POCONO MOUNTAINS, Pa. — A dense, gray cloud settled above Monroe County in the first days of February, blocking the sun’s attempts to break through. More than a month since the U.S. shifted its gaze to this rural region, a shame has fallen over its residents, the result of an incomprehensible crime on the other side of the country.

Situated below the forested hillsides in Brodheadsville lies the Pleasant Valley School District’s two-story brick campus, where Bryan Kohberger went to school and later worked. Two weeks after Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a quote from the holiday’s inspiration still featured on the district’s public message board: “Darkness cannot drive (out) darkness; only light can do that.”

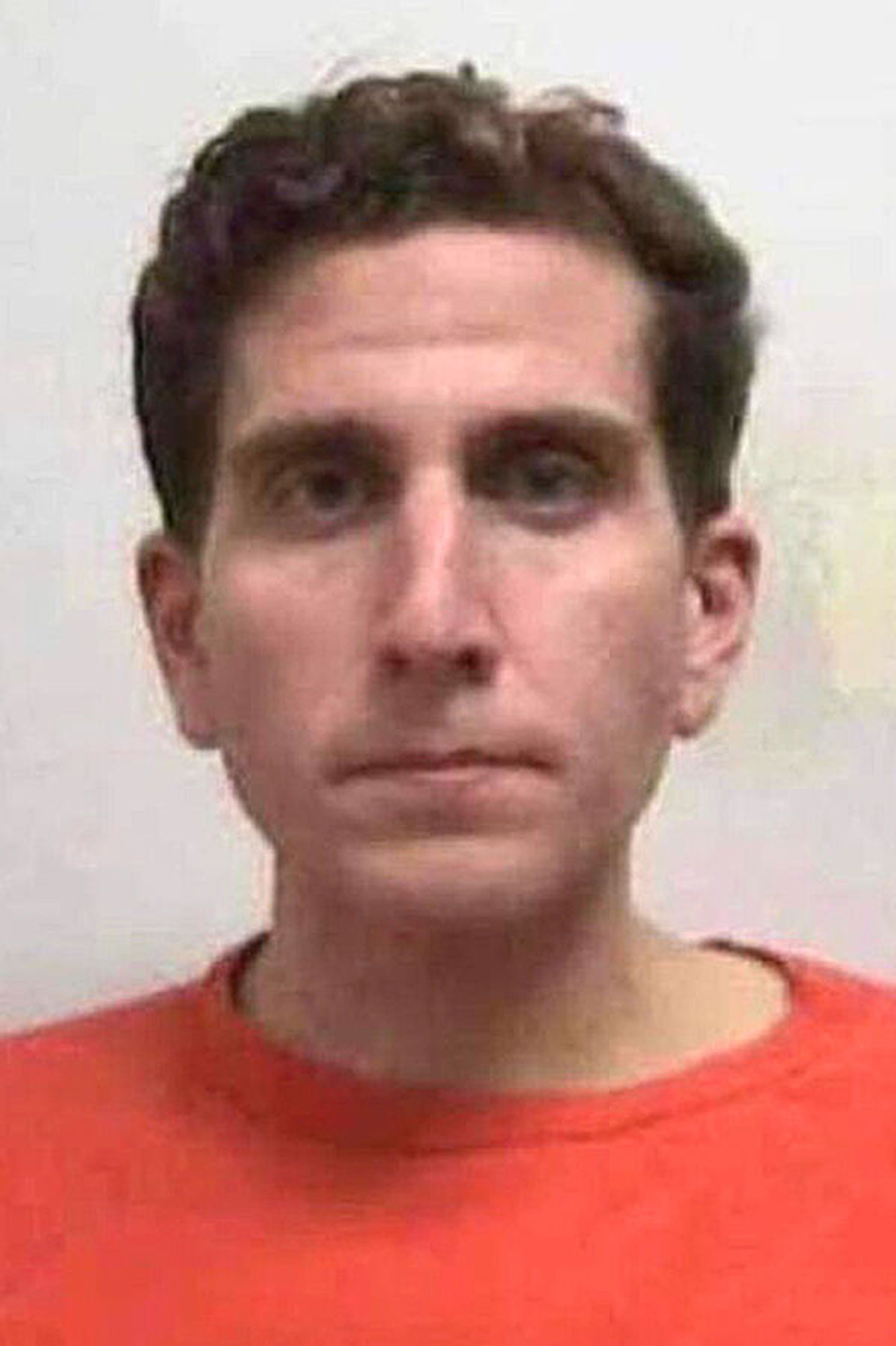

In December, Kohberger was taken into custody in the cover of night. Instantly, a quaint community used to the calm of its remote geography became a new epicenter in the widening investigation into November’s University of Idaho homicides. The 28-year-old alleged killer hails from the area’s bundle of townships and was staying with his parents when law enforcement burst in and ended a seven-week manhunt.

One tormented community grew to three as news surfaced that Kohberger, a Washington State University graduate student, was arrested in eastern Pennsylvania some 2,500 miles from the crime scene. Four college campuses were entangled in the tragedy. But unlike the sister cities of Moscow, Idaho, and Pullman, Washington, grieving together, Kohberger’s hometown was made to ache in isolation.

“For the community here, it’s devastating,” said John Gress, the principal of Pleasant Valley High School when Kohberger graduated in 2013. “Out of all the schools, out of all the areas, why? It’s disappointing, and I don’t know if we’ll ever find out why.”

Neighbors of the red-roofed, four-bedroom home on an acre in nearby Effort, Pa., where Kohberger was raised, were just as astounded. For years, their children took the same route to school from the same corner bus stop as he. They remembered the quiet, heavyset boy who was picked on over his weight. He sat up front and mostly kept to himself.

Today, Kohberger is charged with first-degree murder in the stabbing deaths of four college students: UI seniors Madison Mogen and Kaylee Goncalves, each 21, junior Xana Kernodle, 20, and freshman Ethan Chapin, 20.

And Kohberger’s old neighborhood is left to try to make sense of a senseless act.

