Excellence in Indianness

Nez Perce musicians developed a passion for jazz early on, and then traveled the country to play music and try to quash stereotypes

Most might not associate jazz music with American Indian culture - stereotypical images tend to come to mind first.

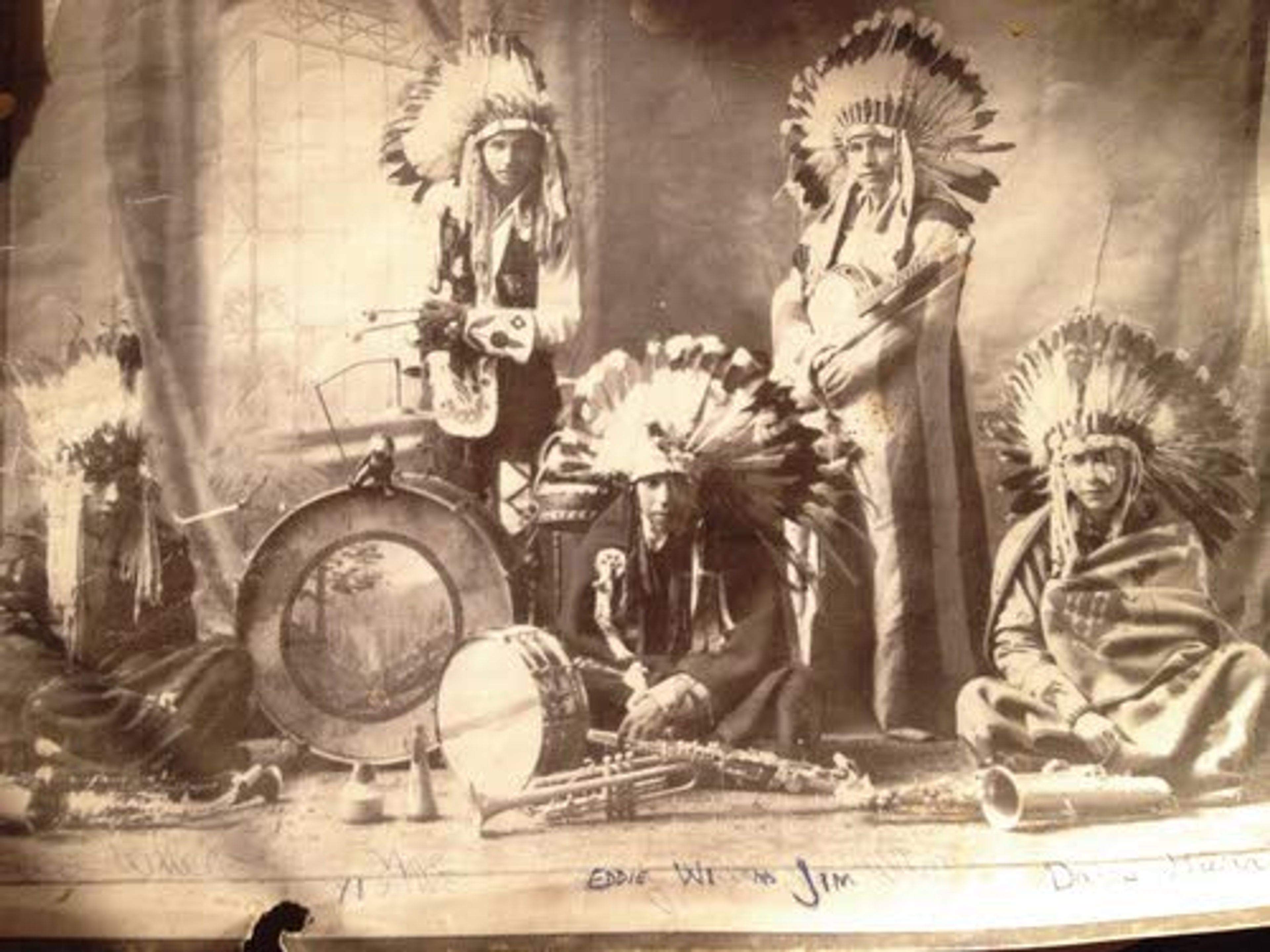

But starting as early as the 1920s, Nez Perce tribal members in Lapwai formed their own jazz bands, including one called the Nezpercians. They traveled hundreds of miles to play wherever they could get a gig, spreading their culture and love of jazz.

