'I got to know the enemy'

Five years as a prisoner of war gave Bob Chenoweth plenty of time to think about the consequences of war

Since this story originally ran on Memorial Day 1996, Bob Chenoweth has moved to Moscow. Now 67, he is still curator at the Nez Perce National Historical Park in Spalding, but no longer serves as cultural resource manager.

Chenoweth had an opportunity to return to Vietnam in 2014. He wanted to visit some of the historical sites he didn't get a chance to see as a POW; he also re-visited the "Hanoi Hilton" prison grounds, which is now a museum.

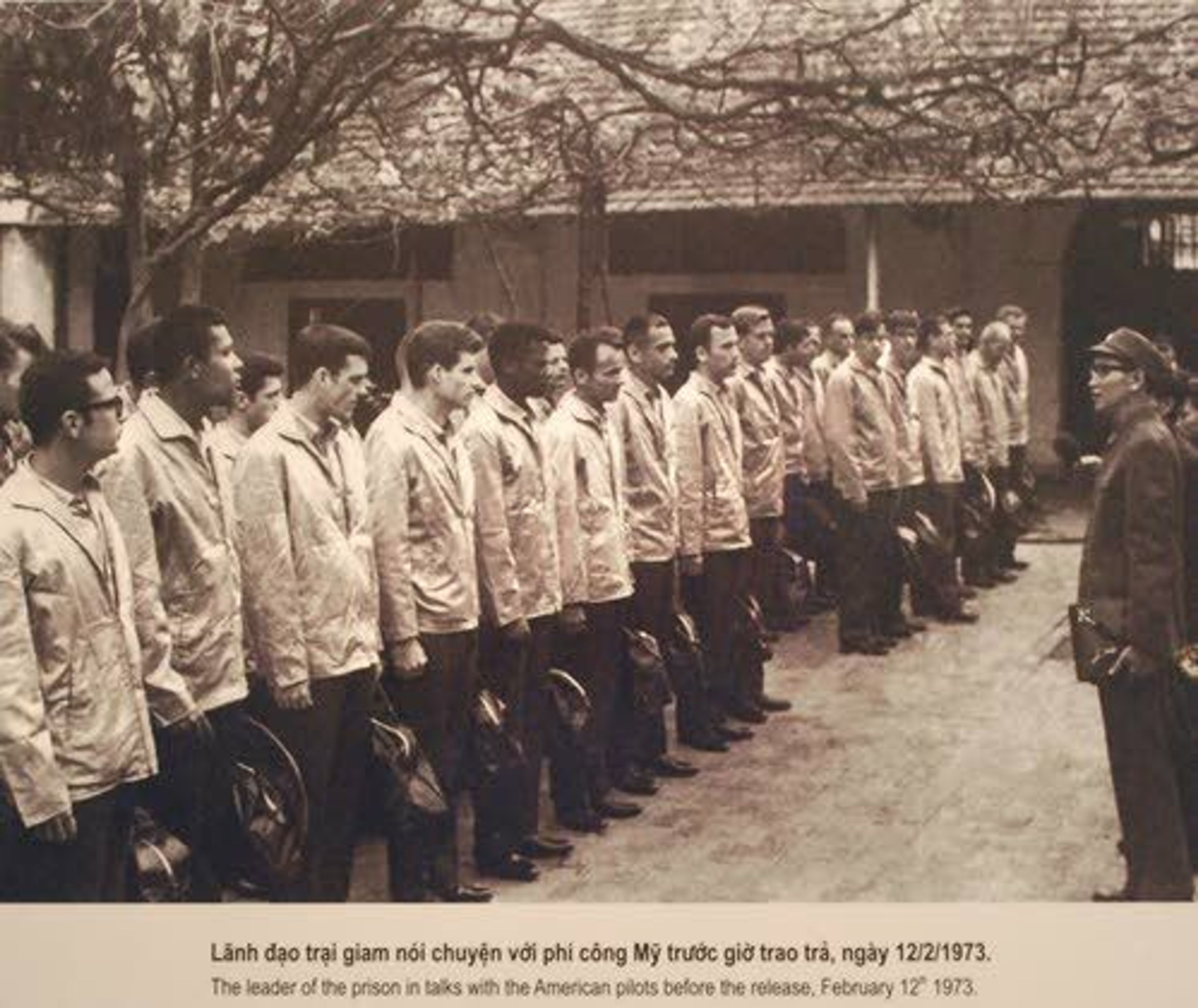

"They had a photo on the wall showing my release group, March 15, 1973," he said. "I recognized almost everyone. I took a photo of that. There were a number of American, British and Australian tourists there. I did an impromptu talk about my experience."

