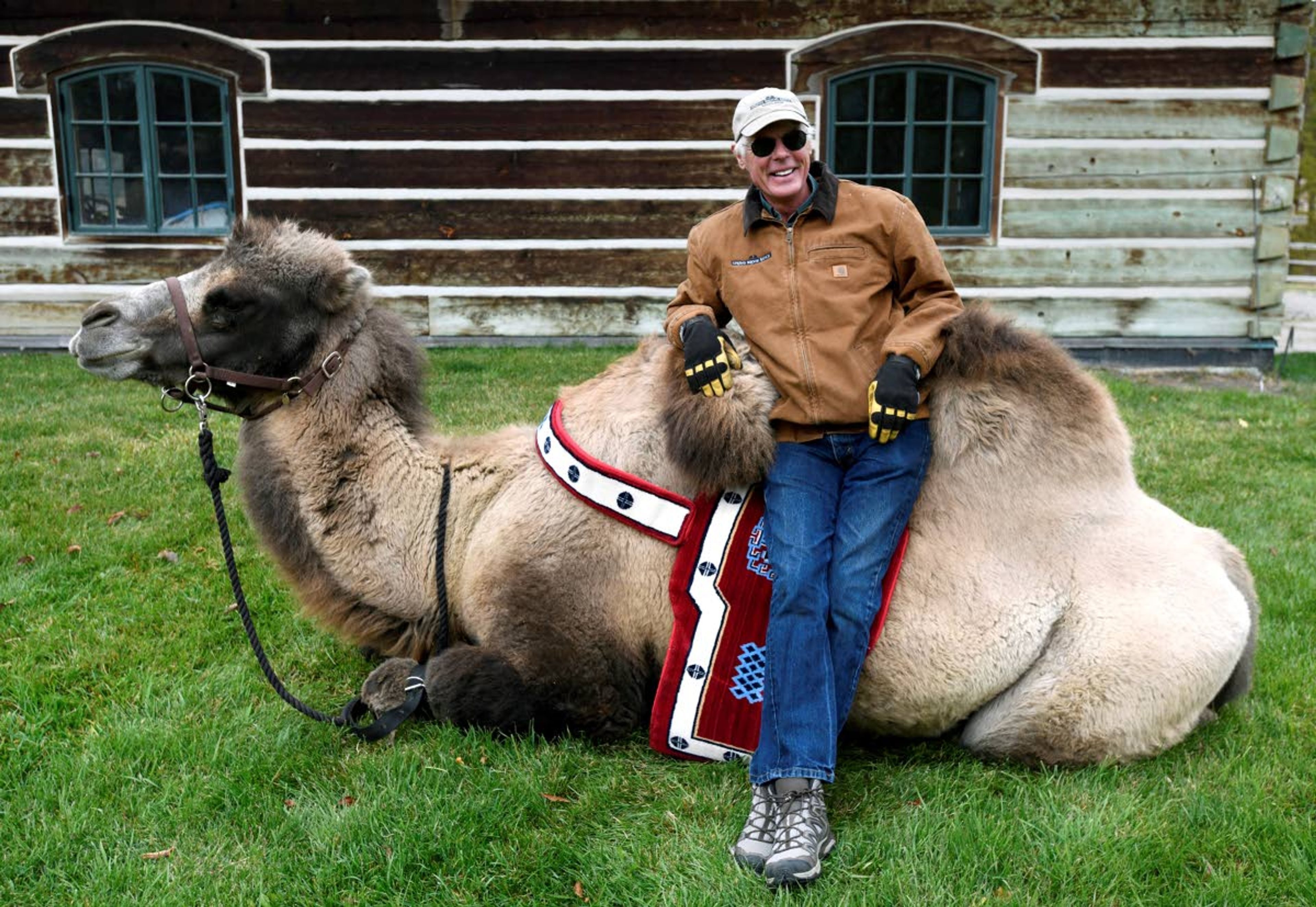

Adding a camel to the mix

Jim Watson gets Carlos the camel for his yak ranch in Montana

KALISPELL, Mont. — Carlos lets out a long, low-pitched protest moan — sounding suspiciously like Chewbacca in the Star Wars movies — as Jim Watson says “sook sook” and gently pulls the enormous camel’s head and halter downward.

Carlos’ front legs collapse onto his calloused knees, followed by his accordion-like hind legs, with his salad-plate-sized, double-toed feet folded underneath him until he’s comfortably kneeling. Watson scratches Carlos’ mullet-styled mane behind his ears, whispers sweet nothings into the one-ton ungulate’s ear, then turns to his visitors.

“I really like him,” Watson said with a southern drawl, while sporting an ear-to-ear grin.

Theirs is a language of love that’s not always spoken in English, but translates well.

“He’s very dramatic and emotional, and he vocalizes a lot,” Watson told the Missoulian. “It can sound like you’re killing him, but if you’re petting him and he really likes it, he kind of purrs and talks back to me.”

Their love affair goes back a few years, when Watson delivered a yak to a ranch in Ridgway, Colo., (that’s another story for another time.) Carlos was 3, and the two hit it off immediately.

“He put his big head over my shoulder and we got to be friends. We kind of bonded,” Watson said.

He told Carlos’ owners that he’d always have space for the camel, which has a life expectancy of 40 to 50 years. Two years later, Carlos arrived at the Spring Brook Ranch, where Watson and his wife, Carol Bibler, raise yaks. Bibler wasn’t particularly pleased, nor were their mules and horses.

