Golden anniversary of a troubled wedding

50 years ago, the city of Lewiston annexed the Lewiston Orchards, a decision that some residents still bemoan

The Lewiston City Council unanimously annexed the Lewiston Orchards into the city limits 50 years ago today, taking many of its residents kicking and screaming along the way.

It was a lengthy outburst that culminated with a recall election a year later that cost six members of the seven-member council their positions. And even though a subsequent deannexation vote failed by a wide margin — largely because of fatigue over the issue — echoes of the animosity that dominated the disagreement still reverberate today.

“It was like two communities,” recalled 83-year-old Sharrol St. Marie, a lifelong Lewiston resident and community volunteer whose late husband, Duane St. Marie, won election to the city council on the same ballot as the 1971 deannexation vote. “There was downtown, and there was the Orchards. And I’m really happy that they joined together.”

Barbara Willows wasn’t so happy. Her late husband, J. Dan Willows, was one of the leaders of the anti-annexation Orchards Community Project, and she remembers residents were downright furious over the prospect of being forced into the city.

“The city was going to come up and basically take over the Orchards and increase our property taxes significantly,” said Willows, 82, who lived on Burrell Avenue at the time and now lives in an unincorporated part of Asotin County.

And there were no guarantees that Orchards residents would benefit very much from joining the city, Willows said, noting that Nez Perce County was already doing a good job of providing services like road maintenance. The only thing Lewiston could add was police protection, but crime was virtually nonexistent back then, and the sheriff’s office would have added patrol deputies as the Orchards grew, she said.

“There’s nothing the city could have given us that the county couldn’t have given us over time,” Willows said. “I don’t know that belonging to Lewiston made the Orchards any different.”

