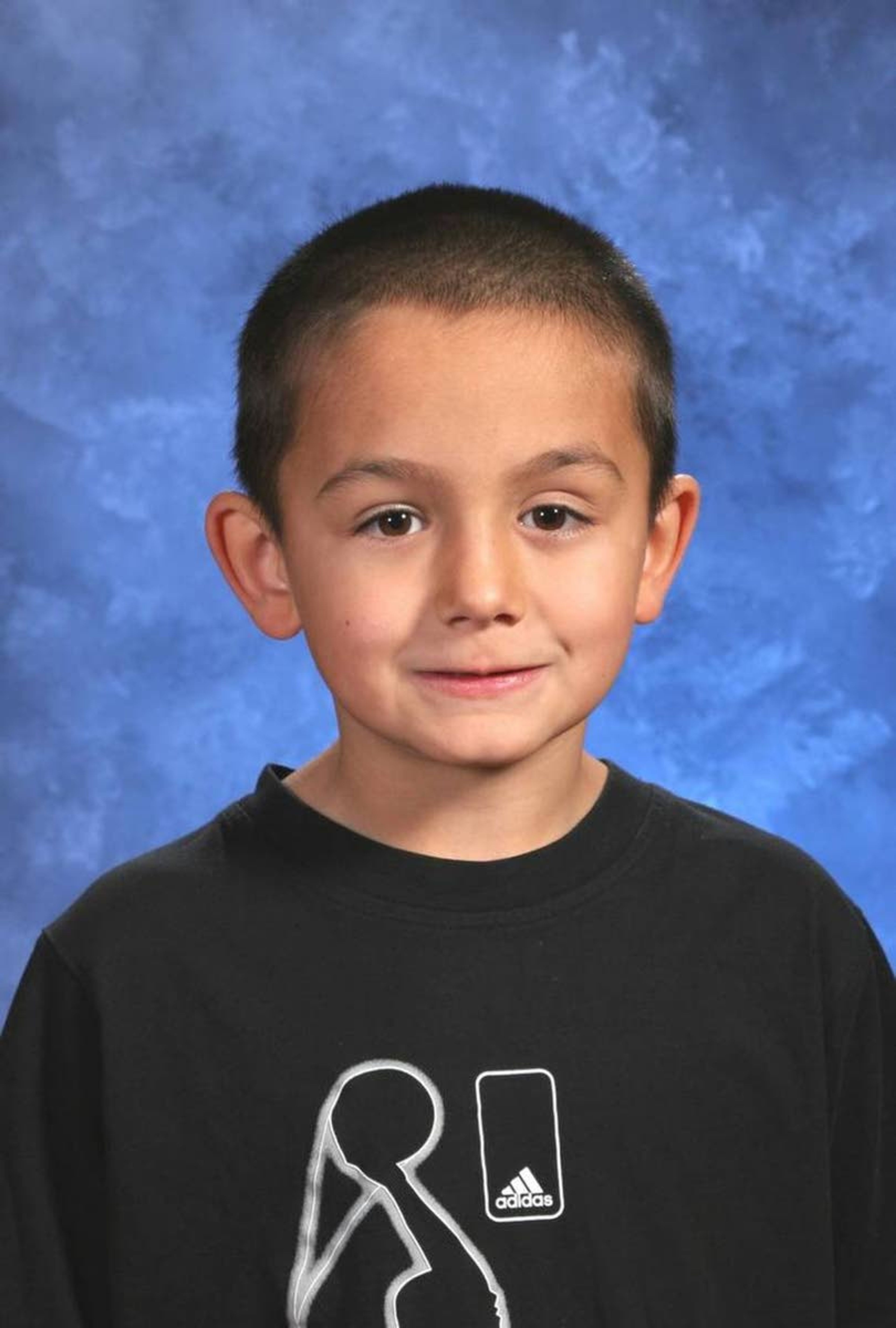

Murder of boy shaped his classmates

New Plymouth community keeps Robert Manwill’s memory alive after 2009 death

BOISE — More than 23,000 cases of possible child abuse or neglect were reported to Idaho health officials last year, according to state data.

With help, most children survive their physical and emotional wounds.

Robert Manwill wasn’t so lucky.

The 8-year-old, who lived with his father in New Plymouth and visited his mother in Boise, was beaten and tortured by his mother’s boyfriend. His mother helped cover up the abuse rather than stop it. The boy died, and he was dumped in a canal.

That was July 2009.

