Boise teacher plays guitar for tips to get by

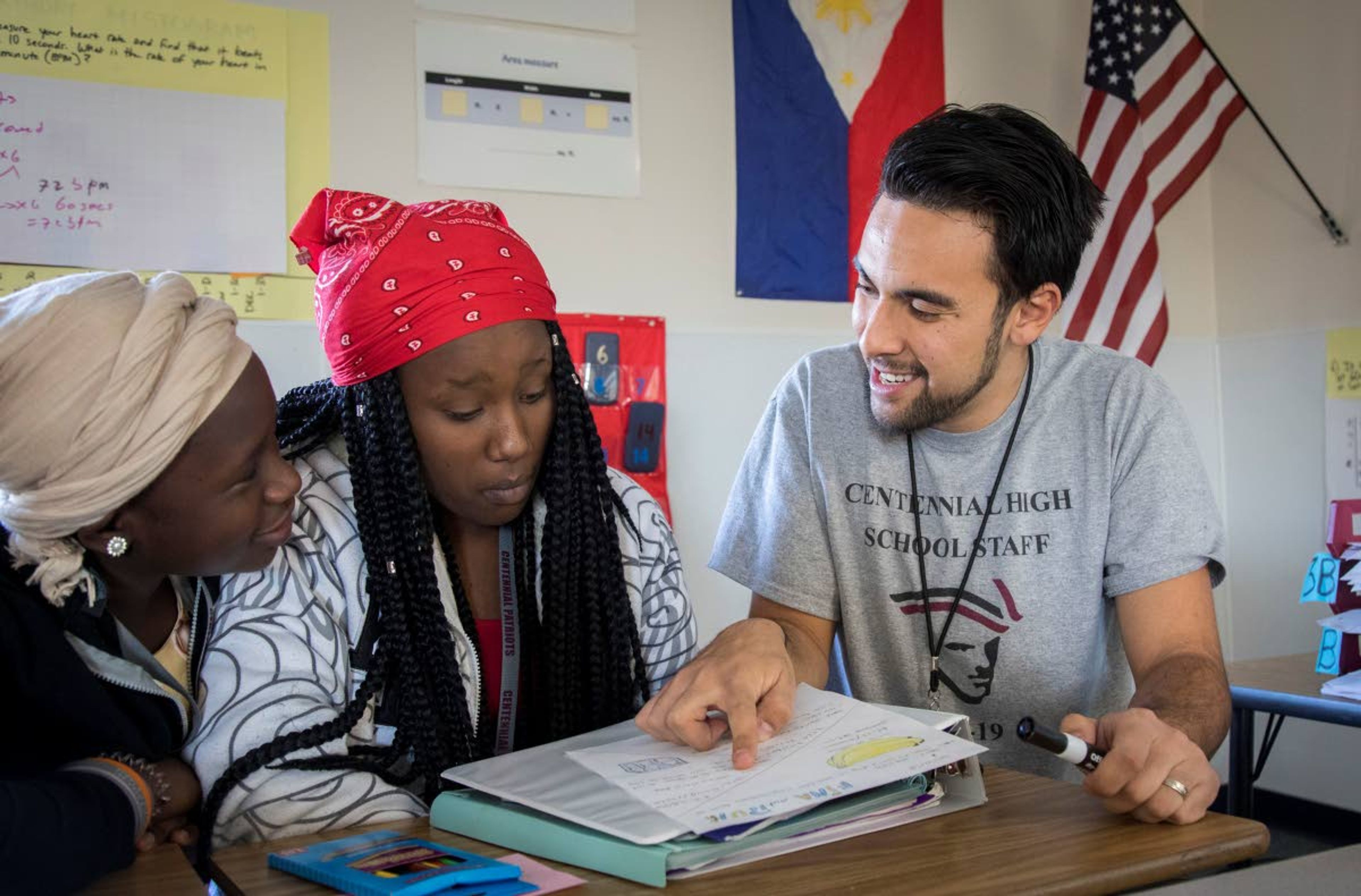

Tanner Faris is a math instructor at Centennial High School, working with refugee kids

BOISE — Guitar case slung over his shoulder, Tanner Faris coasts up the sidewalk on his bike. Eying his spot in the busy Saturday market, he sets up a music stand and, with practiced ease, tapes his corrugated cardboard signs against the wind.

Because it’s the signs that stop people.

“My wife said to me: You’re not going to make any money if you’re just another guy with a guitar,” Faris told the Idaho Statesman .

The neatly hand-lettered posters say: “Not homeless. Just a high school teacher.” The signs are the hook; he hopes the music will keep people lingering — and his guitar case is open right beside, an invitation for spare change and dollar bills.

Faris, 25, is a math teacher in Centennial High School’s English as a New Language department. He helps refugee kids, ages 14 to 20 years old, learn math — and English — through immersion in reading, writing, speaking and listening.