During the trip, he had a chance to visit friends in Hanoi. He also met someone who was a boy during the war.

"He lived about three blocks away from the camp," Chenoweth said. "When he was told there were American prisoners down the road, he remembers sneaking over the wall to see them. There was this whole other world going on outside the camp that we never knew about."

No one spoke as the bus full of American prisoners of war drove away from the Hanoi Hilton.

"It was a little melancholy," remembers Bob Chenoweth of Clarkston, who spent the last four months of his five-year captivity in the famed North Vietnamese prison.

"It's not that I wanted to stay," said Chenoweth, who was just 25 when he was released, "but I was leaving something that had become comfortable and I was going to something new.

"(Vietnam) was the place where I grew up."

His captors were no longer the enemy. "I'd learned that a long time ago," he said.

The hours of solitary thought and more hours of intense discussion with his fellow POWs taught him to think, Chenoweth said, especially about the justness of the war.

"Before, I didn't think. I just went along."

He pondered responsibility and choices and the consequences of the decisions one makes. "It forced me to think about what I'd done and to (take an analytical) look at American history," he said.

He came to an important realization about freedom and the war in Vietnam.

"Now I cherish freedom with a little 'f.' Freedom with a big 'F' is the thing that gets people into trouble."

Chenoweth is curator at the Nez Perce National Historical Park's visitor center in Spalding.

He acknowledged he was active in the anti-war movement after his release in 1973. His outspokenness had repercussions.

Today, he is willing to talk about his experience, but not for political reasons. Instead, he offers his story in observation of Memorial Day.

He was only 20 and a U.S. Army soldier from Portland, Ore., starting his second tour of duty when he was captured. His helicopter was shot down near Dong Ha Feb. 1, 1968, during the Tet Offensive.

It couldn't have been more than 45 seconds from the time the Huey first took enemy fire until the chopper was smashed into the sand, burning and ready to blow.

But to Chenoweth, it all happened as if in slow motion. He remembers returning fire on the invisible enemy in the bushes below, about 400 rounds, and turning to see the helicopter's windshield shatter in the face of his pilot.

He saw the ground coming up at him and the next thing he knew, he was on his hands and knees about 40 feet from the crash.

Within an hour, Chenoweth and five fellow soldiers were Viet Cong prisoners of war.

Surrounded and outnumbered, the only thing to do was surrender. "If we started shooting, we'd all be dead," Chenoweth said.

But one of his companions protested. "Joe said that wouldn't be playing the game. I said, Joe, this is no game.' "

The first week was spent on the move. On foot. With no shoes.

They took to walking in streams, where leeches latched onto their feet. Later, the prisoners were given Chinese tennis shoes, but they were too small. They wore them anyway.

There was a seven-day trek through heavy jungle. It was cold and their only food was rice balls wrapped in leaves.

The group finally stopped at a house where they were given hot rice and broth.

"I ate some serious rice that night," Chenoweth remembered. "Eleven or 12 bowls."

Much later, another soldier who'd stopped at the same house told him how the people still talked of this one American who "was a real pig."

"They were talking about me," he said with a laugh.

Finally, the walk ended at a heavily traveled dirt road that Chenoweth realized was the Ho Chi Min Trail. The group, now numbering about a dozen, rode trucks at night for two weeks until they were north of the 20th parallel. Then they rode both day and night.

The first camp was called Portholes because each of the tiny rooms in the barracks had a small round window. There was space only for a rice straw sleeping mat and foot stocks for those who disobeyed.

He received his Vietnamese name there, Che, taken from the first three letters of his name.