“No bells ever went off,” said Barbara Tokar, 58, a nearby homeowner and mother of one of Kohberger’s classmates, adding that her daughter told her she never noticed any possible warning signs. “It makes me sick in my stomach. You never know. You just never know.”

Natori Green, 27, grew up four homes from the house where Kohberger lived, and they both graduated from the high school in 2013. She recognized the unusual nature of such national attention on the small community, where the school district remains one of the county’s largest employers.

“You see it on the news. It’s surreal,” Green told the Idaho Statesman from her driveway.

Since moving back home with her family after college, Green said, she’s heard about the passing of several Pleasant Valley classmates, rattling off the list of causes: drugs, car accident, drugs, military, drugs again.

Drug abuse is a problem in the area. The region has one of the highest rates of overdose deaths in one of the worst-hit states for the U.S. opioid epidemic. Kohberger had his own lengthy battle with drug addiction, several former friends told the Statesman.

Although a number of deaths and incidents concerned past schoolmates, Kohberger’s situation is entirely different, Green said.

“It’s actually very sad, and there’s a lot to take into mind and factor,” she said. “We don’t know why, and it’s sad to hear on both sides.”

‘Desire to be the alpha’

For Kohberger’s former circle of friends during high school, the allegations were immediately jarring and difficult to comprehend — even for those familiar with his unpleasant side.

“It’s hard to put into words,” Thomas Arntz, 27, told the Statesman in a phone interview. “I just, it was the initial shock of hearing what he had been accused of. My first thought was, ‘Where is he now? Are my parents safe?’ Because you couldn’t process it all at once.”

Arntz remembered Kohberger as similar to himself when they met in their early teens: awkward and fairly reserved. During hangouts after school and on the weekends, they bonded over video games and wandering the wooded neighborhood. Arntz said he came to appreciate Kohberger’s sense of humor, wit and ability to observe.

But Arntz said he hadn’t spoken to Kohberger in about eight years, having chosen to cut ties because he said his friend’s personality grew grating over time. Kohberger would frequently play mind games with him, Arntz said, including once when he was upset after the death of his aunt. He made clear to Kohberger that he wasn’t in the mood, but his friend refused to relent with what Arntz called psychological mistreatment that became more commonplace.