He and his wife are actually in better shape financially than they have ever been. But Faris is a brand new teacher, and his salary is at the bottom of the pay grade. He isn’t cynical about his salary, because he loves what he does, but playing for tips certainly helps the budget.

“(Busking) has become an awesome source of extra income for me. But my heart really is with the kids. I wouldn’t be (busking) if it wasn’t for them,” he says.

———

Just married and freshly graduated from the University of Oregon, Faris and his wife, MJ, a Boise State University student, settled in Boise in 2017 to start their life together.

Faris got a job as a paraprofessional in the English as a New Language program at Lewis and Clark Middle School, and filled out his workday in a pizza shop, bringing home about $600 a month from each job, working from morning till night.

“We were feeling the crunch,” he said. “That’s when we really were watching every penny.” When they budgeted frugally, they even had money to put into savings and tithe 10 percent to their church.

“We were finding a way to make that work,” he says.

But part of “making that work” meant a summer job — and Faris wasn’t excited about working in the pizza shop (in part because he also wanted to do some long-long-distance bike rides, like from his doorstep to Banff National Park in Canada).

“I thought, well, shoot, I can play the guitar,” he says. “I wasn’t sure how successful I was going to be just because it’s a dime-a-dozen guys strumming guitars on the sidewalk.”

He decided to give it a shot.

The first time out, he picked what turned out to be a fairly obscure place and made just $30 or $40 dollars. “But I thought, ‘Wow. I could have sat at home and played guitar for two hours and made no money.’ That’s when I was like: This is a thing. I have to go again.”

He made his sign to stand out, and it was instantly successful.

“I was really impressed by how generous everyone was and how many grateful people I met who would say, ‘Hey, thanks for being a teacher,’ ” he says. “Or fellow teachers who would say, ‘We know exactly how it is.’ ”

He goes out weekends and First Thursdays, and special occasions like the Spirit of Boise’s hot air balloon event Nite Glow.

“It’s just been so good to me, and it really did turn a legitimate summer job,” he says. In fact, in August, he made more on the street than he did teaching as a paraprofessional.

But teaching is his calling. Faris became a full-time teacher last January.

That qualified him and his wife for health insurance, so the state’s health insurance exchange dropped MJ’s coverage. However, her health insurance through the school district cost $600 a month — far, far more than the exchange.

They’ve solved that insurance wrinkle, but for a while, Faris’ busking paid for his wife’s health insurance.

“That made the side hustle even more necessary,” he says.

And they’re just starting their life together: They want a family; they want to buy a house. They’re contributing toward a retirement fund; they’ll need to pay MJ’s tuition and school loans. And they want to support their church.

“We joke all the time that we’re poor, but it’s all relative,” he says. “We’re making under $40,000 a year between the two of us, but look at it — we’re doing fine. Couldn’t be happier right now. (We’re) just preparing for what comes next.”

He jokes that his mother stills jabs him every now and again. “She’s like, yeah, you should have been a doctor.” But Faris laughs. “I’m like, oh, you know, I didn’t really enjoy chemistry.”

He laughs again. “I am where I love to be. And we’ll see where it goes.”

A LOVE OF LANGUAGES AND CULTURE

Faris went on a two-year mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 2014, which was pivotal in his life. He served in McAllen, Texas, became fluent in Spanish and developed a real love for languages.

“The people down there, I consider them family,” he says. “They took us in just like we were. After seeing that and how comfortable I felt, I realized how important language was to establishing that connection to a culture.”

When he began working in the West Ada School District, that feeling was cemented. He prefers the idea of a “mixed salad” to that of a “melting pot,” and encourages the parents of his students to preserve their culture along with their language.

“That’s why I want to learn Swahili. I want to pick up Arabic eventually,” he says.

“I feel like it’s a way I can meet (my students) halfway. I’m asking them to do something really hard, and I’m trying to do the same and show that I’m in it as much as I’d like them to be.”

He wants to be more than a teacher; he wants to be their advocate.

“I want to speak for them and with them,” he says.

English as a new language

Centennial High School is a magnet school for students learning English. The program is unique in that students learn English as well as subject matter — like math, social studies, speech — at the same time. It’s called “sheltered English instruction.”

Faris says the lesson plans between all the program teachers are carefully structured to include reading, writing, speaking and listening. Students are tested several times a year on a scale of one to five, and at a “2,” students can join general education classes.

Some students come into the program with little to no math, history or any educational background. Other kids come speaking four or five languages already, which is why the program is no longer called “English as a second language.”

“They’re super-talented kids,” Faris says. “We want to get them (speaking) English, and we want to create a really safe environment for that to happen.”

He’s excited about new ways of teaching that encourage students to interact with teachers — and with each other — to practice their language skills. Instead of, for instance, the lectures he received as a student.

“We, as the rising generation, are going to change the way that education is typically thought of.”