Our national debt and 'the inability to govern'

As another session of Congress goes by with no budget agreement, many wonder if anyone will address 'systemic risk' to America?

WASHINGTON - Here are a couple of telling episodes from Congress' long-running budget horror story:

May 5, 2015: For the first time since 2001, the House and Senate approve a concurrent budget resolution that balances the federal budget within 10 years.

"Republicans are making our vision very clear," crowed House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., at the time. "In our vision, Washington lives within its means."

Yet before the month is even out, lawmakers enact legislation that breaks the budget. Over the following year, they increase spending by $150 billion and slash revenues nearly $500 billion.

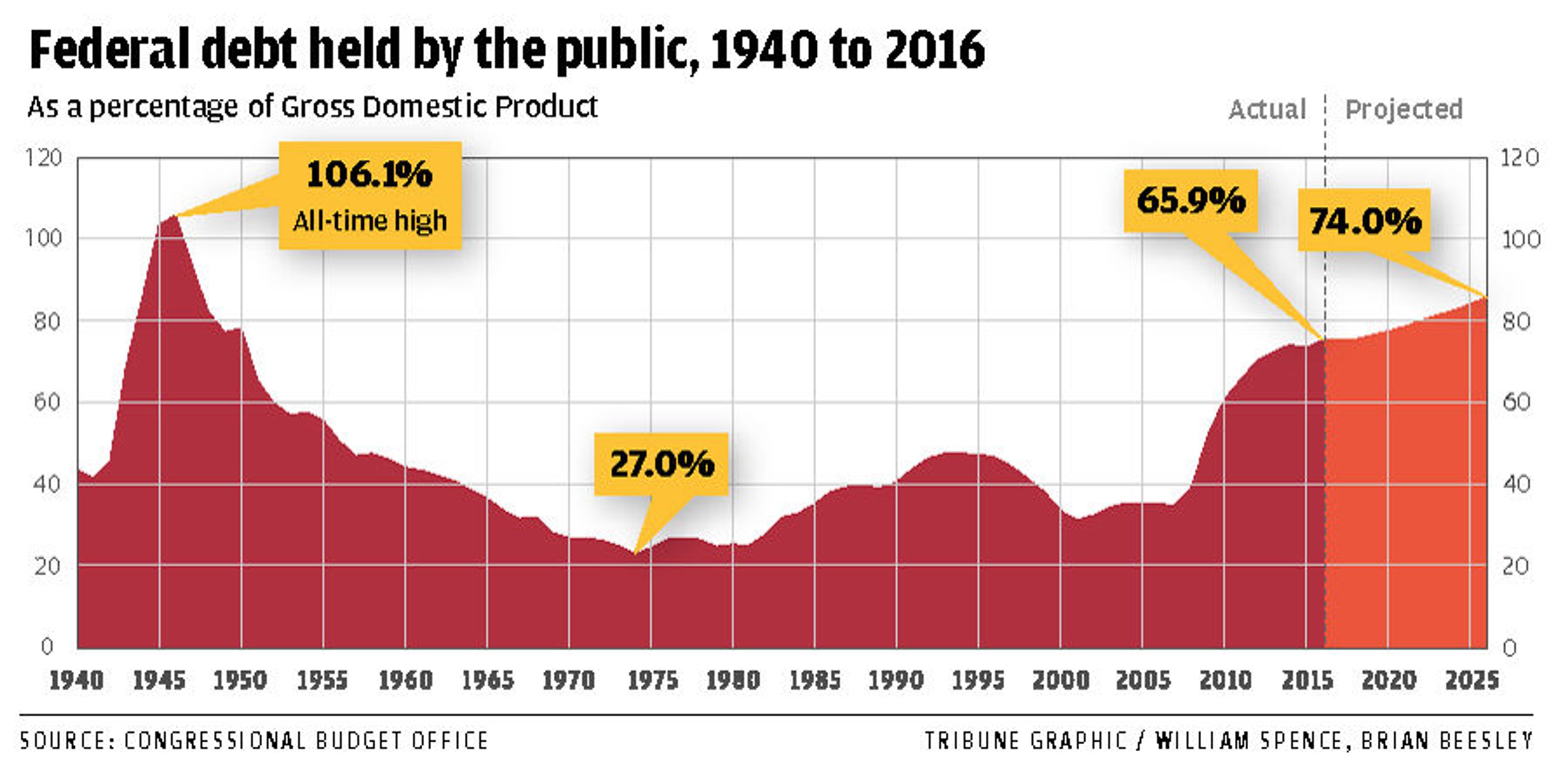

Budget deficits are now projected to average $930 billion per year over the next decade. The national debt will increase from $19 trillion to $29 trillion by 2026; interest on the debt will become the third-largest expense category, ahead of national defense or non-defense discretionary spending.

July 14, 2016: Congress leaves town for a seven-week summer recess, once again throwing in the towel on its annual budget process.

Despite having failed to advance a budget through both chambers - or any of the 12 appropriations bills needed to fund government operations - lawmakers go home. When they return after Labor Day, they'll have less than four weeks to avoid a government shutdown before the fiscal year ends Sept. 30. Then they leave town for another six weeks.

---

Maya MacGuineas, president of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said this inability to pass a budget and control federal spending is what Americans think of first when they talk about congressional dysfunction.

"Right now there's so much concern about the breakdown in Washington, about the inability to govern," she said during a congressional hearing in June. "I believe the budget is the first step in showing that you can govern, that you can make tough choices and come together on solutions that both sides can agree to and stick with."

Perhaps no one in Congress agrees with MacGuineas more than the members of the House and Senate budget committees - and for the first time in a generation, they seem prepared to do something about it.

Both committees held multiple hearings earlier this year, examining problems with the current budget process and considering ways to improve it.

The intent, according to House Budget Chairman Tom Price, R-Ga., is to draft "a complete rewrite" of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 and replace it with a process that focuses attention on national priorities and long-term policy goals.

