Once more into the breach debate

Former Army Corps of Engineers insider says numbers support removing the dams

Once a company man, Jim Waddell now finds himself challenging the agency he spent a career serving.

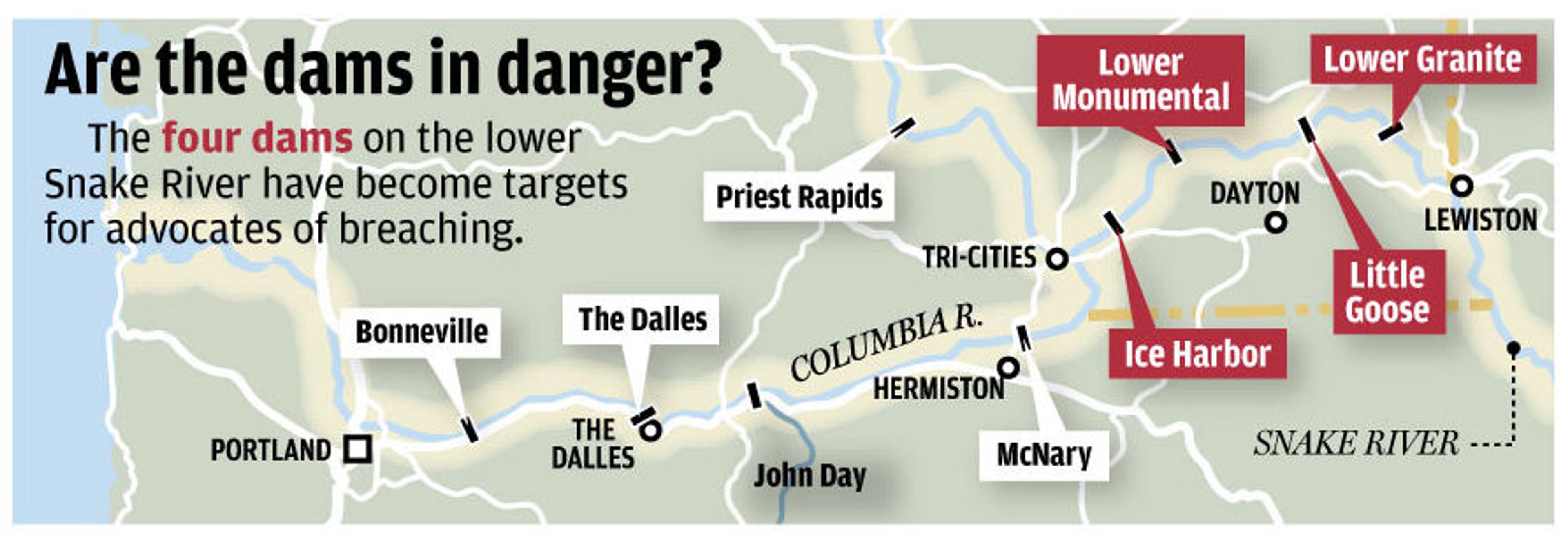

In so doing, he has established himself as a threat to those defending the four lower Snake River dams and a champion of breachers, who have adopted a new strategy that questions whether the massive costs associated with operating and maintaining the dams is money well spent.

But Waddell doesn’t see himself as the enemy of his former employer. Instead, he is trying to work with the agency and Congress in hopes of correcting what he views as a wrong he helped to perpetuate almost 15 years ago.

It was then that he served as the deputy district engineer — the top civilian at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Walla Walla District — at a time the agency was on the precipice of a monumental decision: Should the dams be breached to save threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead that spawn in the river and its tributaries?

Waddell was a key decision-maker and recommended the agency pursue breaching. He felt there was something wrong with the economic analysis that showed breaching the dams would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and keeping them would produce modest economic benefits.

“Being a program manager in the corps of engineers for a couple of decades, you know when something is not right. You can’t always come up with the right numbers. You just have to say, ‘This sucks, I don’t buy it.’ I had no recourse, I just said, ‘It’s not convincing economics and it’s not convincing biology.’ I said, ‘I recommend we continue with breach planning and prepare to do it.’ ”

His advice was ignored and the agency embarked on a strategy to invest hundreds of millions of dollars to make the dams more friendly to the fish.

Setting the record straight

Years passed, Waddell retired and now he is trying to make things right. Over the past year he reopened the Lower Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Report, pored over its thousands of pages, charts and appendixes and did his best to correct it. He started by consulting some of the documents he saved during his time at Walla Walla. Chief among them were notes from a “team of rivals” exercise Waddell set up as the document was being completed. He formed two teams — one to argue for keeping the dams, and one to argue for breaching them.

The team that argued for breaching pointed out several problems with the economic work in the study:

- The alternatives that called for keeping the dams by adding things like fish bypass systems and removable spillway weirs assumed the money spent to do the work would be one-time expenditures, and failed to note the equipment would need to be maintained and even replaced throughout the 100-year lifespan of the dams;

- The cost estimates of the fish-friendly equipment were not realistic;

- All of the costs associated with maintaining the dams were not considered when calculating the avoided costs associated with dam breaching;

- The corps did not include indirect expenses to keep the dams, such as the cost to trap and barge fish, and other mitigation measures.

But the agency had spent six years on the study and more than $30 million and was unwilling to delay its rollout to fix the problems.

Over the past year, Waddell spent an estimated 600 to 700 hours correcting the feasibility study. When possible, he used the corps’ own documents to figure out how much maintaining the dams cost. One of the big-ticket items is the cost to rehabilitate aging turbines at the dams. At the time, the corps estimated it would cost $380 million. But the agency is now spending $97 million to rehabilitate three turbines at Ice Harbor Dam, or about $32 million per turbine. Waddell figured at that price it will cost $776 million to rehabilitate all 24 turbines at the four lower Snake River dams.