“He always wanted to be dominant physically and intellectually,” said Arntz, who was a year behind Kohberger in school. “He had to show that he was smarter and bigger than you, and try to put me down and make me feel insecure about myself. So much of that was a torment and I didn’t want to be around him anymore.”

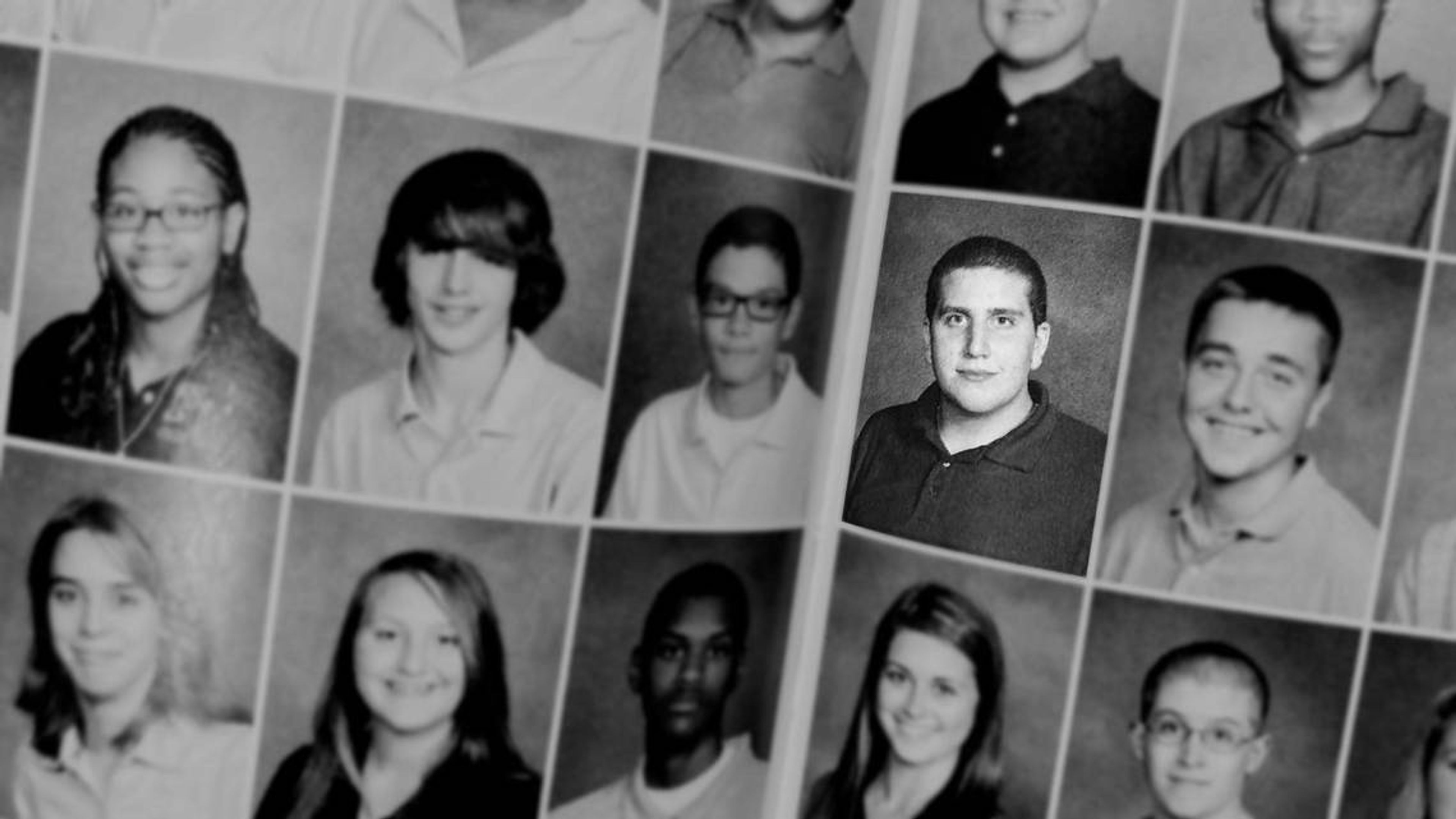

By high school, Kohberger told friends of his interest in law enforcement. His sophomore year high school yearbook features Kohberger dressed in a uniform and in the midst of a push-up during his law enforcement class at the county’s half-day technical school. Kohberger hoped to become an Army Ranger, the caption read, but his interest was primarily law enforcement, Arntz said.

