MOSCOW - The last time Keith Hendrick spoke with the Lewiston Tribune, it had been 10 years since his son vanished. Ten years full of unanswered questions and dead-end leads. Ten years of heartache.

"You always say 'If somebody ever did anything to my kid, I'd kill 'em,' " he said in a 2008 interview about the murder of his son, Wil. "We've all said that. But when the time comes, the hurt is so great, you don't even think about that."

Keith Hendrick will never see his son's killer brought to justice. He died last year at the age of 75. But the case is still being actively investigated, with a new tip coming earlier this year.

"But it was nothing that was fruitful," Moscow Police Chief David Duke said. "But as time changes, people do have time to reflect and maybe have a moment where they want to see if they can make a difference."

Duke and Latah County Sheriff Wayne Rausch discuss the case frequently, and are in the process of looking at the physical evidence and maybe resubmitting it to the state crime lab for analysis with newer technology. Rausch was a detective in the sheriff's office when Hendrick disappeared, but was taken off the case by then-sheriff Jeff Crouch.

"He wouldn't let me get involved in it whatsoever, to the extent that he actually pass-coded the case file and I couldn't even access my own reports," Rausch said. "There was a long period of time when I was in patrol, before I became sheriff, that I didn't even know where the case was at."

When he took the reins of the sheriff's office in 2004, Rausch said he was "absolutely stunned" at the lack of follow-up in the case. He still thinks it is solvable.

"It's not forgotten," Rausch said. "It's a cold case, but it is still being worked."

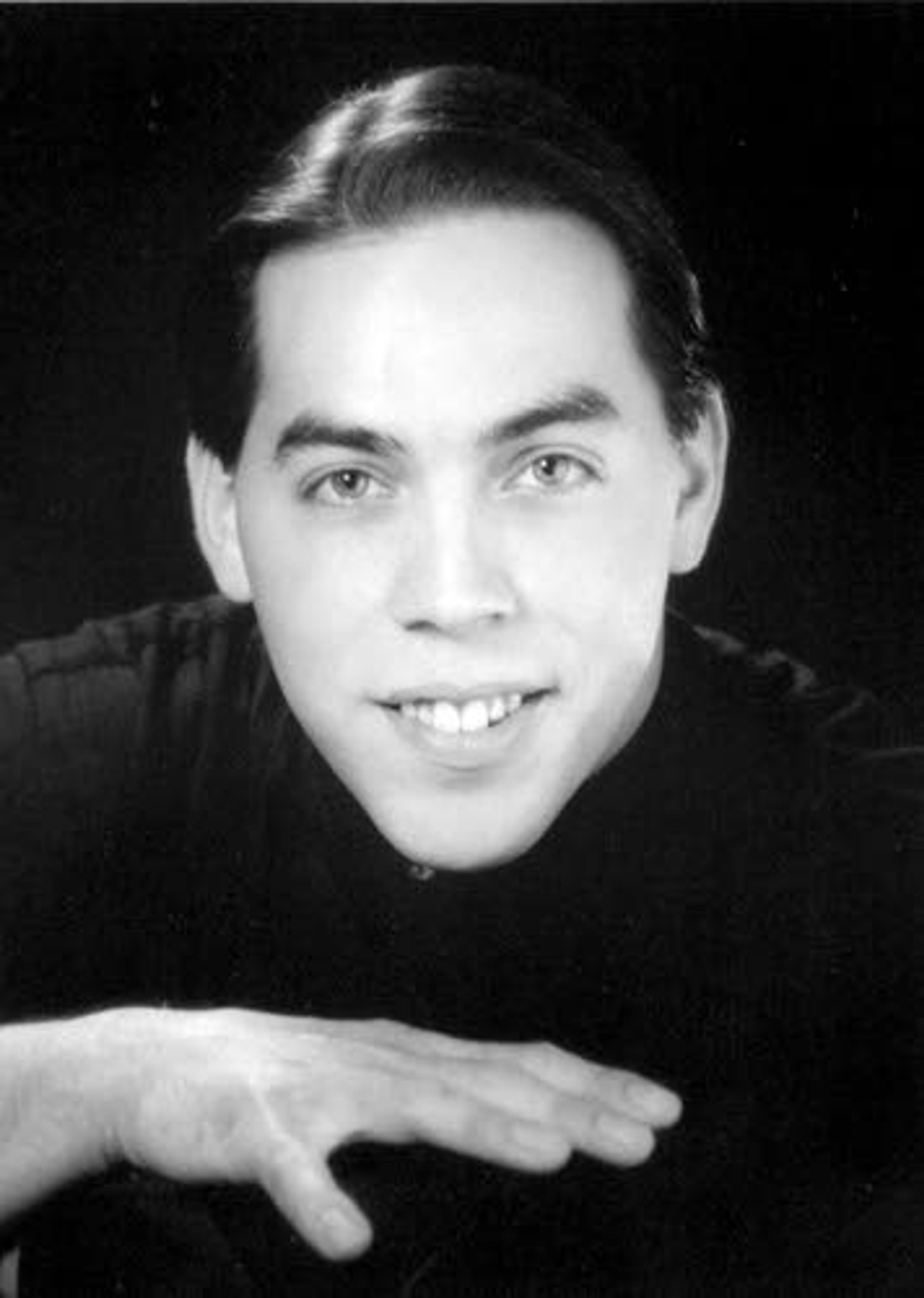

Wil Hendrick was a 25-year-old University of Idaho theater student when he disappeared in January 1999. He was classified as a missing person until his skull and jawbone were found by hunters three and a half years later in eastern Latah County.