"Nothing could be more important or less exciting," Price said. "We know budgets aren't simply spreadsheets. They're reflections of our governing philosophy and our priorities. We ought to have a process that understands this and that focuses our energy on goals beyond merely the fiscal health of the country."

Congress rarely meets requirements of 42-year-old Budget Act

The basic process for adopting the annual federal budget starts with the president, who is required to submit his budget recommendation to Congress by the first Monday in February.

Congress then adopts a budget resolution by April 15. This nonbinding document provides a fiscal blueprint for the coming years, outlining total revenue, spending and debt levels and, most importantly, setting the discretionary number that's used to fund most government operations.

Finally, the House and Senate appropriations committees take the discretionary amount and divide it among the various federal agencies. They draft 12 separate appropriations bills, which are supposed to be signed into law before the fiscal year ends Sept. 30.

While this process is set in statute, it almost never works that way in reality. The president may ignore the February deadline, the House and Senate often fail to adopt budget resolutions and Congress almost never passes all 12 appropriations bills before the fiscal year ends.

In fact, in the 42 years since the Budget Act was adopted, Congress has only met the requirements of the law four times. More often, stop-gap funding bills are needed to keep the government running while an "omnibus" budget deal is hashed out behind closed doors.

"Today, budgets from Congress and the president are increasingly tossed aside, leaving the country with no long-term fiscal plan," said Senate Budget Chairman Mike Enzi, R-Wyo., in a recent speech.

Another major problem, Enzi said, is that discretionary spending - the money allocated through the 12 appropriations bills - only accounts for about 32 percent of all federal spending. Mandatory appropriations for Social Security, Medicare/Medicaid and other entitlement programs make up the remaining 68 percent - and none of that gets reviewed on an annual basis.

"With mandatory spending, there's no connection between funding decisions and program performance," Enzi said. "There are a bunch of programs we never look at because (by law) they're going to get their money anyway."

Other problems highlighted during recent hearings include:

- Weak enforcement - Even when Congress approves a budget and passes appropriations bills, it's relatively easy to skip past the spending limits by declaring an "emergency."

