Massive cash injection

Drug industry spent millions to squelch talk of high drug prices

Facing bipartisan hostility over high drug prices in an election year, the pharma industry's biggest trade group boosted revenue by nearly a fourth last year and spread the millions collected among hundreds of lobbyists, politicians and patient groups, new filings show.

It was the biggest surge for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, known as PhRMA, since the group took battle stations to advance its interests in 2009 during the run-up to the Affordable Care Act.

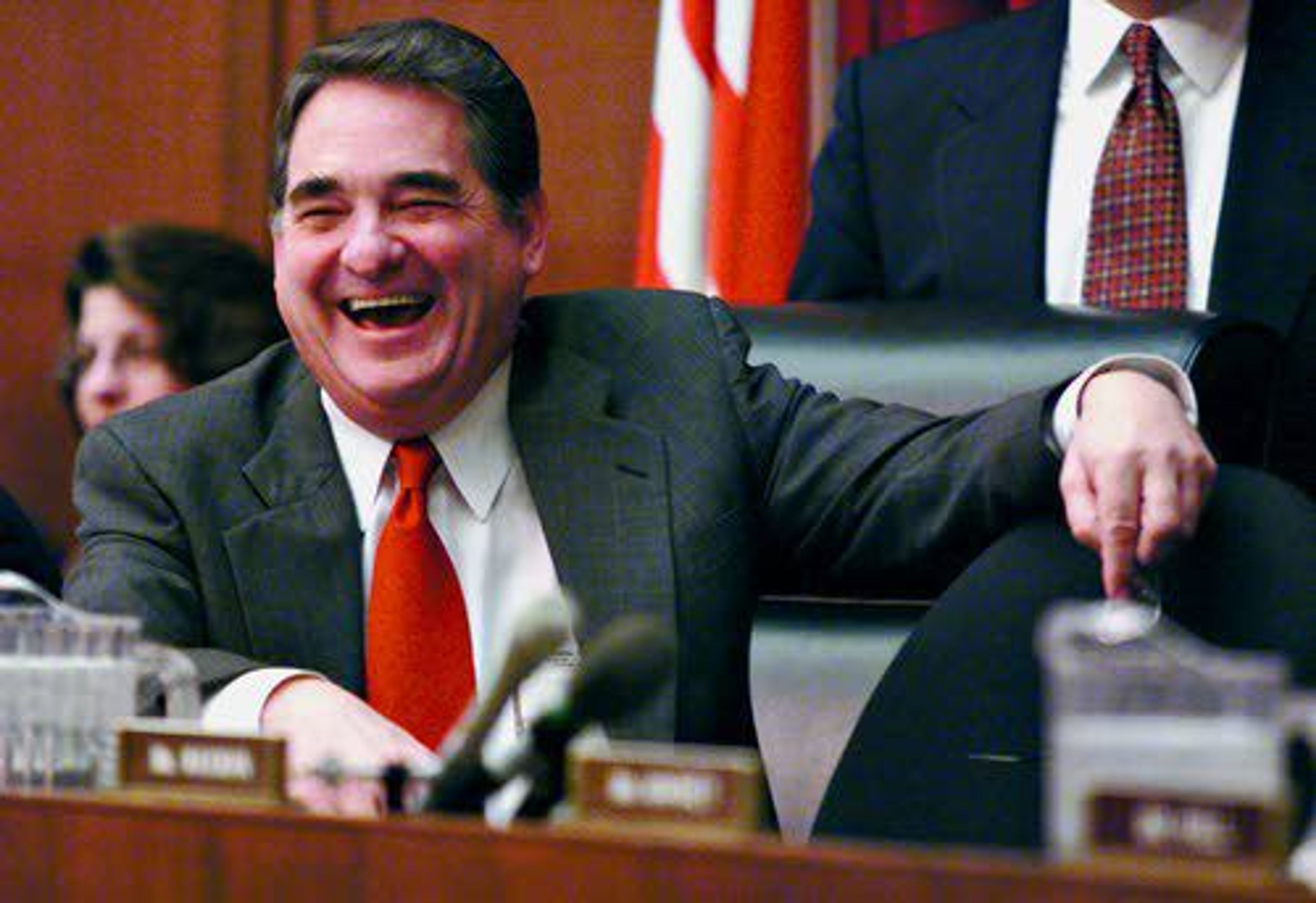

"Does that surprise you?" said Billy Tauzin, the former PhRMA CEO who ran the organization a decade ago as Obamacare loomed. Whenever Washington seems interested in limiting drug prices, he said, "PhRMA has always responded by increasing its resources."