The mistrust ran deep

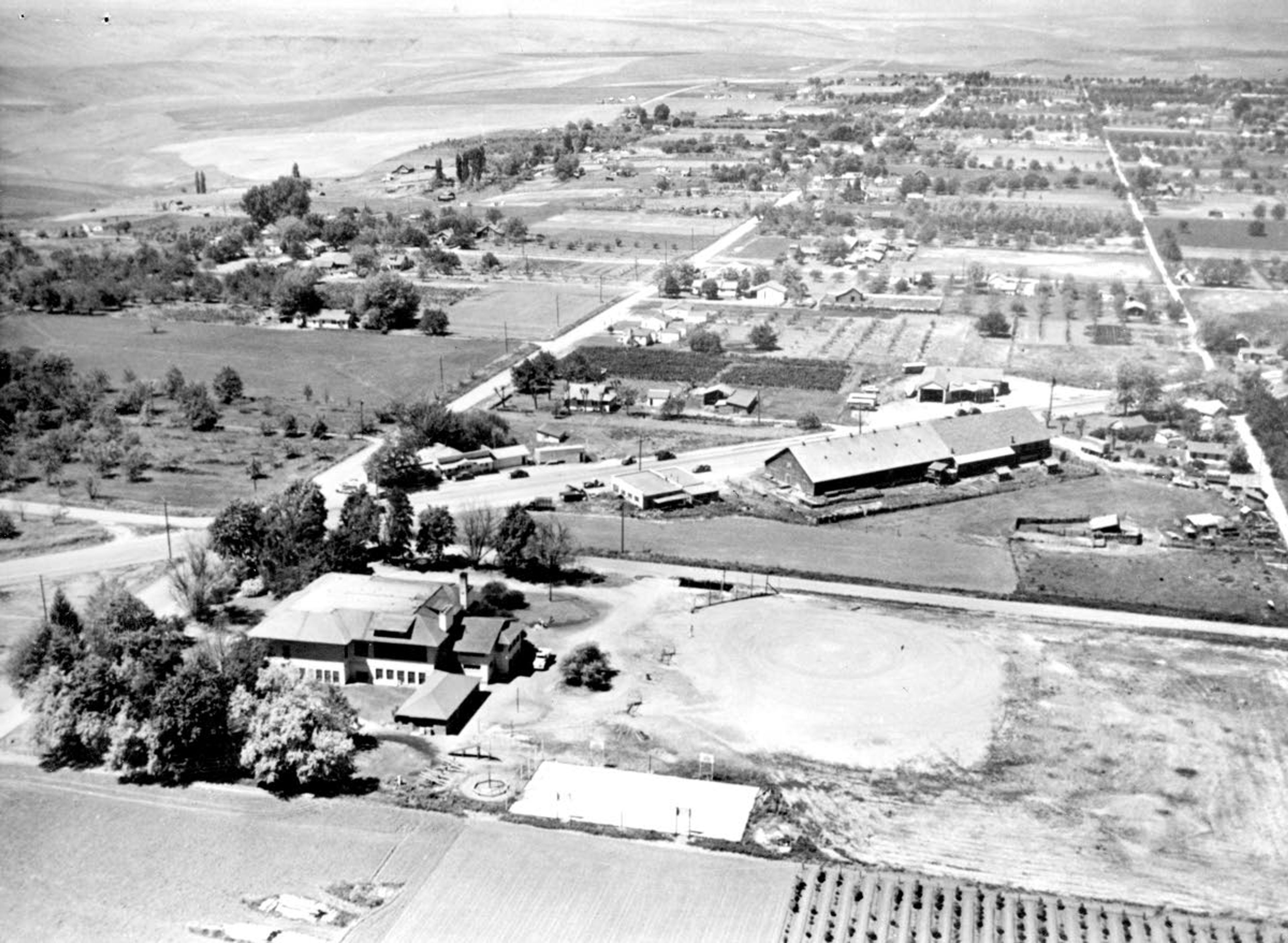

Some would say the Orchards grew up organically, while others might attach the word “haphazardly” to its development over the years. St. Marie called it “a happening. There was no planning. It just happened.”

But whatever it is called, residents of the time prided themselves on the community they built and carried a sizable chip on their collective shoulders throughout their resistance to city governance.

Annexation had been a topic for decades before it actually happened. Orchards residents actually asked to be annexed by the city in 1949, according to a statement by the late Irving “Kelly” Kalinoski in a 2005 Lewiston Tribune story. Kalinoski was possibly the most cantankerous force in the Orchards Community Project and recalled that the city declined because “it didn’t want the problems.”

That changed by the late 1960s, however, when the Lewiston City Commission — a precursor to the city council — began to actively pursue annexation. Commission Chairman Paul H. Wise appointed an annexation study group in 1966. In 1967, the commission asked its legislative delegation to introduce a bill that would alter the old city charter to give it the same outright annexation powers held by other Idaho cities.

The charter gave Lewiston broader powers in some cases, like the ability to raise property taxes above the 3 percent cap enshrined in state law. But the charter also stipulated that a majority of the residents in an area facing annexation could halt the process with a petition recording their objections. State law, on the other hand, would allow annexation without a vote or other form of input from the residents.

The Legislature declined to get in the middle of what Tribune Opinion Page Editor Bill Hall called a “family fight.” So in January 1968, Wise declared the commission would do everything in its power that year to consolidate Lewiston and the Lewiston Orchards under the old charter. City finances were the main motivation behind his argument.

“The state gasoline and liquor funds returned to cities are doled out on a per capita basis,” he said. “We only get in this area about one-half of what we are entitled to. The sooner we get this started, the sooner we get it accomplished. It has to come. We might as well get in gear.”

Warren Watts, now 86, was the city engineer at the time. He backed annexation and gave Wise credit for charging ahead.

“The city government thought it had to be done sooner or later,” Watts said. “So they took the bull by the horns and went ahead for it.”

Before the month was out, however, organized opposition had arisen. Kalinoski proposed the formation of a separate city called “Orchards” that would incorporate the portions of the Lewiston Orchards Irrigation District east of 18th Street. He specified that area because state law prohibited the incorporation of a new city within 3 miles of an existing city with a population larger than 10,000.

Watts knew Kalinoski well, and they got along even though they were on opposite sides of the annexation issue. He recalled Kalinoski as a formidable adversary with a flair for dramatic gestures.

“Irv, he was right there sitting at all the council meetings,” Watts said. “I remember one time he came down to city hall and put a big log right there in the doorway.”

Kalinoski had inscribed the 15-foot-long log with his objection to annexation and his signature as his official protest. The city clerk accepted it as valid.

“It was an interesting time,” Watts said, chuckling. “I enjoyed Kalinoski. I would sit there and argue with him and other people, but I think we respected one another.”