The program helped students eventually become police officers, firefighters or EMT, said Donna Yozwiak, Kohberger’s guidance counselor through most of high school. His parents, who also worked for the school district, were active in attending meetings to help steer their son, she said.

“I recall no problems. He was a regular kid, and thankfully his parents were involved in his education,” Yozwiak told the Statesman in a phone interview, adding that she remembered Kohberger as a good student. “I don’t recall anything that was out of the ordinary.”

Gress, the high school’s principal until retiring in 2017, told the Statesman he was an administrator who made efforts to get to know students in his two decades in the position and 41 years in the school district. He only vaguely recalled Kohberger, he said, in part because Kohberger was enrolled half the day at the off-campus technical school and wasn’t involved in any after-school activities offered by the district.

What many people do remember of Kohberger from his high school years was his considerable weight loss. The dramatic change occurred between his junior and senior years, Arntz and two other former friends said.

Kohberger started kick boxing every day after school and running in the evenings with a neighbor, Arntz said. He also became hyper-focused on what he ate, his friends recalled — to the point that he developed an eating disorder that required hospitalization, Jack Baylis, 28, another of Kohberger’s inner circle at the time, told the Statesman.

Arntz estimated that Kohberger weighed more than 300 pounds and the amount he lost was as much as half his body mass. And it was so rapid that Kohberger had tummy tuck surgery because he was left with so much excess skin, Arntz and Baylis said. Kohberger’s high school yearbook photos from his sophomore through senior years, reviewed by the Statesman, showed his physical transformation.

During this same period, Arntz said, Kohberger’s personality also shifted and he became more aggressive. Arntz provided similar details in an interview with the FBI, he said.

“It almost seemed to me he had a desire to be the alpha,” Arntz said. “For no reason, he’d try to grapple me and put me in headlocks when I didn’t want to. He tried to portray it as just boys being boys, but that’s not the way I ever took it.”

Years later, after Arntz enlisted in the U.S. Army and was deployed overseas, Kohberger sent him a Facebook message offering his congratulations, he said, and apologizing for how he treated him when they were younger. Arntz said he didn’t respond.

Suspect’s, region’s drug dependency

Monroe County rests at Pennsylvania’s northeastern edge bordering New Jersey and is just one county over from the New York state line. Consequently, the Poconos region sits adjacent to the nation’s largest heroin trafficking hub and market, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

Pennsylvania maintains one of the nation’s highest rates of drug overdose deaths annually, consistently in the top five in recent years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. In 2020, Monroe County far outpaced the state in the category, ranking third among Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, according to the latest data available from its Department of Health.

By comparison, Idaho and Washington state routinely rank in the bottom 20 nationally for deaths from drug overdoses.

Between the 1990s and 2010, Monroe County’s population nearly doubled to 170,000 as more people from Pennsylvania’s neighboring states flooded in during Kohberger’s upbringing. The close of his high school career and the years that followed, Kohberger’s friends said, were marked by a marijuana habit graduating into a heroin addiction.

Kohberger attended the county’s technical program his sophomore and junior years of high school. But he switched for his junior year from law enforcement to focus on heating, ventilation and air conditioning, like his father, who worked in maintenance at the school district for a time. For reasons that are unclear, Kohberger then transitioned out of the technical school his senior year to earn his diploma through the high school’s online program, Yozwiak said.

Neither Kohberger’s HVAC instructor, who today works as a technical school administrator, nor his law enforcement instructor returned interview requests from the Statesman.

Tanya Carmella-Beers was at that time a technical school administrator who oversaw student discipline and mental health. She remembered Kohberger, she told the Statesman, and acknowledged that her interactions with him would have fallen within that scope.

Carmella-Beers declined to answer questions about Kohberger, citing protection of such information under the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. But she spoke generally about the circumstances that could force a student to change their focus within the program.

