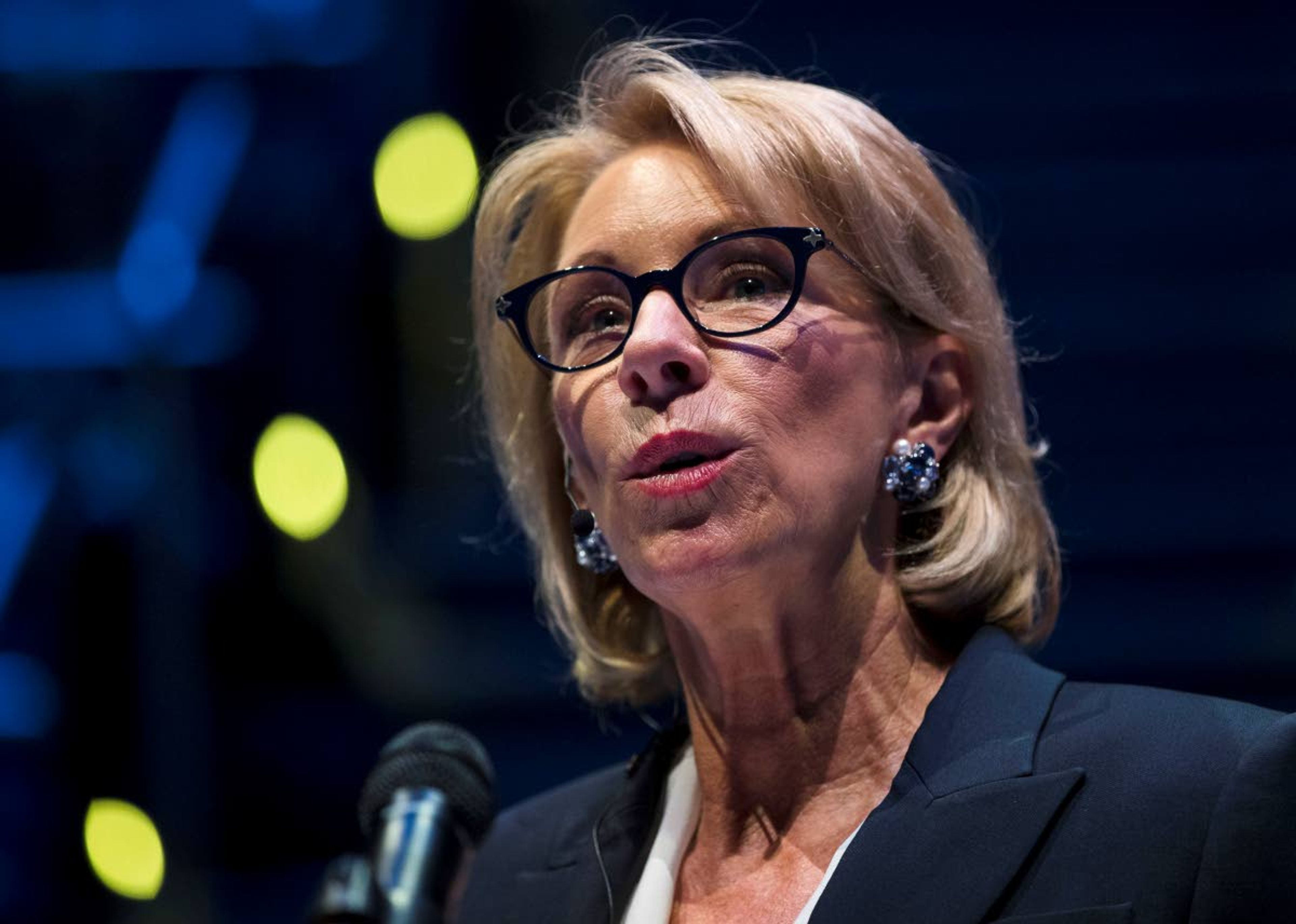

Betsy DeVos changes campus sexual misconduct rules

Education secretary moves to strengthen rights of the accused, give colleges more flexibility in cases

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos unveiled sweeping changes Friday to campus sexual misconduct rules that would bolster the rights of the accused and give colleges more flexibility in how they handle Title IX cases.

