It may seem unlikely — considering the precipitation of the past couple of weeks — but Idaho and Washington could be headed for an abnormally dry summer.

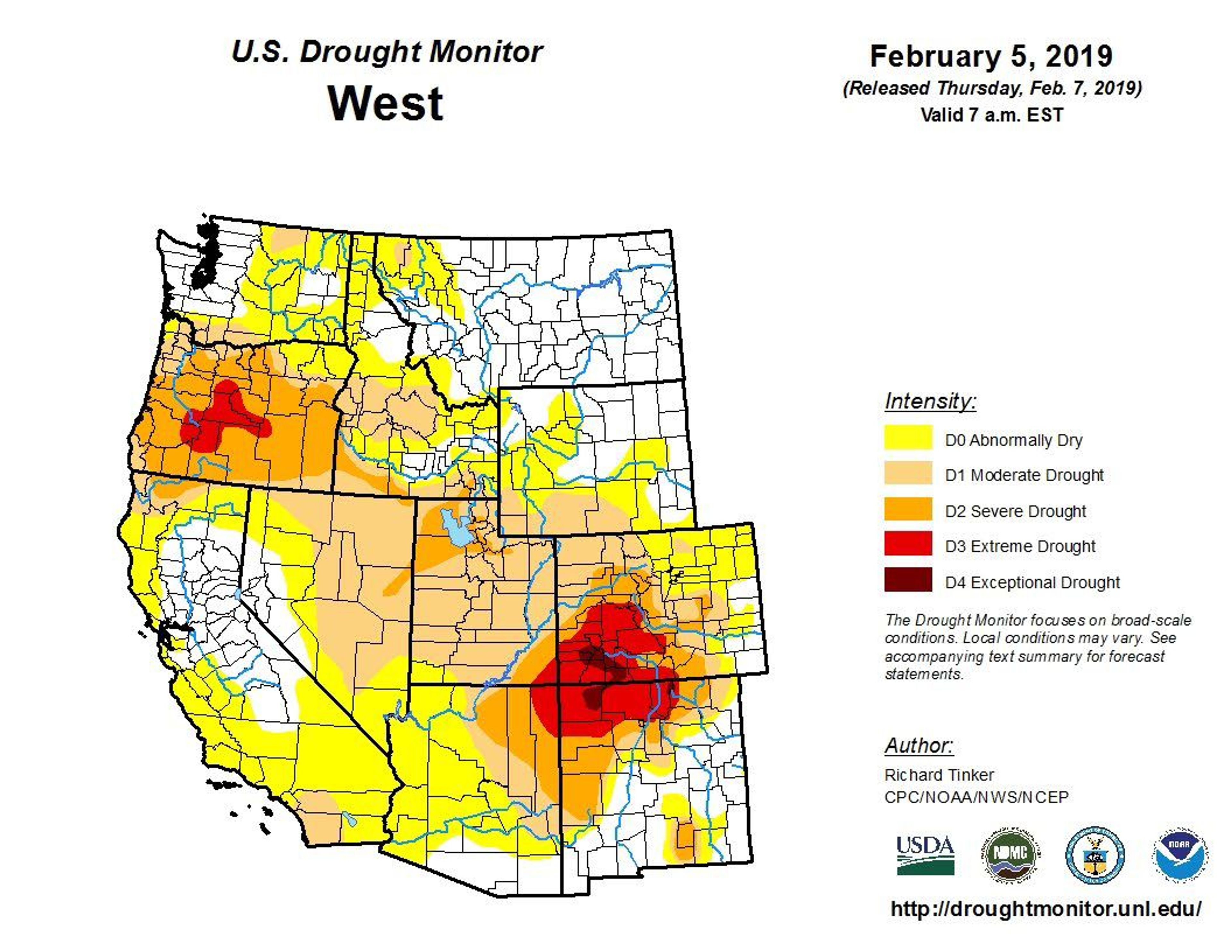

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently issued a climate prediction showing a worsening outlook for drought across the region. Both eastern Washington and Idaho, based on short- and long-term forecasts, may expect an abnormally dry spring and summer, according to the report.

“The seasonal outlooks forecast for the spring are showing warmer-than-normal conditions and drier-than-normal for the Northwest,” said Karin Bumbaco, who conducts research as the assistant state climatologist with the Office of the Washington State Climatologist.