“It’s hard to realize it’s been 10 years and to realize that he didn’t get to grow up. We didn’t get to see how he would have turned out, the person he would have become,” Clara Gallegos, 18, who was a classmate of Manwill and a close friend of one of his stepsisters, told the Idaho Statesman.

“We’ve tried to remember him, and we have. The community knows who he is. Everyone knows who Robert is. People in Boise. People in Oregon. Everyone knows who Robert is. ... As long as his name isn’t forgotten, then we’re doing something right.”

New Plymouth has memorialized Manwill in many ways, from dedicating a large green swing to him outside the elementary school to raising $47,000 for college scholarships through annual art auctions. The winners of those scholarships, four of which will be $10,000, were to be announced during an April 27 celebration for the 60 students in New Plymouth High’s 2019 graduating class.

Manwill’s tragic death touched many, including Gallegos, who has decided to pursue a career in pediatric nursing. She’s already earned nursing assistant certification while still a high school student.

“I feel like if I can help one kid, or two kids, or anyone, then that’s something that I can do,” she said. “I feel like someone should have noticed (the abuse of Robert), and no one noticed.”

Investigative reports by former Statesman reporter Kathleen Kreller exposed the state’s apparent failures in monitoring Robert Manwill and his mother, Melissa Jenkins, who had fractured his baby brother’s skull and was prohibited by court order from living with the baby.

But she was, in fact, living with the baby and his legal father, Daniel Ehrlick Jr. — and the couple repeatedly hid a battered-and-bruised Robert Manwill in a closet so visiting social workers wouldn’t see his injuries, according to testimony at Ehrlick’s trial. Social workers visited the apartment several times a week while Manwill was staying with his mother during June and July that summer, but never checked him over for signs of abuse, court records showed.

The Manwill family declined comment for this story.

Miren Unsworth, administrator at the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare’s Division of Family and Community Services, said Manwill’s death was “transformative” for the department.

“It was substantial in terms of having us take a deep look at our practice, in bringing in some outside experts to help us analyze how we approach the work and then making some pretty significant modifications based off that,” she said in an interview at her Downtown Boise office last week.

At the time, Idaho was the only state in the country that didn’t have a child death review panel. That was established after the killing of Manwill.

MASSIVE BOISE SEARCH, THEN MAJOR CRIME CASE

Boise police first became aware that Manwill might be in trouble on July 24, 2009, when Ehrlick reported him missing from the Oak Park Village apartments. The complex is off of Vista Avenue, about a half-mile north of Interstate 84.

Their search for the boy, with the help of the FBI, turned up nothing after hours, and then days. That’s very unusual. The department had more than 150 missing-child reports the previous year, and most were resolved quickly.

Investigators searched apartments and cars. Dogs were brought in to scour apartment grounds. Divers searched a pond, and then it was drained. Idaho National Guard helicopters did an aerial search. Police dug up the backyard of a Boise man connected to Ehrlick and Jenkins.

Boiseans came out in droves to help, and it turned into one of the most massive search efforts in city history. The search went on for more than a week.

“There were probably four or five days in a row, I think, where we were upwards of 2,500 to 3,000 volunteers out searching vacant yards, parks. It was summertime, so all the canals were full,” Boise Police Lt. Brett Quilter, lead investigator on the Manwill case, said in an interview last week at City Hall West. “It was a pretty epic task that our patrol sergeants took on for that.”

Volunteers had to provide IDs and submit to background checks before they were sent out as part of search teams with police.

“Probably no other case in Boise history has touched so many people,” then-Boise Police Deputy Chief Jim Kerns told the Statesman in 2009.

“People wanted to get in there and show their community support. That’s what I remember, everything the community did to help this boy,” Kerns, now retired, told the Statesman in a phone interview last week.

National news outlets picked up the story, Quilter said, and detectives chased thousands of leads that poured in from across the country, including some from psychics in other states.

The boy’s body was found in the New York Canal in southern Ada County on Aug. 3. A few days before he was found, police announced that they had evidence from Jenkins’ apartment that indicated he might have been injured or the “victim of a tragic event.”

In court documents, prosecutors said that Manwill was beaten for weeks as part of a horrific pattern of escalating violence that ended with a fatal head injury. Investigators determined that a hole in an apartment wall was caused by Ehrlick slamming the boy’s head into it. Ehrlick, who weighed 277 pounds, admitted to detectives that he kneeled on the 50-pound boy’s chest more than once.

A jury found Ehrlick guilty of first-degree murder by torture and aggravated battery in 2011 and he was sentenced to life in prison. That conviction was upheld by the Idaho Supreme Court in 2015. Ehrlick, now 46, is currently at the Eagle Pass Correctional Facility in Texas.