The long-awaited rules make key changes to former guidelines from the Obama administration, including a tighter definition of sexual misconduct, reduced responsibility for colleges to investigate complaints, and the right for advisers on all sides to cross-examine those involved.

DeVos said her aim was to restore fairness and rebalance the rights of the accuser and accused in the contentious arena of campus sexual assault. As more victims step forward to report cases, emboldened by a more supportive national environment, hundreds of alleged offenders across the nation have fought back with lawsuits saying that colleges violated their due process rights by rushing to unfair judgments.

“Throughout this process, my focus was, is, and always will be on ensuring that every student can learn in a safe and nurturing environment,” DeVos said in a statement. “That starts with having clear policies and fair processes that every student can rely on.

“Every survivor of sexual violence must be taken seriously, and every student accused of sexual misconduct must know that guilt is not predetermined,” she said. “We can, and must, condemn sexual violence and punish those who perpetrate it, while ensuring a fair grievance process. Those are not mutually exclusive ideas. They are the very essence of how Americans understand justice to function.”

Title IX prohibits sex discrimination in education by schools that receive federal funding. It is mainly relevant to higher education but also covers K-12 schools, although DeVos made distinctions between them in her proposed rules.

The rules drew immediate, sharply divided reaction. Some hailed the changes as long overdue. Others condemned them as a rollback of protections that would make it more difficult for students to report sexual assault and easier for colleges to ignore them.

Jess Davidson, interim executive director of End Rape on Campus, said the proposed rules were “worse than we thought.”

“It will return schools to a time where rape, assault and harassment were swept under the rug,” Davidson said in a statement.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein expressed fears that the rules would silence victims and endanger students. “We refuse to let this administration drown out the voices of victims in favor of their accusers,” the California Democrat said in a statement.

Suzanne Taylor, the University of California’s interim systemwide Title IX coordinator, said in a statement that the “proposed changes will reverse decades of well-established, hard-won progress toward equity in our nation’s schools, unravel critical protections for individuals who experience sexual harassment, and undermine the very procedures designed to ensure fairness and justice.”

Supporters said the rules would better ensure fairness in proceedings they believe have become too skewed against the accused.

“Finally they’re issuing rules to reinforce the rights that already are well established and should be uniformly applied,” said Mark Hathaway, a Los Angeles attorney who has represented more than 150 students accused of sexual misconduct. “It’s been a long time coming.”

The proposed new federal rules would for the first time require colleges and universities to allow cross-examination during mandatory live hearings in misconduct cases, though parties would not question each other directly. Both sides would have equal opportunity to present witnesses and access evidence. And the person who makes the ultimate finding could not be the same person who investigated the complaint, addressing widespread criticism that Title IX coordinators often act as prosecutor, judge and jury.

Hathaway said California courts already have begun ordering colleges to restore due process rights to accused students. In recent cases against Claremont McKenna College and University of California, Santa Barbara, he said, the state appeals court said that respondents had the right to question their accusers.

Taylor, however, said in an interview that the prospect of cross-examination, probably by an attorney, would intimidate victims and witnesses and discourage them from speaking up.

The new rules also would adopt the U.S. Supreme Court’s definition of sexual harassment, which requires conduct to be so severe, pervasive and “objectively offensive” that it effectively denies a person equal access to the school’s education program or activity. Obama-era guidelines defined sexual harassment only as “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature” that was so severe or pervasive that it denied or limited access to education. They did not require the conduct to be objectively offensive or deny access.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, which promotes free speech on campuses, welcomed the narrower definition. It would eliminate the “confusion that has led institutions nationwide to adopt overly broad definitions of sexual harassment that threaten student and faculty speech,” said Samantha Harris, a foundation vice president.

But Taylor said the change would sharply reduce victims’ ability to win justice.

She said she also was concerned that the regulations reduce colleges’ responsibility to respond to complaints, requiring it only if authorities had “actual knowledge” of misconduct within their programs or activities. Currently, colleges are held responsible for investigating misconduct they know or should know about even if it occurs off campus — if the assault affects the victim’s education.

Colleges also would have the option under the rules to choose to adopt a higher burden of proof — clear and convincing evidence — to reach a finding of sexual misconduct. They could continue to use the current lower standard of a “preponderance of evidence” only if they also used it in other campus misconduct cases. The 10-campus UC system will continue to use the current standard, Taylor said.

TNS