Kalinoski’s movement to create a new city didn’t gain much traction, however, possibly because it would have created another layer of bureaucracy in the county.

“As a Thain Road businessman said yesterday, ‘We would end up pouring money down two rat holes instead of one,’ ” Hall wrote in a Jan. 10, 1968, column. “If there is one thing this community doesn’t need, it is another government entity, another taxing unit on top of taxing units. There should be consolidation, not the creation of two cities where there could be one.”

Then the Nez Perce County Commission dealt the final blow to the prospective city of Orchards by denying Kalinoski’s incorporation petition in March. That decision emerged shortly before the end of a period given to Orchards residents to register their protests to annexation. And once the city realized those protests could very well amount to a majority and halt the annexation move, officials abandoned that first attempt.

A second attempt in July ended even more abruptly when the Orchards Community Project filed 4,260 signed protests, which appeared to be a sufficient number to invalidate annexation. City officials were accused of trickery when they tried to count individual cemetery plots in the Orchards as pieces of property, thereby increasing the number of protests needed for a majority. But the courts slapped down that attempt, and annexation with it.

Ed Campbell, 83, lived in the Orchards on Cedar Drive at the time. He didn’t oppose annexation, but heard many of his neighbors’ fears that the rural atmosphere would go down the tubes if they were absorbed by the city.

“They were opposed to the annexation, a lot of them simply because they had property and cows and pigs and whatever,” Campbell said. “There were no restrictions, so they were scared all those things were going to change.”

Wise made the rounds, pledging that the status quo on issues like animal rights would be maintained if annexation went through. St. Marie said the mistrust ran deep, however.

“I was always sorry that they had such an animosity toward this, because I thought it would benefit them,” she said. “It’s hard to tell people who have grown up in the country that they’re going to have to follow rules, and that was kind of what happened.”

There were several community organizations that arose around the conundrum, and one that was born in the summer of 1969 would end up playing the crucial role that led to annexation. The Municipal Unity Committee supported annexation, and mounted a petition drive to force an election to drop the old city charter. If successful, it would put the city under the general codes of the state of Idaho. And since those laws didn’t provide for a protest procedure against annexations, the city would be free to annex as it pleased.

