Jacob Waller sticks his ungloved hand, cellphone first, into the head-sized hole in the catalpa tree. The bees inside seem to ignore him, even when the flash goes off.

But the photos tell him the hole is probably 2 feet high and the swarm is huge.

He has used two ladders, one to haul the second one higher into the tree where it can be wedged into the lowest crotch, maybe 25 feet above the ground in a tree that could be 100 feet tall. From there, he maneuvers his body around the trunk to a fairly secure seat on a thick branch.

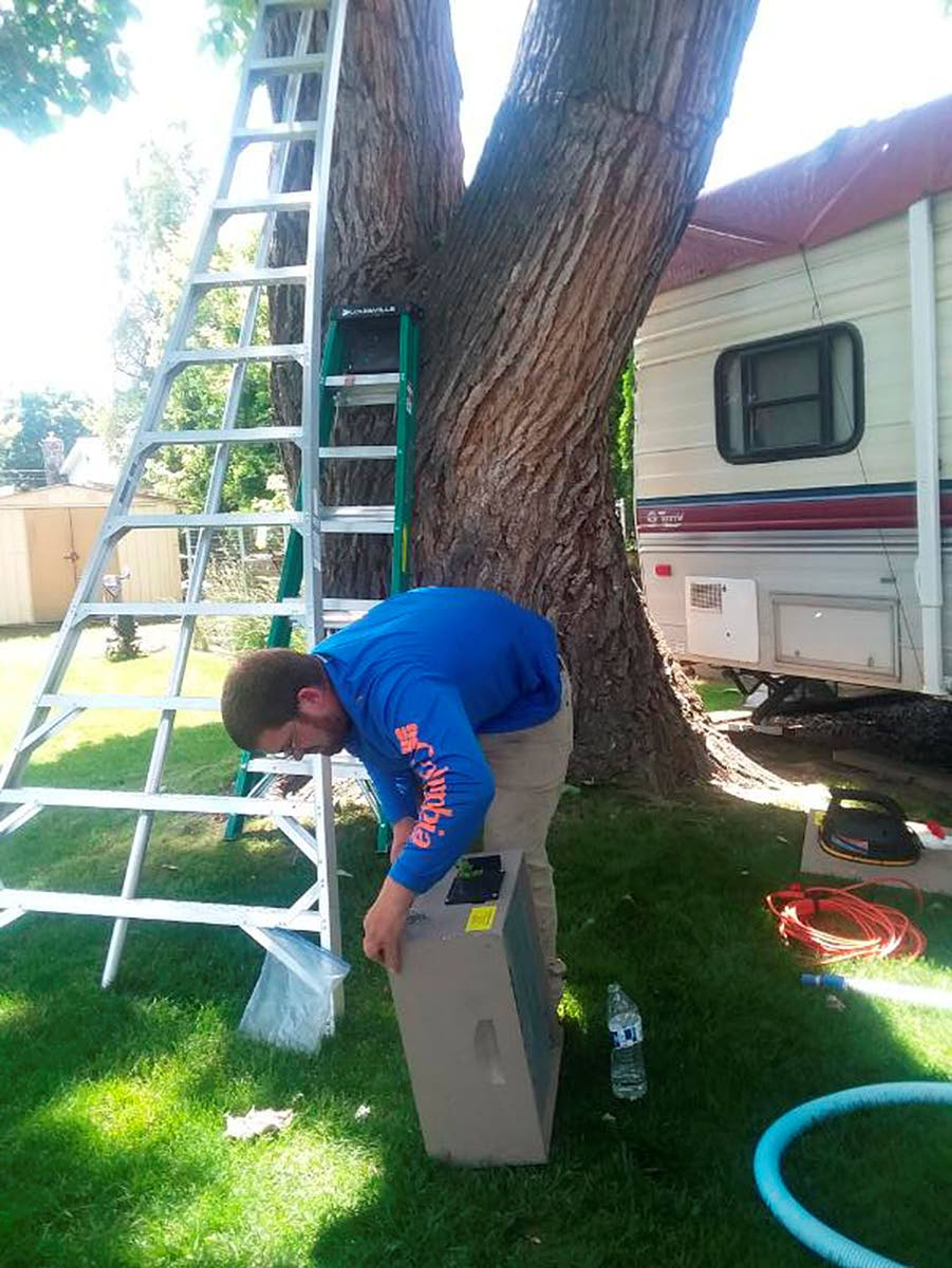

The vacuum box comes up next. He bought the lid with a specially modified vacuum attachment, not a regular vacuum cleaner because that kind of suction would kill most of the bees, he says. The lid fits on a box that matches the dimensions of the bee hives that are common in fields around the countryside. But this box has a bottom that is screened and slides in and out of grooves on each side.

Waller is in street clothes, not the white bee suits that protect beekeepers from their stinging livestock. Most of the time he doesn’t need one, because the swarm is focused, he says. “They are docile until you mess with them.”

At 23, he has a fair amount of experience with bees and their swarming habits. He got his first personal hive at his Clarkston home two years ago but has been studying them for twice that long, he says. His long-term goal is to be a honey producer, ship hives to areas that need pollinators, and sell starter hives to beekeepers.

Right now, he’s just increasing the number of hives he cares for, sometimes by splitting healthy hives into two, other times by catching swarms that now number 21, counting the one in the catalpa tree in a Lewiston Orchards backyard.

Bees swarming is as natural as the honey they produce. It’s part of their natural reproductive cycle, Waller says.

Usually in May or early June, they start feeling crowded and the resident queen gathers together about half her workers and takes off in search of a new home. She leaves behind fertilized eggs, one of which will become the new queen bee in her old hive.

The swarms that most people see are in transit. They cluster for a few hours or a day on a branch or a fence post or even a vehicle while scout bees spread out ahead of them.

The catalpa tree swarm likely thought it had found its new home.

It was discovered when the couple walked into their backyard on a Sunday morning and heard a loud buzzing coming from overhead. They finally located its source by the number of bees pouring in and out, mostly in.

A neighbor knew of the Valley Beekeepers Association and a couple of telephone calls brought Waller and his equipment to the home.

Fortunately, the couple stayed calm and didn’t attempt to dislodge the bees by spraying them with water or chemicals, which could have threatened their survival, he says.

Sometimes he’s lucky and the swarm is centered on a branch that can be shaken hard enough to dislodge most of the bees into a catch box. The hardest are the ones that have already decided on a home in the wall of a building. He’s cut out two of those this year.

In any case, the goal is to get the queen into the catch box by carefully running the vacuum tube around the inside of the tree. Then he opens the box slightly, sits back and watches for several minutes. If more bees are going in than coming out that means the queen is inside. Then he closes it up.

At home, he will weigh the catch box with its swarm, then set it on top of an empty bee hive, pull the slide tray open and tap on the top so the bees fall into their new home. Usually they stay and will begin building comb immediately.

And he was right about the swarm being huge, Waller says. It weighed in at more than 4 pounds of bees.

Lee is an avid gardener and a retired Lewiston Tribune reporter. If you know of or have a special garden or yard, you can let her know at sandra.lee208@gmail.com or call Close to Home Editor Jeanne DePaul at (208) 848-2221.