In fact, they jammed with Lionel Hampton in Portland, Ore., in the early 1930s during what the daughter of one band member described as a "discrimination sleepover."

Hampton, the namesake for the University of Idaho Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival, which begins Wednesday in Moscow, is known for being one of jazz's first vibraphone players and a legend in the music industry. That had little sway in 1930s America for a black man trying to find lodging.

Veronica Mae Taylor of Lapwai, daughter of Harry Pete (Fox) McCormack, who played the drums for the Nezpercians, said her dad's and Hampton's groups played at a night club in Portland during the same week and ended up connecting with one another.

"Well, it got to be late at night and nobody had made arrangements for (Hampton's band) to stay in a motel or anything," Taylor said.

Hampton and his band discovered they were expected to sleep on the floor of the nightclub. So the Nezpercians invited them to stay in their rooms, and they became fast friends.

"They jammed it up together, not even for a dance or anything. They were just playing around," Taylor said.

Hampton, who died in 2002, and McCormack remained in contact, meeting again years later at the jazz festival in Moscow, Taylor said.

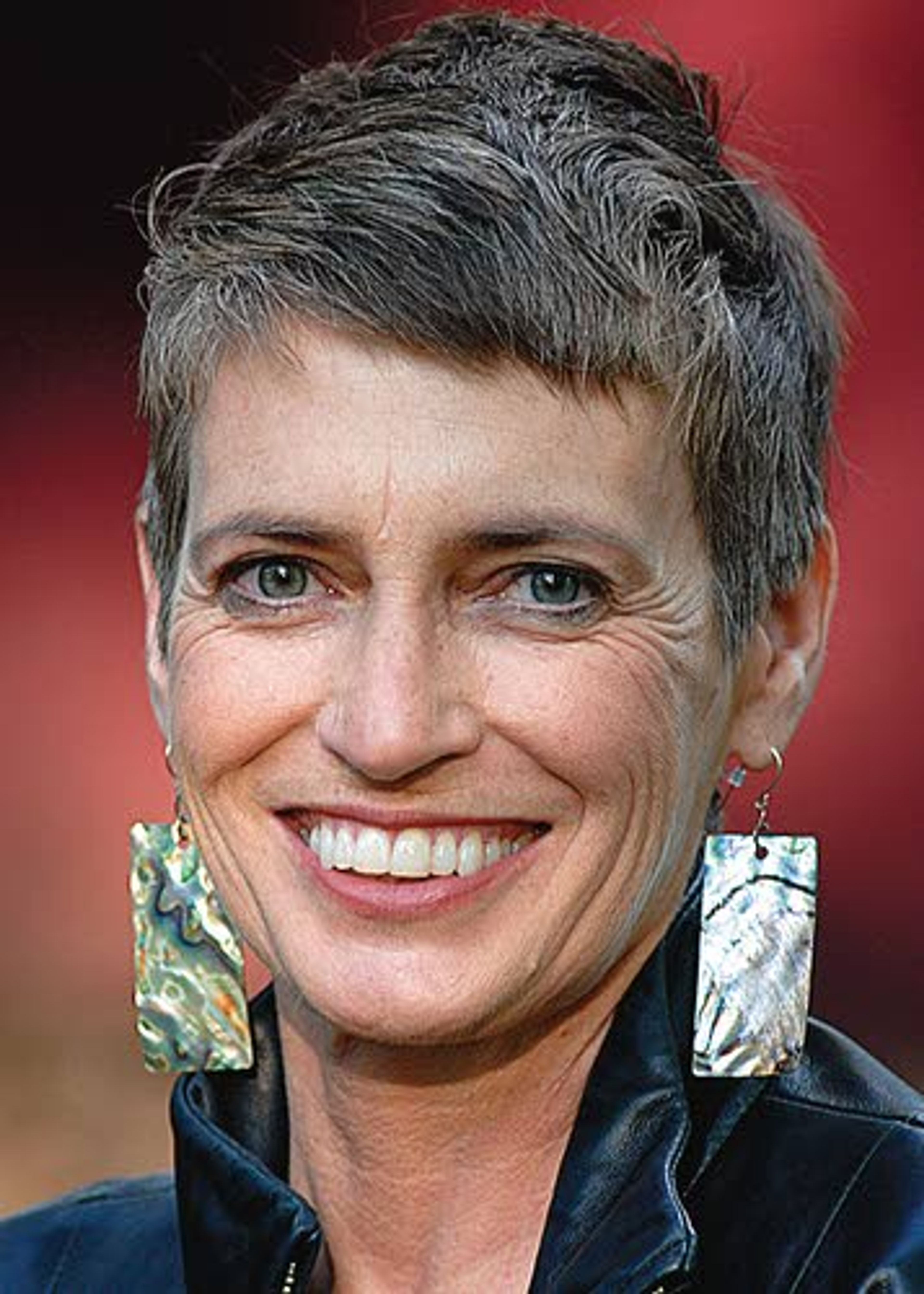

The story about Hampton is included in research conducted by Jan Johnson, American Indian Studies coordinator for the University of Idaho. Her article, titled "Performing Indianness and Excellence," was published in "American Indian Performing Arts: Critical Directions," which is available at Amazon.com. In it, Johnson details stories like the Hampton meeting and the attitudes felt by McCormack and others during that era.

