Flying old school

Couple works to open vintage aircraft museum at Lewiston-Nez Perce County Regional airport

All Gary Peters has to do to sit in a plane that Charles Lindbergh once flew is to venture into his hangar at the Lewiston-Nez Perce County Regional Airport.

That's where Peters keeps his growing stable of more than 15 airplanes. Almost all are vintage. Many have ties to the Golden Age of Flying in the 1920s and '30s, where airplane races often dominated national headlines and pilots were American heroes.

Peters and his wife, Jillyn, are so convinced of what the public can learn from the collection that they are working on plans to display the planes at a 20,000-square-foot aviation museum scheduled to open next year at the Lewiston airport.

"We love the generation and the people. It's the history," Peters said.

Flying is where the couple spend their spare time. They budget much of their discretionary income for the hobby they can afford because of their ownership in Peters & Keatts equipment, a Lewiston-based business that sells and rents heavy trucks and equipment for construction.

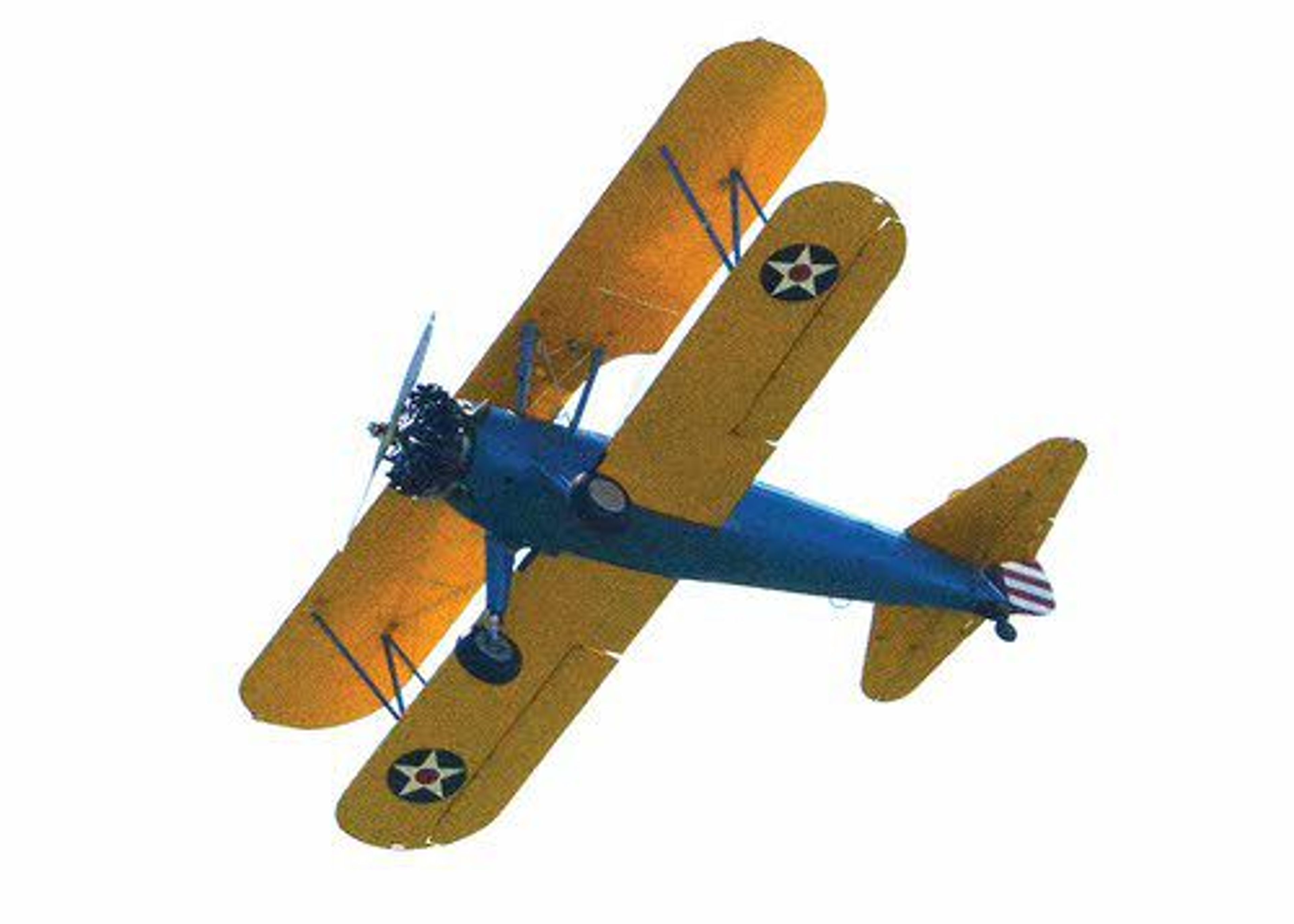

Although they hesitate to play favorites, their 1929 Stearman Model 4E Jr. Speedmail is the crown jewel. It's a biplane with two open-air cockpits that offer a glimpse into how society functioned in the late 1920s.

Lindbergh completed the first solo transatlantic flight in 1927, taking off from Long Island, N.Y., and landing in Paris 331/2 hours later. The time Lindbergh spent in Peters' Speedmail was a matter of luck. The historic pilot was perhaps the nation's biggest celebrity after he returned. Anywhere he went, people begged him to fly their planes, Peters said.

On April 2, 1930, Lindbergh flew the plane for 30 minutes from Burbank, Calif.