“Sometimes, depending on the disciplinary offense and any issues surrounding it, it may not be the student’s choice to be removed from a program — particularly a program that might have many rules and regulations in place,” Carmella-Beers said by email, noting the law enforcement program barred certain behaviors. “In general, a student can be very strong academically and perform very well in clinical work, but one or more infractions would take the opportunity to participate in that program away.”

Casey Arntz, 29, who graduated high school two years ahead of Kohberger, also was among his circle of friends, along with her younger brother, Thomas. As an upperclassman, Kohberger started spending time with another group of high school kids with whom she and her friends didn’t gel, Casey Arntz recalled.

“Honestly, I feel he was looking for validation, and that’s why he fell into that crowd,” she told the Statesman in a phone interview. “And honestly, it’s why he fell into the whole drug scene.”

Jeremy Saba, a neighbor two houses from Kohberger’s childhood home, was part of that group and introduced Kohberger to heroin, Baylis, Casey and Thomas Arntz said. Saba and Kohberger can be seen together in a photo that Saba posted on Facebook in August 2016 — four months after Saba was arrested and charged with a DUI and misdemeanor possession of drug paraphernalia. He later pleaded guilty to both charges, according to Pennsylvania court records.

“I didn’t like him personally because he got my boy into heroin,” Baylis said by phone, mentioning his falling out with Kohberger for several years over his drug issues. “I think drugs goofed him pretty bad. He was having a time. He’d tell me, ‘I’m clean now, I’m totally clean now,’ and he’d have bleeding track marks” on his arms.

Kohberger had no known criminal record before he was charged with four counts of murder and one count of felony burglary in the Nov. 13 Moscow homicides.

Saba was arrested again in September 2018 for misdemeanor possession of a controlled substance, pleaded guilty and received a year probation. In March 2021, Saba, 27, died of an accidental drug overdose, according to the Monroe County coroner.

In high school, Kohberger also started using heroin with classmate Ashley Flugel, Thomas Arntz said. Flugel later faced a raft of drug charges in 2017 and 2018, including a felony count of intent to distribute a controlled substance. In May 2018, before her court appearance, Flugel, 23, died of an accidental drug overdose, according to the county coroner’s office.

Between Kohberger’s frequent invites to smoke marijuana, he told Casey Arntz in March 2013 that he finished his online school requirements early, according to screenshots of Facebook messages that Arntz provided to the Statesman. He was looking forward to college that August, Kohberger wrote.

About two months later, Kohberger reached out to her again to ask for a ride after he said his car broke down, and she agreed to help him, the messages showed. Weeks later, Casey Arntz came to learn that Kohberger’s errand was actually to buy heroin and needles, she said.

“He literally used me to get it,” she told the Statesman. “I was freaking out and not happy I had heroin in my car and didn’t even know.”

The correspondence shows Casey Arntz sent Kohberger a message that May scolding him for putting her in jeopardy had Kohberger been caught. He responded with three words.

“I’m in rehab,” Kohberger wrote. He offered an apology more than three weeks later, which she rebuffed.

Shortly after high school in January 2014, Kohberger again reached out to Casey Arntz to ask how college was going, the Facebook messages showed. She responded that she was stressed out over school projects.

“Be proud, you’re making something of yourself. I’m NOT haha,” he wrote, saying he withdrew from college because he had to go to rehab. “Life after was dull.”

‘It’s almost unbelievable’

During the workweek, regulars slide in to occupy one of 10 seats at the bar at Lynn’s Motel on State Route 115 in Effort almost as soon as the doors unlatch at 4 p.m.

One of the first in on a Wednesday is a school bus aide just off work. She grumbled about losing a lunchtime bout with a stubborn piece of rye bread that knocked out two of her fillings — one on each side of her mouth. She’s ready for her usual Seagram’s 7 and Sprite, and make it a double.

Adorned with timeworn red carpeting and wood-paneled walls, the local watering hole is one of few left in the area, and patrons are all on a first-name basis. A metal sign behind the bar declared the establishment a fallout shelter, with a folded piece of paper beneath it carrying a scrawled message that draws recurring laughs from customers: Do Your Drugs Elsewhere.