"Congress has a nearly perfect record in breaking every budget it adopts," said Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, who sits on the Senate Budget Committee.

- Unauthorized programs - Almost a third of all discretionary spending, or more than $310 billion this year, went to programs whose authorization has expired. That means Congress is appropriating money for programs without periodically checking to see if they're still needed, still operating efficiently and still accomplishing their goals.

- Tax expenditures - Just as mandatory spending isn't reviewed each year, the budget ignores the $1.3 trillion in foregone revenues that are lost through various income tax credits, deductions and exclusions. These annual "tax expenditures" exceed all defense and non-defense discretionary spending combined.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that half this revenue goes to the top 20 percent of income earners, with 17 percent - about $200 billion per year - going to people in the top 1 percent.

One budget fix focuses on broader policy goals

Having identified a number of weaknesses with the current budget process, the House and Senate budget committees also considered various alternatives.

Most states, for example, have separate operating and capital budgets, using the latter to account for large, one-time expenditures on vehicles, buildings, infrastructure and other major assets. The federal government doesn't do this.

John Hicks, executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers, told the House Budget Committee that capital budgeting typically requires agencies to plan long-term and forces them to compete for resources, leading to better funding decisions.

Another relatively new option that Chairman Price seems to favor is portfolio budgeting.

Federal agencies often have competing programs aimed at the same broad policy objective, such as expanding higher education opportunities or improving workforce development. The budget process, though, focuses on incremental changes in agency expenditures, rather than policy goals.

Portfolio budgeting would let Congress review all spending related to a given policy, evaluating which programs work best and adopting government-wide performance goals.

"Portfolio budgeting accounts for the full range of fiscal policies that promote broader national priorities," Price said. "It's a more holistic perspective."

Other changes that have been discussed include moving to a two-year budget cycle to provide greater certainty, beefing up enforcement mechanisms to make it harder to break the budget, and adopting long-term fiscal targets for revenues, spending and debt.

Debt and spending reform 'not in vogue'

Whether Congress has the political will to make these changes, though - much less balance the budget - is something its own members are skeptical about.

"I think it's going to be a big fight," Crapo said of the reform effort. "The reason is because Congress and the president have grown accustomed to just borrowing money to resolve their disputes. That makes it easy to avoid hard decisions."

Congressman Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, spent eight years on the House Budget Committee. He described it as "the most partisan committee in Congress."

"It's where Republicans lay out what they want to do for the next 10 years and Democrats lay out their plan, and they never reach consensus," he said.

Both budget committees were created by the same 1974 act that established the current budget procedures. Prior to that, the appropriations committees handled everything.

"I actually think the budget committee isn't needed," said Simpson, who now serves on the House Appropriations Committee. "The appropriations committee used to do it and did a better job. We're the only committee that's actually reduced the deficit, because we've been cutting (discretionary) spending."

House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., a former budget committee chairman, is supportive of the reform efforts. However, he also knows how difficult it is to make changes.

In 2011, when he was chairman, the committee came forward with 10 reform bills aimed at strengthening budget enforcement mechanisms, requiring periodic program re-authorization, shifting to a two-year budget cycle and capping total spending - many of the same reforms Price and Enzi are now considering.

Six of the bills never made it to the House floor; the other four passed the House, but died in the Senate.

Rep. Mark Sanford, R-S.C., said he's seen Congress get excited about these reform efforts in the past, only for them to peter out when some new political crisis comes along.

"I'm in need of hope," he said in a June 22 hearing.

"If you look at the numbers, it seems to me this (fiscal situation) is a systemic risk for the American civilization," Sanford said in an exchange with William Hoagland, senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center. "But debt and spending aren't being talked about in the presidential election. Even in Congress, except in hearings like this, it's just not in vogue. So are there any examples of major powers that have been able to reverse course on spending?"

"Not to my knowledge," Hoagland replied. "But (former White House budget director) Leon Panetta said this issue would be resolved in one of two ways: through crisis or through leadership. It really comes back to leadership. That's the way you're going to resolve this."

---

Spence may be contacted at bspence@lmtribune.com or (208) 791-9168.