At Portholes, the prisoners had a garden and daily chores to do. Sometimes at night they would carry supplies, such as sugar, rice and huge woks, which looked like enormous turtle shells on their backs, to nearby villages.

There also was lots of time to do nothing but think.

"I used to build models in my head," Chenoweth said. He had enlisted in the Army because of his fascination for aircraft, and as a soldier he had been busy documenting details of the war machinery.

"This was a helicopter war. ... The strategy and tactics were different because of helicopters, and I was in the middle of it," he said.

After the war, Chenoweth published a book, "Army Gunships of the War," and has written numerous magazine articles on the subject.

On the supply treks, villagers would come out to watch them walk by and children sometimes would throw dirt at them. But people also offered them candy and cigarettes.

Chenoweth said he was never really interrogated. The Viet Cong mostly asked him biographical information. "They (already) knew more about what we were doing than we did," he said.

"The question from them wasm 'Why are you here?' It became a huge ideological struggle."

If a soldier said it was "to fight Communism" the Viet Cong would ask, then why not fight it at home or in Cuba?

"They were messing with our minds."

He was never tortured, but he did fight with the guards on occasion.

"You could choose to be belligerent and you could choose not to be. When I did, I got my ass kicked," he said.

They stayed for about a year in Portholes until moving north again. They stayed at the next camp, still in the countryside near Son Tay, from late 1968 until 1971.

Then came the Son Tay commando raid by the U.S., and "we went downtown" to Hanoi, Chenoweth said.

At The Plantation, old French company barracks, they again settled into a routine. There was gardening and full-sized pot-bellied pigs to take care of. The prisoners gave each other lessons - Chenoweth taught drawing - and they were taken on "field trips" to museums, historical sites and the theater.

The country's best performers would put on shows at the prison.

"It was nice to be able to see all this," Chenoweth said. "They wanted us to understand who they were as people. ... to (understand) their long history and how they were different from the Chinese."

Sometimes, on holidays, the prisoners got beer. They developed a system to pool the bottles on a rotating basis so when it came your turn, you'd get four beers and a buzz instead of just one beer.

Toward the end of 1972, the U.S. bombing of Hanoi intensified. "They told us the morning of Dec. 21, 1972, they would probably move us. We were real bummed because we had planted watermelons."

One prisoner, an agriculture major from Cal-Poly, suggested growing melons as a way to use all the pig manure the pot-bellies produced.

"The watermelon patch was looking pretty good in December 1972," Chenoweth said.

By the time the group got to the Hanoi Hilton, the men knew the end was near. "We knew the (peace) agreement was coming," he said.

On March 15, 1973, he was one of the official 566 prisoners of war released by North Vietnam.

Chenoweth came back from Vietnam with many mementos. He still has the tin rice bowl, decorated with a pink flower, he carried from camp to camp, and his two sets of chopsticks - one set for every day and the other for holidays.

He has his black pajamas, his "Ho Chi Min sandals" (made from rubber tires), his rice straw sleeping mat, and a "souvenir" tea set given to him by his captors upon his release.

Chenoweth also brought away two very different perspectives of the war in Vietnam.

The first year he spent flying over and gunning the enemy, faceless and elusive in the bushes below.

"You never knew if you killed," he said. "And then I'm living with them

"Now I look at it as an opportunity," he added. "The lesson for me was that people are very similar. I got to know the enemy."

Chenoweth said he was more interested in learning about the people than most others. "I guess it depends on how open you were to listening. Even in South Vietnam, I was more interested in knowing the place where I was."

The contrasting experiences opened his mind, Chenoweth said. "I now think about things in a way I never did before. It made me wiser. I learned there are a lot better ways to solve differences than kill people."

He considers himself lucky to have had the time to work out what he'd been through.

"What happened to (other servicemen and women), they went through all this stuff and had questions about what they did and got no answers and were cut loose. They got no training to help them deal with it. Some people said it was OK and some said it was not OK, but they never had a chance to think about it themselves.

"But I had five years to think about it. We (POWs) discussed it, with no bullshit war stories."

"It's like a lot of things," Chenoweth reflected. "Anytime you're in a situation you consider bad, there can be good in it." n