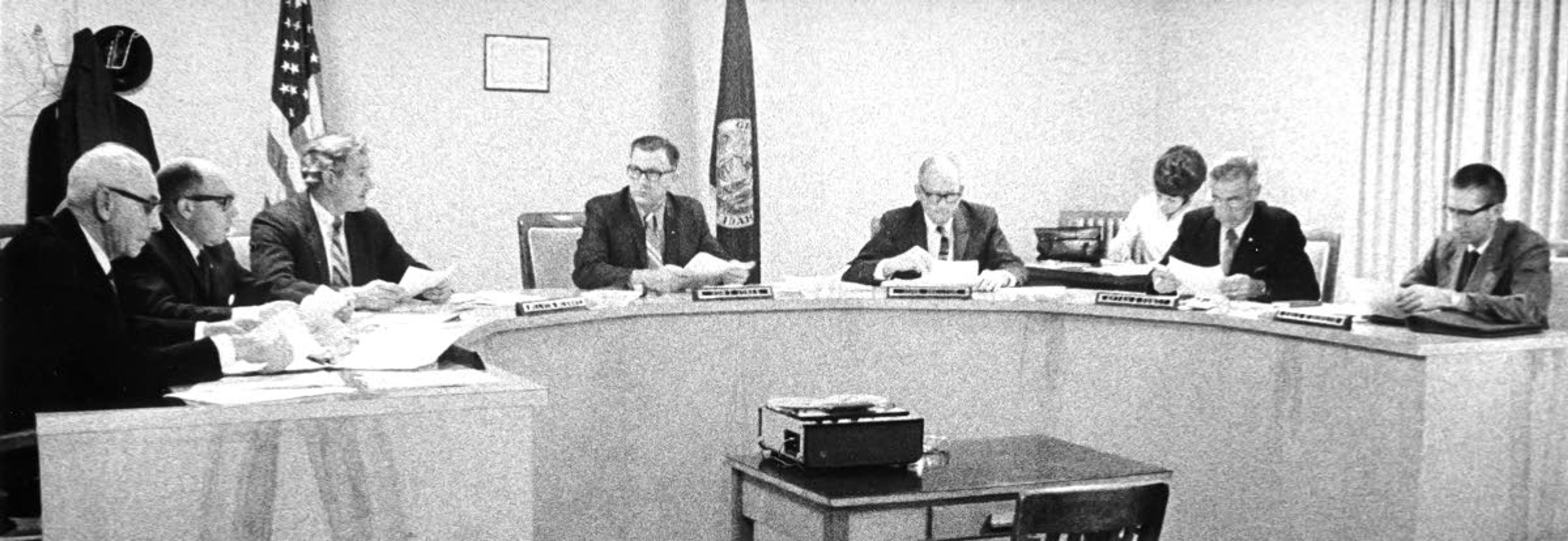

Voters officially repealed the charter on Oct. 14, 1969, 1,591 votes to 329. The city commission officially became the city council, and its members held the successful annexation vote just two months later. Lewiston and the Lewiston Orchards were officially one city.

Willows said that even though killing the charter made it easier for the city council to annex the Orchards, those who opposed annexation chalked it up as a victory, because it meant the city’s ability to raise property taxes would be capped at 3 percent per year by state law.

“We figured that we won, because the charter gave them the ability to go up to even higher taxes,” she said.

The fallout

That momentous occasion wasn’t the end. Minutes after the council waived the usual three readings of the annexation ordinance and passed it at the same meeting, the Orchards Community Project announced its recall effort.

One of the steadfast complaints of the anti-annexation crowd was over the procedures used to pursue unification, and that it had never been put to a vote. Orchards Community Project President Howard G. Jeppson again pointed that out after the council approved annexation.

“How many votes have ever been cast by the people of Lewiston directly on the question of annexation?” Jeppson asked. “This city council has repeatedly denied its own citizens even the courtesy of an advisory ballot on this question.”

Orchards Community Project members tried to get the Legislature to change the state annexation laws, but their bill never made it out of committee. They also pursued a court challenge of the annexation ordinance over the next months, even putting up their homes as collateral for loans to cover their legal fees, Willows said.

“When you start hocking your house, you know they’re taking it seriously,” she said wryly.

The city also went to court to challenge the legality of the recall election. Both sides lost, and the Orchards Community Project put up a slate of candidates to challenge the sitting council in the recall. And on Dec. 1, 1970, Melvin R. McGary, Bryan B. Bundy, George Giese, Dale Gordon, Ron F. Jones and Donald K. Mellen took the seats of Mayor Wise, Gunder W. Kjosness, Robert W. Olin, Melvin W. Stewart, Paul E. Wood and Guy O. Spurgeon. Councilor John J. Skelton was the sole survivor.

Some division remains

The wounds between the Orchards and downtown seemed to scab over after voters rejected deannexation a year later. But they never truly healed. In one example, Kalinoski — ever the gadfly — again took his gripes to the city council in 1982. According to a report in the Tribune, he said Orchards residents hadn’t gotten much out of the bargain in the intervening 13 years.

“The city hasn’t done a damn thing up here — except for alleys — since we were annexed,” he said in a charge that the council strenuously denied.

City Councilor Marlene Schaefer essentially told Kalinoski to stuff it, noting the city street department had tried to grade the sides of the street berms in the Orchards.

“But the street superintendent told me he had so many complaints about the dirt and the inconvenience that he had to stop,” Schaefer said. “So if you want your road berms shaved, you’d better keep your mouth shut.”

Watts said pouring money into the Orchards simply wasn’t an option.

“The people at the time, once they got annexed, they said ‘Well, give us new streets; give us new sidewalks,’ what have you,” he said. “Which is, of course, impossible unless they pay for it themselves.”

Watts added his thought that the slow growth in Lewiston over the last 50 years has spared it from frequent demands for massive infrastructure improvements.

“We’re not getting swamped,” he said, bringing up the rapid growth that has emerged in other Idaho cities. “We’ve still got our headaches like traffic conditions, but they’re nothing like Coeur d’Alene or other larger communities.”

St. Marie agreed that divisions between the high and low areas of Lewiston have remained. She said it is partly because LOID wasn’t also incorporated into city government.

“I was always disappointed that they didn’t get the water system straightened around at the very beginning,” she said. “That would have helped a lot. Otherwise, it’s just a very nice community.”

Mills may be contacted at jmills@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2266.