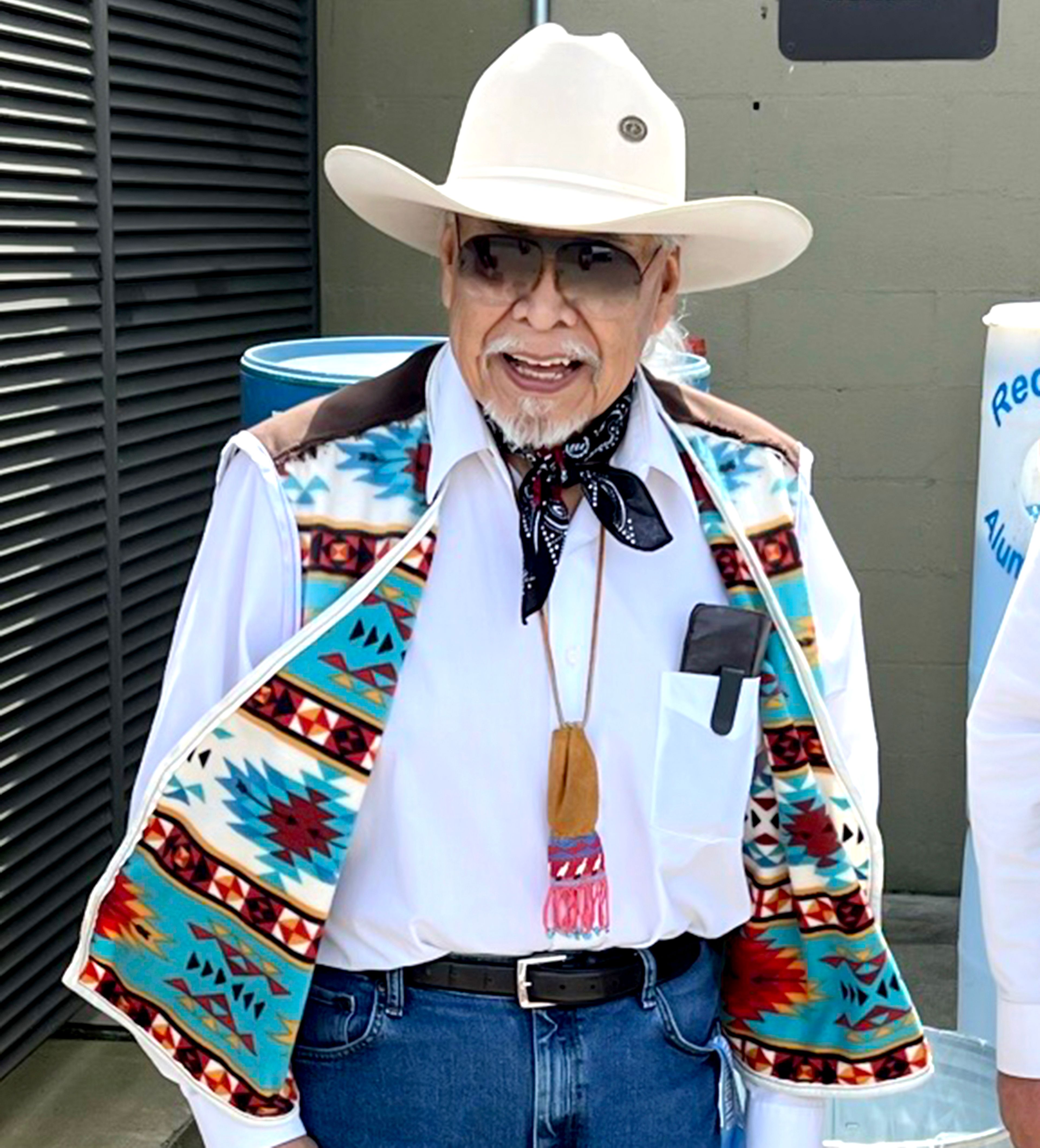

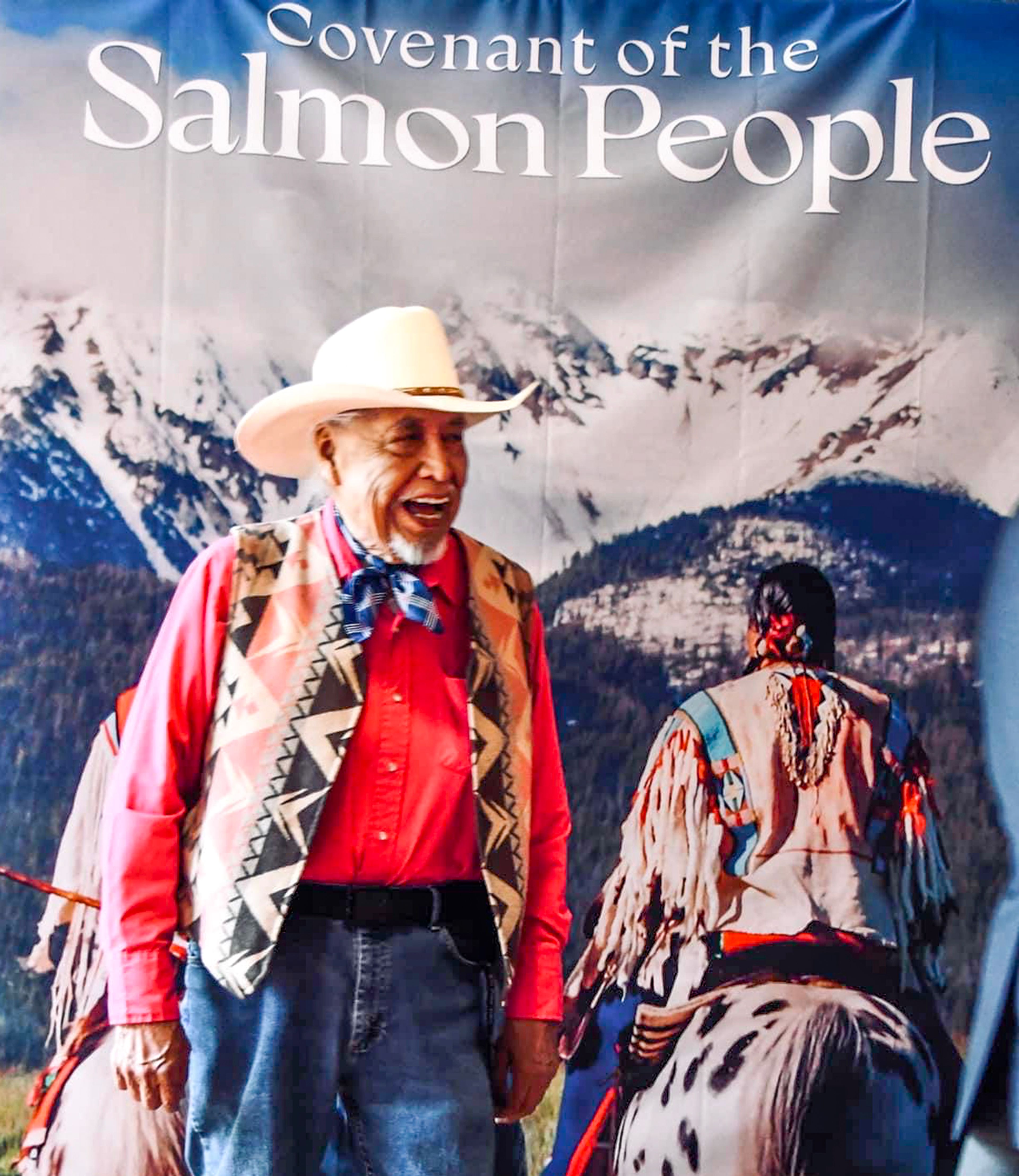

Silas Whitman helped build the Nez Perce Tribe Department of Fisheries

Silas Whitman, leader of the Nez Perce Tribe's Fisheries Department, revived Snake River's chinook and coho populations

Anglers enjoying the fall chinook and coho fisheries in the Snake River Basin may not know it, but they owe a debt to Silas Whitman.

He didn’t do it by himself, but Whitman, who died Oct. 1 at the age of 82, envisioned those fisheries at a time when many fish managers likely considered them pure fantasy. Snake River coho were extinct and fall chinook — that numbered in the dozens above Lower Granite Dam — were circling the drain and soon to be protected by the Endangered Species Act.

Whitman, a member of the Nez Perce Tribe and former director of its Department of Fisheries Resources Management, pushed and cajoled outside entities to gain funding to build hatchery programs for the two anadromous species, and recruited, inspired and led a team of fisheries professionals to put in place the infrastructure and philosophy that eventually made those dreams and others a reality.

To do it, Whitman built a world-class fisheries department at the Nez Perce Tribe. He hired a cadre of eager, young biologists from outside the tribe and, at the same time, he recruited and inspired a generation of tribal youth to work first as interns and then to get their degrees in fisheries and return to the tribe as talented biologists and managers.

