my feathers and I chip my arrowheads, and I'm just as happy as a clam," he says.

"He is one of the most wonderful people you'll ever want to meet," Young says.

---

Lee may be contacted at slee@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2266.