Ehrlick hasn’t had any disciplinary offenses in recent years. In 2013 and 2014, he was written up for allegedly stealing garlic cloves and Hershey’s cocoa powder from the kitchen, and for poking his finger into another inmate’s chest during an argument, according to reports obtained through a public records request.

Jenkins was charged with first-degree murder but pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting second-degree murder in exchange for a recommended sentence of 25 years in prison without parole.

Jenkins, now 39, is being held at the Pocatello Women’s Correctional Center. She has been disciplined several times, including twice last year, for disobeying orders and manipulating staff. In a 2016 incident, she was accused of being loud and disruptive, and also threatening to beat up another inmate if she was moved to another floor. Last year, she told staff that she wouldn’t live with her cellmate or anyone else in that unit.

IMPROVING CHILD PROTECTIVE SERVICES

After Manwill’s death, the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare did an internal review of the case. A second, independent review was done by a blue-ribbon panel, which made recommendations for improvements.

Unsworth said the department brought in an expert from from the National Resource Center for Child Protective Services to look at their safety assessment practices — the way they conducted investigations. What they initially thought would be “tweaks and refinements” turned out to be a multiyear project.

“We really did a pretty significant, massive overhaul to our safety assessment practice model,” Unsworth said.

She said the previous approach was incident-based, with social workers focused on determining whether a specific incident occurred. Now they take a broader, more comprehensive approach.

“Much more comprehensive in terms of what kinds of questions we’re asking people, what factors we’re looking at and how we’re approaching working with families,” Unsworth said.

They also changed their approach to the safety assessment of children who don’t reside in the home, called “temporary child residents.” That’s what Manwill was when he was staying with his mother.

“We put forth very specific expectations of our staff for the assessment of those children who are in and out of that home, contact with them and contact with their primary caregiver in both our safety assessment process,” Unsworth said. “And then if there’s a more formal intervention and we are going to be involved with the family long-term, what that contact needs to look like on an ongoing basis.”

The other major recommendation was the development of a statewide child fatality review panel. The governor’s Task Force for Children at Risk had one previously, but it was never codified in state statute and fell by the wayside, Unsworth said.

Created through executive order, the Idaho Child Fatality Review Team started meeting in 2012. The team has a wide range of professionals, including physicians, epidemiologists, pathologists, child advocates and coroners. They review all child deaths, not just homicides.

“I think it’s a huge step forward,” said University of Idaho law professor Elizabeth Brandt, chairwoman of the independent review panel. She said the review of child deaths is critical for understanding the state of children’s health and how often they are subject to violence.

REMEMBERING ROBERT RIPPLE EFFECT

A decade later, photos, notes and other mementos of Manwill intermingle with newer items on New Plymouth Elementary School teacher Christy Norris’ classroom walls. The glass trophy case in the entryway of the school also has a framed photo of him.

His teacher and students from Robert Manwill’s second-grade class miss him as they graduate 10 years after his death.

Manwill was described by many as an affectionate boy who gave surprise hugs.

“I remember we had a birthday party, and he came up and he hugged my mother,” said Russell Cope, 18, who helps out at annual Manwill-inspired fun runs. “I thought that was cool, how you can just hug someone you don’t even know.”

The details of the summer that Manwill disappeared are something of a blur to Norris now, though she vividly recalls getting on a bus with others from New Plymouth to go help search for the boy.

When school resumed in the fall, she consulted a school counselor about talking to Manwill’s 7-year-old and 8-year-old classmates about what happened. They kept it simple.

A half-dozen of Manwill’s classmates recalled knowing something bad had happened, but they didn’t fully understand exactly what it was until years later. As they got older, more details were shared during annual informational sessions about child abuse.

“These kids literally grew up with every year being reminded of this thing that happened, and what we can do as a community,” Norris said. “Who knows? You don’t know what kind of ripple effect you have on these peoples’ lives, these kids’ lives, but we do know that they’ve all paid attention.”

Taiylor Myers, 18, plans to become a teacher. She said she took some inspiration from Norris.

“I can’t go to every student’s house and make sure their home life is right,“ Myers said. “I would just want to be there for the kids, while they’re at school, and make sure that their school life is good ... carrying on the legacy of her (Norris).”

Emily White, 18, said the community came together in a positive way after Manwill’s death.

“I’m obviously not happy that this happened,” White said. “But I’m glad that we have this sense of awareness now in the New Plymouth community, and that we’re trying to make an effort to prevent this in the future to any of our students.”