Investigators developed several suspects in 1999. But without a body or a crime scene, the trail quickly went cold, former Moscow Police Chief Daniel Weaver said in 2008.

"The most critical part of a case is the first 48 hours," Weaver said while recapping the case over a cup of coffee in the police department conference room. "After that, evidence starts to deteriorate and dissipate."

So the investigation into Hendrick's disappearance started the way most missing persons cases do: interviews with the people who saw him last.

"It was a cold morning on Jan. 10, 1999," Weaver recalled. "I was at the station for some reason, probably to pick something up. I was just heading out the door when Jerry Schutz came in. He said, 'Hey, my partner is missing.' "

Hendrick had been at a party the night before at an apartment on C Street. But Schutz said he never made it back to their home in a trailer court just north of town.

Schutz was worried that Hendrick had gotten drunk, cut across some fields and fallen in a ditch, Weaver said.

Schutz and some friends spent the day looking for Hendrick, along with police and sheriff's deputies. Hendrick's car was found about a day later, parked near Friendship Square in downtown Moscow with the keys left in the console.

"We went through the car, and found nothing unusual," Weaver said.

Interviews with people at the party raised some questions, but ultimately led to the first set of dead ends.

"There was some activity that you could say was maybe somewhat suspicious, but not out of the ordinary at a party," Weaver said.

Hendrick had apparently gotten intoxicated and into a "heated conversation" with some people there. But interviews and polygraph tests of those people, plus searches of their homes, turned up nothing.

Other people at the party remember Hendrick's car parked out front. They also reported hearing a car, possibly Hendrick's, leaving the party at a high rate of speed, throwing gravel in its wake.

Another early suspect was the man who lived below the party. He told police he was asleep when Hendrick wandered into his apartment, "mumbling and talking tough," Weaver said.

"As strange as that would sound to many people, it's not uncommon," he said of drunks stumbling into the wrong home.

Hendrick was tall and was known as a person who liked to fight, and was good at it. But the man told police that he simply turned Hendrick around and sent him out the front door. A search of the apartment turned up no physical evidence, and the man wasn't pursued as a suspect.

But it turned out that he was the last person interviewed by police who saw Hendrick alive.

The next couple of years were filled with hundreds of tips and reported sightings nationwide, including Florida and Las Vegas. The national press latched onto the story because Hendrick was gay, and he disappeared about a year after Matthew Shepard was beaten to death in Wyoming because he was gay.

Keith Hendrick said he didn't know if his son's sexual orientation played into his death. But he added that Moscow is generally a gay-friendly town.

"(Wil) really liked Moscow," Keith Hendrick said. "A number of people from the gay community showed up to help with the search."

One of Hendrick's friends said the Moscow gay community was put on edge by his disappearance.

"There was certainly fear," Katherine Sprague, owner of the Safari Pearl comic book store, said in 2008. "There was a lot of disbelief, and a lot of uncertainty. And there was an awful lot of speculation."

Rausch developed perhaps the most solid lead in the case. It centered around a truck driver who lived in the same trailer court as Hendrick and Schutz.

"Nothing about what this guy did or said ever really made any sense," Rausch said.

Rausch got a tip from a woman he knows that the truck driver called and told her that he wanted to get his things out of his trailer, and that he was leaving town for Florida. Hendrick would sometimes crash at the man's house when he was out late so he wouldn't have to come home and get into a fight with Schutz, Rausch said.

So when he found out the man suddenly wanted to leave town, Rausch took notice.

"It was highly suspicious activity," he said. "Unfortunately, there wasn't enough information for us to ever really compel him to come in and do an official interrogation. I was very, very frustrated over the fact that I couldn't do anything more with it."

Weaver said the man was tracked down in Florida, but he never cooperated with the investigation. His trailer was searched, but no evidence was found.

"Could he have done it? Sure," Weaver said. But with no definitive evidence, that suspect couldn't be further pursued, he added.

Rausch said the man could be the one that got away.

"To this day, I still believe that if he wasn't specifically involved in it himself, he knows who was."

Weaver said he hoped a little more public attention to the case would finally help shake something loose.

"Obviously, somebody out there knows something. We're hoping that one of those folks will come forward and give us some information to solve it. It's an open case and will remain so until it's solved."

Moscow police Detective Dave Lehmitz agreed when he spoke to the Tribune in 2008. "The majority of the time, that's how these cases are solved. Someone comes forward."

But Keith Hendrick, a law enforcement officer himself for 38 years, understood that not all homicide investigations are slam dunks.

"Most officers have a case like that, that sticks in your craw because you couldn't solve it," he said. "You just have to have something to work with."

Weaver said the Hendrick case does that to him.

"It's one of the most frustrating things that agencies experience, when they have a case, especially a major case, that they can't solve."

Keith Hendrick said each holiday season was tough, not because it's the time when his son vanished, but because his birthday was Christmas Eve. He and Wil's mother, Leslie Hendrick, tended to mark that day, and the day his remains were found.

And while he said he wasn't vindictive over the fact that his son's killer hadn't been brought to justice, Keith Hendrick worried that the person remained free to hurt others.

"A lot of people that kill somebody and get away with it, they'll kill another one or two in their lifetime," he said. "We know the good Lord will take care of this one, but we'd like to get him caught so he doesn't do any more."

Mills may be contacted at jmills@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2266.