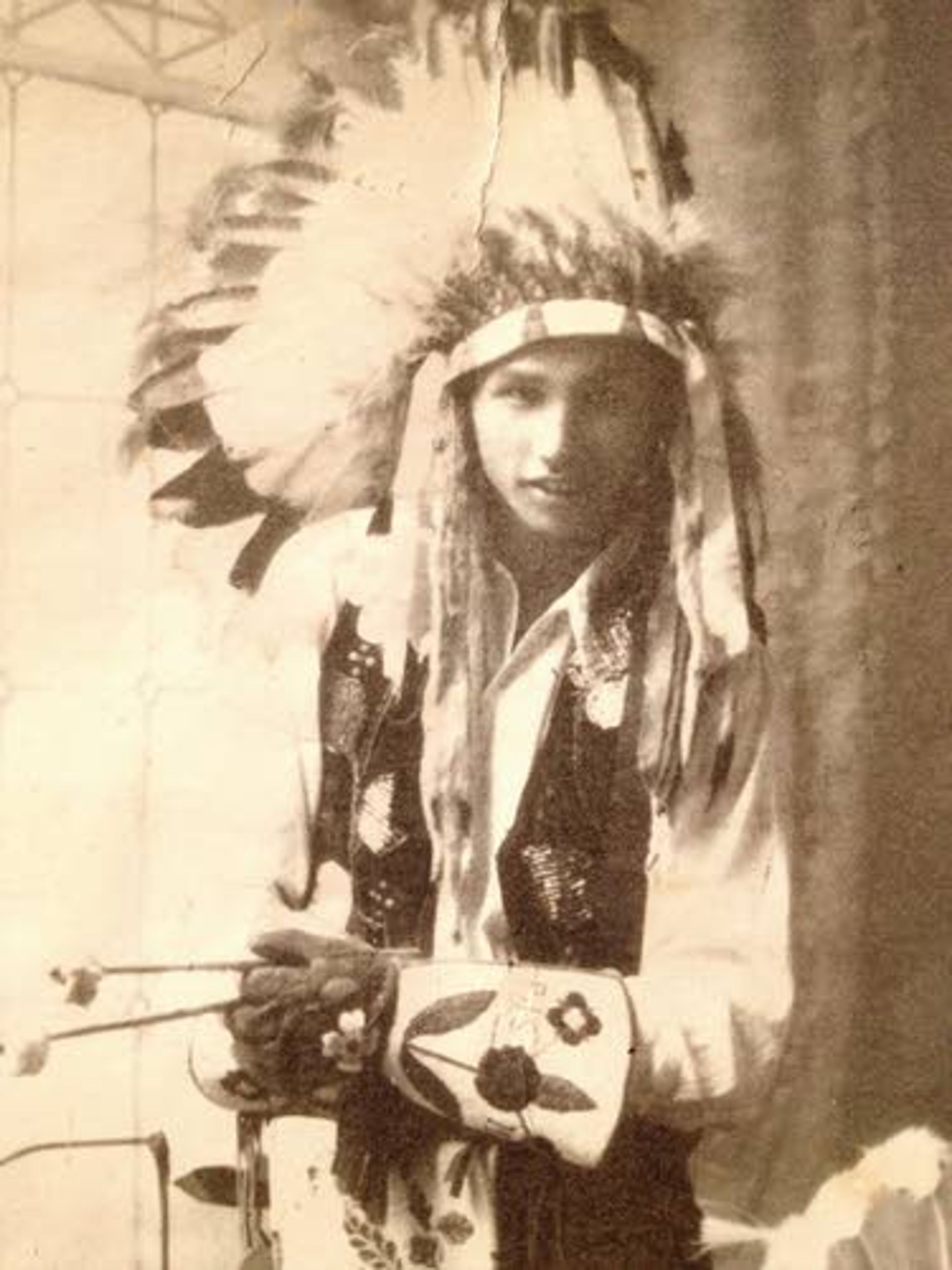

She wrote that music played a primary role in historical attempts to assimilate American Indians into white culture. Using brass and marching bands to teach "discipline" was a large part of boarding schools at places like Fort Lapwai, the federal installation that existed on the Nez Perce Reservation until 1863. But apart from the controlling aspects of it, music also provided a way for the students to "resist and survive the schools' ideologies, which included outlawing Indian dress, language, music and ceremony."

Johnson wrote that McCormack, who grew up on the reservation, received his first set of drums at age 10. He and his cousin, Titus White, began taking music lessons as young teenagers from a local farmer in return for work.

Silas Whitman, chairman of the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee and son of Nezpercians band member Tony Whitman, told Johnson those who were at the schools had to make their own music in order to express their emotions. He added that some developed a love for popular music despite the boarding schools.

Once the Nezpercians formed, they traveled the most widely of any Nez Perce dance band during that era, even providing the musical accompaniment for silent films in a movie theater in Oklahoma, according to Johnson's article.

Taylor said in order to travel, band members often literally jumped onto trains with their instruments, anywhere from British Columbia to Arizona. McCormack's other daughter, Loretta Halfmoon of Lapwai, said they didn't mind.

"They loved to travel because (playing) is what they loved to do," Halfmoon said.

Johnson said that, from what she learned, some of the reasons they performed was to break up stereotypes.

"So often people used to think of Indians like in the past, and not as people just like us," Johnson said. "And so this is a way to say, 'We like to dance, we're doing the Foxtrot, we're just as contemporary and modern as you are.' "

But they also dressed in full regalia, with war bonnets and other traditional clothing.

"At the same time, you can say, 'Let's play into these white folks' idea of what Indianness is if it gives us the opportunity to play and make money,' " Johnson said.

Whitman told Johnson the Nezpercians faced discrimination in other forms as well. Band members and their families were not allowed to eat in the restaurant area or mingle with customers - they were expected to eat in the kitchen, perform and then leave.