"It's in his log book at Yale," Peters said.

The connection to Lindbergh isn't the only reason the Speedmail is special. It's one of seven of the planes that have survived and among only five that still fly.

Typically, it would have been flown to make sales calls at gas stations on behalf of the Richfield Oil Co. The planes provided the speed the staff needed to make a required 60 calls per month in California, Oregon and Washington.

Peters takes the responsibility of owning it seriously. He purchased it from a female Chicago-area pilot who had worked for Kermit Weeks, a wealthy and prolific collector of vintage planes.

She didn't have the plane listed and sought him out, specifying unwritten conditions that are common in the pay-it-forward culture of private aviation, Peters said. "She wanted the airplane to be flown and enjoyed by children."

There was something else, too. To pay for the Speedmail, Peters sold two World War II-era Boeing Stearmans. The planes were used during the war to train most pilots. He and Bill Strange, Peters' full-time mechanic, had restored the planes after rescuing them from a Hood River, Ore., museum, replacing the instruments, redoing the electrical, oil and fuel lines and covering some explicit art on the noses.

Peters made sure the asking price was reasonable enough that 9/11 hero Heather Penney could afford one of the planes. The then-lieutenant was one of the nation's first women fighter pilots and one of two officers assigned to ram their fighter jets into a Boeing 757 over Pennsylvania before it hit its intended target. Penney didn't hesitate to undertake what amounted to a kamikaze mission, but survived the day because the passengers brought down the terrorist-controlled plane themselves.

Another one of Peters' specimens has even more direct ties to the heritage of women in the military. It's a 1932 Waco UBF-2, once owned by Betty Gillies, a friend of Amelia Earhart. Gillies was the first woman to qualify for the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPS). She delivered fighter planes to bases in the United States and Canada during World War II.

Like the Speedmail, it's rare. Only 16 were manufactured and fewer than 10, including Peters', is in good enough shape to fly. The plane was restored by men who are well-known for that kind of work in aviation, Woody Woods and his sons, Chris and Scott Woods, Peters said.

It initially went to an owner on the East Coast, but when that man was ready to sell he went to Scott Woods, asking who he would trust with the functional artifact.

The Woodses sought him out, Peters said. Chris Woods, a Hollywood heavy hitter who helped film the movie "Forrest Gump," delivered the plane to him and gave him a scrapbook of the journey.

"We haven't met a person in antique aviation we haven't fallen in love with," Peters said.

That's not Peters' only Hollywood connection. His 1941 Ryan PT-22 is the same type of aircraft Harrison Ford crashed on a California golf course in 2015. Peters credits the "Stars Wars" actor with saving lives as he piloted the notoriously finicky aircraft to the ground, landing it upright and largely intact.

Many of the 17- and 18-year-old cadets who trained in the Ryan fared much worse, dying before they ever saw a German or Japanese fighter.

The designer was Claude Ryan, who invented a sport trainer for pleasure flying that was well regarded. The Ryan PT-22's issues surfaced when it was retooled for war with a thicker skin, a more reliable engine and tougher landing gear - modifications that shifted the center of gravity and required the wings to be re-angled to compensate, Peters said. "If you make a sharp turn slow ... at a low altitude, it's not going to work out."

Those qualities stand in contrast to the Boeing PT (Primary Trainer) Stearman. More than 12,000 were manufactured. They had a reputation for being just as forgiving as the Ryans were temperamental.

It is the plane he most often uses to give rides for charity since it offers the open-air experience with safety. "They're the most well-known biplane in the world," Peters said.

As much as Peters enjoys introducing the public to flight, his wife and two preschool-age daughters are his favorite passengers.

They easily fit into the Speedmail wearing flying suits, goggles and head gear.

The couple enjoy talking about one of the dates they went on before they married. They flew from Lewiston to the Washington coast, where they landed on the beach, dug their limit in razor clams and then attended a vintage plane show before heading home and watching the sun set behind Mount Rainier.

The great thing about open-air cockpits is how you can smell the air and feel the wind on your face, Jillyn Peters said. "It's probably the closest thing you can get to flying like a bird. It's pretty exhilarating."

He, too, can't get enough and is always seeking out the next thing. It might be another plane, information about maintenance or more training so he can push the envelope of one of his planes without sacrificing safety.

At some point, he'd like to own a P-40 Warhawk. It's an aspiration so expensive he'd have to sell all the planes he owns to afford it. But that doesn't stop him from contemplating what that might be like.

He admires the patriotism and entrepreneurial spirit the single-engine, single-seat fighter represents.

"It fought in every theater of World War II," Peters said. " ... It's not a Rolls Royce. It's a 100-percent American-made fighter."

It was manufactured by Curtiss-Wright, a company still in existence today that traces its founding back to Wilbur and Orville Wright, who flew the first 12-second flight at Kitty Hawk, N.C.

The planes were the most numerous American fighters during the war, and also used by the British and French. They were based on a design that was already in production, something that allowed them to be delivered faster and at a lower price even though, unlike competitors, they hadn't been developed with the help of a military contract, Peters said. "(They) did it as a business."

Keeping these airplanes in front of the public in his planned museum is an important way to help Americans remember the bravery, determination, innovation and grit it took to win World War II, and perhaps inspire them to be more like the heroes from those times, Peters said.

"People don't realize what people sacrificed for our freedom."

---

Williams may be contacted at ewilliam@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2261.