“The guy was just an empire builder,” said David Johnson, director of the tribe’s Department of Fisheries Resources Management.

Whitman wasn’t satisfied with a few fisheries on mainstream rivers like the Clearwater, Snake and Salmon. He pushed for habitat restoration in tributaries throughout the Nez Perce homeland — the “usual and accustomed” fishing places mentioned in the tribe’s 1855 treaty with the U.S. government.

“He would tell us, you know, ‘For us to be Nez Perce, we have to have fish. In order to have fish, you have to be able to take care of those fish such that those fish can take care of you,’” said Joseph Oatman, deputy manager of the department and director of its harvest division.

In the late 1980s, Johnson said tribes in the Columbia River Basin were just starting to gain some real recognition, funding and acceptance in matters of fish and wildlife management. Events like the Boldt decision of 1974, the confrontation between the Nez Perce Tribe and state of Idaho at Rapid River in 1980 and passage of the Northwest Power Act the same year all worked to affirm the rights of the Nez Perce and other Columbia River Tribes and tribes throughout the Pacific Northwest to not only harvest an equitable share of salmon, but also to be co-managers of fish and wildlife resources within their traditional homelands.

That was the setting in which Whitman took over the department. While financial resources were available in theory, they still had to be fought for and justified using sound science. For that, the tribe needed a robust fisheries department.