Women also played a role in the band. Jane Spencer Williams, who would become White's wife, played the piano for them in their early performing days. White's nephew, Joyce, often joined them as a vocalist. McCormack's wife also occasionally sat at the edge of the stage in a buckskin dress, mostly for show.

The band traveled and performed up until about the 1940s, when Whitman said they started to drift apart.

But McCormack and others passed their love of music to their children, Taylor said. They danced to music at home, and she learned the trumpet while Halfmoon learned the saxophone.

"My dad told us, 'Music is important and we want you to play,' " Halfmoon said.

McCormack played the drums many years after the group stopped touring, until one fateful New Year's Eve. Taylor said they attended a dance at a restaurant and bar owned by minor league baseball player and longtime umpire Scrappy Curtis in Winchester. The Nezpercians played, and when the night was over, they did something unusual and decided to leave their instruments there just for the night.

Unfortunately, that was the night the tavern burned to the ground, along with McCormack's drums.

"After that, he didn't have drums to play anymore and he was sick," Taylor said. "It kind of affected his heart. ... After that, he started failing in health, having heart problems and everything."

Taylor and Halfmoon lamented the fact that music programs at the schools aren't what they used to be because they are the first programs cut when budgets are in trouble. They miss the days of marching bands and drill teams that would perform at events all over the area.

"It was pretty neat in our day, and it was exciting," Taylor said.

Taylor and Halfmoon said they haven't made it to Moscow for the jazz festival in recent years, but they went up there once when Fats Domino performed. They said they still have a deep love for jazz, a passion they got from their father.

Johnson said the most rewarding part of piecing together the history of tribal jazz musicians was seeing the love reflected in the band members' children, and learning about the passion they had for the music.

"These folks practiced really hard. They were serious about being as good a musicians as they could be," Johnson said. "That's why I called this 'Excellence in Indianness,' because these people set really high standards for themselves."

---

Moseley may be contacted at kmoseley@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2270.