“The horses and mules were terrified of him. They ran to the far side of the paddock and stayed there for three days,” Watson said. “It took days for them to get acclimated.”

Watson and Bibler weren’t sure what to do with their two-humped Bactrian camel, who’s now 7 years old. He half jokes that he thought Carlos was Mexican, given his name, so his first commands were in Spanish. That didn’t work so well, perhaps because Carlos had zero training. That was an issue with the then-1,750-pound camel. But Watson knew Carlos was smart.

“Camels are different than any animals I’ve worked with: horses, mules, donkeys, yaks and dogs,” said Watson, who grew up on a cattle ranch in rural Mississippi. “Camels are smarter than all of them except for dogs. You can train them all, except for spouses. None of us is successful at training spouses.”

Today, Carlos knows basic terms for starting, stopping and lying down.

“I’d use the command ‘koosh’ to lie down, and he did OK,” Watson said. Then he and Bibler traveled to Mongolia for a fishing trip, and Watson claims he had an epiphany. “We realized we were giving him the commands in Arabic, but that’s for dromedary Arabian camels. No wonder he was confused. He’s Mongolian. So I tried ‘sook’ and he does much better now.”

Carlos has educated the crew in many more ways. Bibler said they like to learn about their livestock and their cultures, and the couple have become a walking Wikipedia when it comes to Bactrian camels, which hail from the Gobi desert, the steppes of Mongolia and Russia.

The weather there can vary from 40 degrees below zero to 122 degrees, with temperature changes fluctuating by as much as 60 degrees in a day. They like a semi-arid environment, and can go for a week without water and two weeks without food.

“But I don’t think Carlos could do that. He’s fat,” Watson said, proudly patting the camel’s side.

They have three eyelids over their big brown eyes, with two rows of eyelashes that most women would die for, and narrow nostrils that shut tight, all features adapted to help them withstand sandstorms. Their eyes continually weep to flush them out.

Watson notes that horses have prehensile upper lips, which means they’re adapted for grasping or holding. Camels have both upper and lower prehensile lips, which means Carlos’ lips are like three fingers to even better grasp food.

“He’s an expert at stripping leaves off limbs,” Watson said.

Like cows, camels are ungulates with four stomachs. Feeding Carlos a zucchini is like pushing it into a Veg-O-Matic, according to Watson. Like cattle, camels grind and swallow their food, then burp it up to better chew it later. Watson said this internal combustion helps them stay warm in the winter “like a compost pile,” but it also has another use.

“Camels will spit on you, spraying saliva, but if they get really upset they’ll burp up their cud and lay that on you,” he says, laughing again. “You might have to wash your clothes more than one time to get the smell out. And he’s got the worst breath of any animal I’ve ever known.”

Carlos is a “full-on vegetarian,” Watson added.

“He likes everything but kale. He and I are both burned out on kale,” Watson said. “I grew some in the garden and we both grew sick of it. He would turn his head to say ‘No more.’ ”

With their massive size they can be intimidating. If Carlos starts to get in Watson’s space, he raises his arms and Carlos immediately backs off.

“It’s universal with camels, even with dromedaries,” Watson aid. “I’ve watched videos, and when one starts bucking and carrying on, everybody’s arms go up automatically.”

Carlos has been gelded, because otherwise he could be subjected to “Berserk Male Syndrome,” which Watson said is a form of aggression among stud camelids — including alpacas and llamas — when they come into musk and are ready to breed.

They also can love people a little too much, with Watson and Bibler noting how camels are so flexible they can wrap their necks around people and accidentally crush them.

Yet despite their size, camels form close bonds with people, and are known for their noble dignity and a wicked sense of humor. Watson has ridden Carlos once, and often sits or leans on him when he’s lying on the ground. He hopes to eventually ride Carlos more often, noting how comfortable the ride is nestled between the two humps, almost like gliding on a gentle porch swing.

“The humps are a natural saddle; it’s a very secure seat,” Watson said. “And they’re so big they can’t buck very hard. You just grab the hump and hang on.”

He likes to ask people if they know what the purpose is for the humps, and broadly laughs when most people guess that they store water. Instead, the humps are for fat reserves, and it’s not unusual for one to flop over.

Watson and Bibler, who regularly pack horses and mules into the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area, also have outfitted Carlos with a pack. He can handle about 450 pounds, compared to about 250 for a mule. But they won’t take him into the wilderness because he scares horses.

“We pack, so we’re really sensitive to that,” Watson said. “If somebody ran into a camel in the middle of the Bob, it would be bad.”

Carlos does have a day job, educating the students at Ruder Elementary School in Columbia Falls when they swing by on a field trip.

Bibler said they limit visits only to the children in that school because otherwise it overwhelms the ranch.

“We’re completely booked, so we don’t do other schools,” Bibler said. “We get deluged with phone calls and it’s hard to say no, but we are a working ranch and it takes a whole day to prepare for the students.”

Their ranch is not open to the public, Watson added.

After working with Carlos for about an hour, Watson removes his size large halter — borrowed from one of the mules — and turns him loose on the lawn, where Carlos wanders off to graze while Watson and Bibler turn to their other ranch chores.

It’s a good life for the camel, but Watson makes sure that Carlos knows his place.

“We ate camel stew when we were in Mongolia, and it was quite tasty,” Watson said, flashing his sly grin once again. “That’s what I keep telling Carlos when he’s bad — you could end up in the freezer.”

(TNS)