The bar doesn’t see a lot of new faces. When it gets one, especially if they’re visiting from Idaho, it garners the interest of the staff and the everyday clientele. They were all following the quadruple homicide case, too, before it improbably landed on their doorstep with Kohberger’s arrest late last year at his parents’ house, just up the road along the oak-lined byways.

“I was watching the news and saw that they caught him,” bartender Amy Miltner explained. “And it’s in Albrightsville! What? That’s a mile from my home.”

Overhearing word of an out-of-towner from Idaho, an Army veteran seated at the corner of the bar with a pencil-thin mustache and a firm grip on a bottle of Coors Light chimes in.

“Not from Moscow, I hope,” he said. “Well, welcome to the Poconos.”

Next door to Lynn’s is a roadside pizzeria, formerly called New York Pizza Girl. Kohberger worked there in 2013 and 2014, Rich Pasqua, a Pleasant Valley High School graduate a few years older than the suspect, told Fox News and The New York Times last month. Pasqua did not return Statesman requests for an interview.

Pasqua, 31, who today works at a drug rehab clinic in the area, said he and Kohberger would use heroin together.

“He didn’t have many friends, so he would do anything to fit in,” Pasqua told Fox News. “He was a big heroin addict, and so was I. … I work in treatment and everything, but back then I was using, and so that’s how I know for a fact he was using. I got high with him a couple times.”

Charles Conklin, 61, owns the building the pizzeria occupied, as well as the neighboring fish hatchery that includes a stocked lake where people pay to fish for a variety of trout and bass. In the summer of 2011, Kohberger briefly worked there a few months as well, cleaning people’s catch, Conklin recalled and Kohberger wrote on a school district job application obtained by the Statesman.

He wasn’t there long, however, Conklin told the Statesman, because Kohberger didn’t show himself to be very personable with customers and also wasn’t improving at filleting the fish. He let him go.

“You’ve got to do a good job on your cuts, you have to be friendly to people, at least try to make some eye contact,” Conklin said. “It just wasn’t his thing.”

Within an hour of Kohberger’s arrest in December, Conklin said, he got a call from a former longtime employee who reminded him of the high school kid they fired more than a decade ago. The revelation floored him.

“There aren’t words to describe how disturbing it was,” Conklin said. “We’re a small area, small community, so for things like that to happen, shocking — totally shocking. I know this is shocking for anyone, and for him to be from this area and actually worked here, it’s almost unbelievable.”

Post-recovery road reaches shocking turn

Several years after they last spoke, Baylis said, he and Kohberger reconnected. Baylis said the two would exchange Facebook messages and Kohberger would call him to talk every week or so. Kohberger told him he no longer used drugs when the subject came up.

“At some point, he said, ‘Don’t ever bring it up again. We’re past that,’ ” Baylis told the Statesman.

In May 2018, Kohberger told Baylis in messages on Facebook that he hadn’t used drugs in two years, according to screenshots Baylis shared with The New York Times.

“I only used when I was in a deep suicidal state,” The Times reported Kohberger wrote to Baylis. “I have since really learned a lot. Not a person alive could convince me to use it.”

Casey Arntz said she ran into Kohberger a year before that at a mutual friend’s wedding, which was the last time she saw him. He appeared to have pulled his life together, she said, and shared that he was in college and working as a security officer for the Pleasant Valley School District.

“It was so good to see someone come back from that dark place,” Casey Arntz told the Statesman, saying she gave Kohberger a big hug when she greeted him. “He was kind of very standoffish, and not very sociable. I believe he left early as well.”

Kohberger started with the school district in 2016 as a fill-in custodian and courier before moving into security part-time, according to documents the Statesman obtained through a public records request. He was later credited in December 2018 with helping save the life of an employee at the high school after a medical emergency, The Pocono Record reported.

In response to the records request, the school district cited Pennsylvania’s exemptions in withholding several documents from public disclosure. Among them were those related to non-criminal complaints, written criticisms of an employee or discipline records in a personnel file. Kohberger resigned from his position in June 2021, records released by the district showed.

The Pleasant Valley School District did not respond to Statesman requests for comment beyond the public records request.

Kohberger attended Northampton Community College in eastern Pennsylvania and graduated in 2018 with a major in psychology, according to a school spokesperson. The school is unwilling to say anything else about Kohberger, directing all other questions to law enforcement.