“So I think that is a bit concerning, both with what snowpack we have, and we may not build up as much through the latter part of the snow season as what we’ve seen the last few years.”

While the situation seemed more dire in January, which was an unusually warm and dry month throughout the Pacific Northwest, Bumbaco said the precipitation of the early part of February helped replenish snowpacks, particularly in the Cascade Mountain region and the panhandle of Idaho.

“I’ve been pleased with how the snowpack has improved over the last month,” she said. The Cascade region has built up to about 85 percent of normal, while Idaho’s snow level is between 90 percent to 95 percent of normal.

Climatologists “are nowhere as concerned as it looked (in December), and it looks like we’ll have another cool week or two in the Northwest. But there is some concern still.”

Bumbaco said long-term trends throughout the Northwest show temperatures have been warming in all seasons of the year.

“I think that’s becoming clear,” she said. “Washington state had the warmest year on record in 2015, and that’s going back to 1895. In terms of snow, there hasn’t been as much of a drop-off in snow over the last 30 years, but longer-term trends show it has decreased overall. I do expect there to be more decrease in our snowpack in Washington and Idaho in the future than what we’ve already seen, due to climate change.”

Defining ‘drought’

Drought is defined by the National Weather Service as a deficiency in precipitation over an extended period. It is a normal, recurrent pattern that occurs in all climate zones, and the duration of droughts varies widely.

Sometimes droughts develop quickly and last only a short time. There are other cases, when coupled with extreme heat and wind, that droughts can span multiple years or even decades.

The National Integrated Drought Information System was established by Congress in 2006 to implement a monitoring system at federal, state and local levels. The system includes monitoring, forecasting, response, research and education and it features outlooks and monthly field reports from various agencies across the country.

Drought has a major impact on agriculture, resulting in soil water deficits and reduced groundwater and reservoir levels needed for irrigation.

According to federal data, there have been three or four major droughts in the past 100 years. In the 1930s Dust Bowl and the 1950s, droughts lasted five to seven years and covered large areas of the continental U.S. Agricultural losses during these events have cost the country hundreds of billions of dollars.

Since 2000, the longest duration of drought in Idaho lasted 258 weeks, beginning on Jan. 30, 2001, and ending on Jan. 3, 2006. The most intense period occurred in 2003 when the drought affected 40.78 percent of Idaho land.

In Washington, the longest duration of drought since 2000 lasted 116 weeks, beginning Jan. 7, 2014, and ending March 22, 2016. The most severe period occurred in August 2015 when 84.6 percent of Washington land was affected, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Too early to panic

In spite of the warnings, it’s too early yet for farmers to panic, said Steve Van Vleet, a regional Extension specialist with Washington State University at Whitman County.

“It’s been very, very dry, but our springs have been relatively wet, and that’s when we get a lot of moisture,” Van Vleet said. “It was drier than normal, but when it comes to crop production, we had the highest yields ever this last year.”

The lack of rainfall in September and October caused some farmers to delay planting their winter wheat crops, which means plants may not have been fully emerged when the winter weather hit.

“The snow we’re getting now is good, but if the snow is not available earlier and if we have extremely cold temperatures below zero, then that’s when we really have problems,” he said. “We really haven’t had that, so our crops should be quite good this year, too. Especially if we get spring rains like we’re used to.”

Farmers count on getting their spring crops planted during a window of time between March and May, then keep their fingers crossed for a good sprinkling the latter part of June.

That moisture rejuvenates winter crops that have lain dormant over the winter and gives the spring seedlings a boost to keep growing over the summer, when there may be no further rain.

“If we don’t have rain starting in April and May … that’s when we could really get worried,” Van Vleet said. “There could be a serious problem for our spring crops, and it will reduce yields of winter grain crops also. That’s the time frame that growers are going to be most concerned about.”

Lack of moisture also makes plants susceptible to disease and pests, he said. Many insects thrive in hot temperatures, and stripe rust, a fungus that affects grain crops, is likely to be a big problem.

“If you don’t have a hard winter to kill those (threats),” he said, “then we can have a problem with all crops.”

Hedberg may be contacted at kathyhedberg@gmail.com or (208) 983-2326.