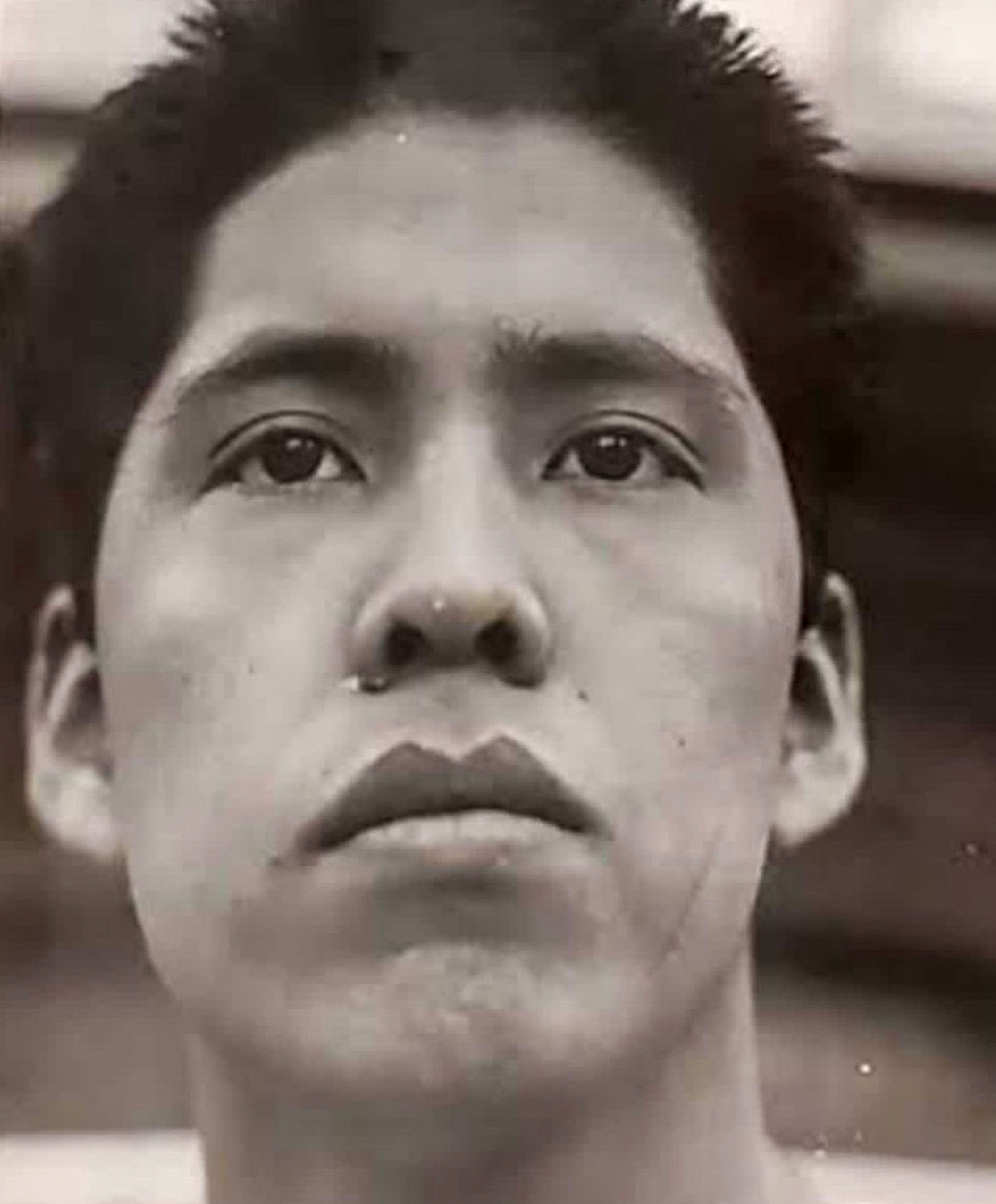

When Whitman started as director in 1987, it was tiny.

“I think the program might have been maybe half a million dollars, with maybe 12 or so people. And when he left in 1999 I think there were like 200 employees, and it was a $15 million program,” said David Johnson.

Whitman had connections throughout the region and, if there was someone in a position of influence, like a governor or member of the power council, that he didn’t know, he met them.

“Just by his pure physical presence, he was someone that carried so much seriousness and gravitas, I guess, and people would listen to what it was that he had to say,” Johnson said. “He just instilled that respect. And he used that. He used his abilities to the utmost to take advantage of the resources and the rights and develop this program that he knew the tribes, and the Nez Perce specifically, could do a good job with.”

Within the department, Whitman instilled a sense of mission and created a family-like work environment. Becky Johnson, now the production director of the department, was hired as a biologist right after she graduated from Eastern Washington University. A professor, who viewed salmon in the Snake River as a lost cause, questioned her choice.

“The fall chinook were almost gone. But you walk into this environment and Si is like, ‘We’re going to put them back,’ and that was in the ’90s before we had a hatchery. We had zero hatchery programs,” she said.

Getting funding and approval for what is now the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery at Cherrylane was one of their big pushes. But the idea had detractors. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game opposed it, as did others in the basin.

“It was like against all odds,” said Becky Johnson.

Whitman drove them to write a hatchery plan and the scientific justification for it, and then to travel across the Northwest with him to advocate for it.

“He was just a road warrior during that time and he drug us all (along). We were at every Power Council meeting, testifying, presenting and everything,” she said. “It was really quite remarkable that we were able to build that facility and operate that facility because it didn’t have a lot of support regionally.”

The hatchery now produces some of the fall chinook that return to the Clearwater, Snake and Salmon rivers. It’s part of a larger fall chinook program upstream of Lower Granite Dam championed by the tribe and one of the tribe’s many hatchery programs.

When the tribe had an opportunity to obtain surplus coho eggs, Whitman was all in. But there was strong outside opposition. Idaho feared coho would bring fish disease to the basin.

“The state of Idaho said they would arrest us at the state line,” Becky Johnson said. “And so he called his friends at the Yakama Nation and developed a plan to have tribal members drive them to the state of Idaho.”

They did. There were no arrests but Idaho and fisheries officials in Washington later sent letters insisting that the eggs be destroyed. Whitman and the tribe ignored them. It took decades, but eventually the coho run strengthened. Today, coho and fall chinook are a robust part of the fall fishery for tribal and non-tribal members alike.

While Whitman was in those contentious meetings with state or federal officials, he often had young tribal members at his side. Oatman, now deputy manager of the department and director of its harvest division, knocked on Whitman’s door as a recent high school graduate in 1992. He told Whitman he came from a fishing family, was headed to the University of Idaho to study fisheries and wanted to work for his tribe.

“He smiled and he said, ‘Yeah, we’ve got a place for you here’” Oatman recalled.

Jack Yearout, another 1992 graduate, also found himself working in fisheries as did other young tribal members like Aaron Penny and Mike Tuell — all part of an intern program started by Whitman.

“We were able to kind of sit in some of these meetings and listen to what was going on at the time, and it really kind of instilled, certainly in me and I think the others, that what we’re trying to do here is something significant,” Oatman said.

Yearout said they might not have understood all the details of those high-level discussions, but being exposed to them would pay off years down the road.

“He knew that at some point in the future, you guys are going to need to be able to do this,” he said. “Fast forward, and now I sit in meetings with Idaho, and other states, or anybody, and it’s not a big deal, because he’d prepared us for that 20 years ago.”

Yearout sees Whitman’s vision to recruit young tribal members to study fisheries science as a huge part of his legacy.

“As Joe (Oatman) said, you take care of the fish and they take care of you. That was his legacy. So it’s really really neat to see where we’re at and, you know, I think we can go a lot further and do a lot more.”

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.