Kohberger went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in 2020 and his master’s in 2022 from DeSales University, according to a statement the university released the day he was arrested. The university is about an hour south of the home where Kohberger’s parents moved and he continued to live while in college, public records indicated.

DeSales faculty are not accepting interview requests about Kohberger, a university spokesperson told the Statesman by email. The university will cooperate with law enforcement’s investigation however it can, she said, but declined to offer specifics.

Kohberger majored in psychology for his bachelor’s, Boyce Jubilan, chair of DeSales’ psychology department, told The Philadelphia Inquirer the day of his arrest. He received his master’s through the university’s online criminal justice program, Michelle Bolger, professor in DeSales’ criminal justice department, told The Daily Mail last month.

Katherine Ramsland, a famed forensic psychologist who teaches in DeSales’ criminal justice master’s program — and collaborated on a book with notorious serial murderer Dennis Rader, better known as the BTK Killer — confirmed to LehighValleyNews.com that Kohberger took at least one course with her. In an email, she declined a Statesman request for an interview.

Last summer, before Kohberger started in Washington State’s criminal justice and criminology Ph.D. program in August, he posted a research questionnaire to Reddit seeking volunteers to discuss their decision-making and behavior in the midst of committing a crime. Bolger told The Daily Mail she helped Kohberger with the project, which was part of his master’s thesis at DeSales.

‘A customer we had to address’

Jordan Serulneck, 34, owner of Seven Sirens Brewing Co. in Bethlehem, Pa., just north of DeSales, thinks Kohberger was through his taproom a handful of times from 2020 to 2022. Serulneck told NBC News in December that he approached the man he believes was Kohberger to ensure he behaved while at the brewery after female patrons and staff said he previously made them feel uncomfortable and made rude comments.

“It looked like him, his name was Bryan and it was in that time frame,” Serulneck recounted to the Statesman this month while seated at the bar. “He seemed dumbfounded, finished his beer and I never saw him again.”

Since then, Serulneck said, he’s been hounded by members of the media and people who said he was just chasing publicity related to Kohberger and the Idaho homicide case. He rejected the notion, saying he’s turned down interviews with Dr. Phil and documentary projects underway about Kohberger.

“I don’t want anything about this,” Serulneck said. “He was just a customer we had to address. It was anticlimactic. I thought it would’ve blown over by now, but I still get calls.”

Kohberger showed similar behaviors while attending WSU’s Ph.D. program, fellow graduate school classmates told the Statesman last month. During the fall semester, he was said to be increasingly condescending toward women in class discussions.

In December, Kohberger was fired from a teaching assistant position for failing to meet the “norms of professional behavior,” according to The New York Times. He had repeat altercations with the criminal justice professor under whom he worked, did not improve upon his conduct and performance, and also exhibited concerning behavior around female students, including allegations he followed one to her car, the Times reported.

WSU faculty at their end-of-year meeting chose to pull Kohberger from the role, eliminating his funding for the Ph.D. program, according to the Times. The university sent him a termination letter on Dec. 19 — three days after the end of finals for the fall semester, Kohberger’s first term at WSU.

By then, Kohberger was back home. He had left Pullman for winter break, driving across the country with his father in a 2015 white Hyundai Elantra and arriving at the family’s house in Pennsylvania on Dec. 16, according to a probable cause affidavit. Kohberger was arrested at the home on Dec. 30 and on Jan. 4 was flown to Idaho, where he awaits his next scheduled court appearance in June.

Seven weeks after law enforcement extracted him from this outlying area of the Northeast, community members said they remain baffled.

Donna Yozwiak, Kohberger’s high school guidance counselor, said she immediately remembered Kohberger as word of the incident spread across Monroe County, where she still lives. Like many, she said she was shocked.

Despite the nation’s ongoing attention on the case, including its intense focus on the Poconos, Yozwiak said she wants to see the judicial process play out properly. Perhaps then, she said, those impacted can begin to heal on both sides of the country.

“I’m watching the news as well as thousands of other people,” she said. “I’m just hoping that this all works out and just that the truth comes out. That’s all we can hope for.”