He also calculated the cost to decommission the dams at the end of their useful lifespan. He figured decommissioning the dams would be cheaper than a second turbine rehabilitation that would be required decades from now. The price to decommission came to about $20 million a year on an average annual basis.

Waddell also added in the cost to maintain and update the many hatcheries that exist to mitigate for the number of salmon and steelhead killed at the dams, and the money the Bonneville Power Administration will pay to maintain the hydroelectric system at the dams. He calculated the cost to dredge the navigation channel and to dredge the river to avoid flooding at Lewiston and Clarkston over the lifespan of the dams, and he applied interest and discount rates to his work.

Added up, it comes to $217 million on an average annual basis to operate and maintain the dams — $160 million per year more than the corps came up with. The corps, in its 2002 study, said breaching would cost an estimated $246 million on an average annual basis, and keeping the dams would cost about $22.8 million a year, plus another $33 million per year in avoided costs from not breaching.

“That is a big difference,” he said. “That is enough by itself, even if everything stayed the same, to push the net economic effect of breaching pretty close to zero. It might be minus $20 million instead of $246 million, but it gets it out of this really high cost.”

What he hasn’t done yet is compare the cost to keep the dams to the value of the benefits they provide. That is something he is working on, but his initial investigation leaves him to believe there are errors to be corrected and when he is done his work will show breaching will save taxpayers money.

Spreading the word

Waddell has been working to get his message to decision-makers. He met with members of Congress and officials in the office of Jo-Ellen Darcy, assistant secretary of the Army for civil works.

It’s not a message he likes to deliver.

“I really feel terrible, we get to this point and 15 years later ... I discover these errors weren’t $15 (million) to $20 million a year, but $160 million a year.”

There has not been an exhaustive review of the 2002 report in the intervening 13 years. Corps officials are aware of his work, but say their job is not to question their past report or Waddell’s work, but to maintain the system as authorized by Congress and that Congress is the appropriate venue for critics of the dams to air their concerns.

“They are talking to the right people,” said Lt. Col. Timothy Vail, commander of the Walla Walla District. “I’m an Army guy and we are focused on our mission and we are passionate about our mission.”

The way he sees it, the lower Snake River dams were authorized by Congress and it’s the corps’ mission to operate and maintain the dams and the associated navigation system, and not to further study the economics behind the dams or to fact-check Waddell’s work.

“It’s an existing project. If Congress tells me to do a reauthorization study, I will do one,” Vail said.

A new strategy

Although Waddell is working with the Save Our Wild Salmon coalition, which advocates breaching the dams, he is not employed by the group. But Sam Mace of the coalition sees him as a valuable ally, an ultimate insider who is able to shine a light into the bureaucracy. She said his approach is a new strategy. The group has long argued that breaching the dams would lead to economic development via improved recreational and commercial fishing from the Snake River’s headwaters to the Pacific Ocean. But it hasn’t previously attempted to question the expense of maintaining the dams.

“What is so different about the work Jim Waddell is doing is having someone who worked in the corps and knows those numbers forwards and backwards,” Mace said. “Also, what is new is the obvious decline of the shipping and the value of that waterway, while it’s becoming increasingly clear the cost of keeping that waterway is much more than we originally thought.”

Waddell, Mace and Linwood Laughy, a critic of the Port of Lewiston and dredging who has worked with Waddell, argue the corps has maintenance and operation costs throughout the nation that outpace the agency’s available budget. They hope to convince the agency, Congress and the public that money used to maintain the lower Snake River would be better spent elsewhere.

“It’s becoming a reality that we have more infrastructure as a nation than we can afford to maintain. What are the pieces we can really afford to keep, whether it’s highway or John Day Dam (on the Columbia River) versus keeping four dams where the costs of keeping them is not providing the same kind of benefits,” Mace said.

Checking his work

Waddell and his allies know his position will be challenged.

“I know what their strategy will be. They will find a couple of things wrong with it and say, ‘He doesn’t know what he is doing so we will discredit the whole thing.’ What we ought to do is say, ‘OK corps, tell us what the number ought to be.’ ”

He’s right about the criticism. Kristin Meira, executive director of the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association, has seen a brief description of his work and quickly found problems.

“I don’t think he is accurate in his numbers,” she said.

She went on to say the Snake River dams are a critical piece of the Northwest’s transportation infrastructure and hydropower system. For example, the corps said replacing the power produced at the dam would cost an average of $271 million per year, a number that is larger than Waddell’s $217 million estimate of what it costs to keep the dams.

Terry Moreland, a retired economist with the Northwest Power and Conservation Council who served on an economic advisory committee associated with the feasibility report, said he isn’t surprised Waddell was able to find errors with the corps’ work. It was a massive undertaking that had to include several assumptions and cost estimates. But he said it was a solid piece of work.

“My impression of the corps’ study is while there is plenty of uncertainty out there in the analysis, they did as good a job as they could in trying to be objective. The problem of some aspects of those kinds of analysis are they are just highly uncertain and highly speculative.”

But others backed Waddell’s approach. Ken Casavant, an economics professor at Washington State University, said the process that Waddell uses is normal economic analysis. “Without knowing the source of his numbers, I think he is approaching the problem as an economist would and should.”

Laughy, Waddell’s confidant, said the numbers might be off here and there, but the work is generally solid and should change the debate over the dams.

“Let’s imagine Jim is overstating (the cost to keep the dams) by 100 percent. Cut his numbers in half, then they are understating — the corps knowingly understated the costs of keeping the dams by at least $85 million. Had that been on the table (in 2002) that easily could have led to the decision to breach,” he said. “But he’s not off by that much.”

———

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.