The group, already one of the most powerful trade organizations in any industry, collected $271 million in member dues and other income in 2016. That was up from $220 million the year before, according to its latest disclosure with the Internal Revenue Service.

PhRMA spent $7 million last year to prepare its ubiquitous "Go Boldly" ad campaign and gave millions to politicians who were up for election in both parties in dozens of states. It lavished more than $2 million on scores of groups representing patients with various diseases - many of them dealing with high drug costs.

Some of the biggest patient-group checks went to the American Autoimmune Related Disease Association, for $260,000; the American Lung Association, for $110,000; the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, for $136,150; and the Lupus Foundation of America, for $253,500.

PhRMA also gave big money to national political groups financing congressional, presidential and state candidates. The conservative-leaning American Action Network got $6.1 million. The Republican Governors Association got $301,375. Its Democratic counterpart got $350,000.

PhRMA's state and federal lobbying spending rose by more than two-thirds from the previous year, to $57 million.

"That's PhRMA. They do it all," to protect drug companies from potential policy risks, said Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks political financing. "And they're going to marshal even more resources when they perceive that these threats or opportunities are most imminent."

Threats seemed especially dire last year. Storms of bad publicity hit the industry in the form of stories about arrogant executives and thousand-dollar pills.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton said some pharma companies were "making a fortune off of people's misfortune." Then-candidate Donald Trump, a Republican, suggested he could save $300 billion annually by requiring drugmakers to bid on business.

Nonprofit organizations such as PhRMA must file detailed disclosures with the IRS. PhRMA, which submitted its 2016 report in early November, shared a copy with Kaiser Health News.

The group also aimed dollars at states where policymakers were considering drug-related measures such as price limits or greater price transparency, the document shows.

It gave $64 million to a California fund established to defeat a proposal requiring state agencies to pay no more for drugs than does the federal Department of Veterans Affairs. Also supported by direct contributions from drug companies, the fund spent $110 million last year to defeat the initiative, California regulatory filings show.

This year, California established a less comprehensive law requiring drug firms to give notice and explanation when they substantially raise prices. PhRMA recently sued to block that measure.

In Louisiana, where policymakers were considering proposals to make drug prices clearer to consumers, PhRMA gave campaign contributions directly to scores of state legislators last year. The group also gave hundreds of thousands of dollars to help defeat a ballot proposal for single-payer health care in Colorado.

Last year's massive mobilization underscores how besieged the industry felt over complaints about soaring medicine prices and high profits.

PhRMA's $271 million in revenue for the year represented its biggest budget since 2009, when it recorded $350 million in dues and other revenue.

The $57 million it spent on lobbying was also the most since 2009, when the lobbying bill was $70 million. So was the $7 million spent on advertising, a cost that should rise this year, since the "Go Boldly" ads aired in 2017. PhRMA employed 237 people last year, up from fewer than 200 in 2011.

The association's 37 members include the biggest and best-known drug companies including Johnson & Johnson, Celgene, Merck, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Amgen. Holly Campbell, a PhRMA spokeswoman, declined to make an executive available to discuss the report, saying it doesn't comment on contributions.

"PhRMA engages with stakeholders across the health care system to hear their perspectives and priorities," she said in an email. "We work with many organizations with which we have both agreements and disagreements on public policy issues."

Patient groups receiving PhRMA money often deny it influences their policies or keeps them from criticizing high drug prices.

The Lupus Foundation has policies to ensure there is no conflict of interest, a spokeswoman said. At the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, donors such as PhRMA "have no role" in the group's decision-making process, a spokeswoman said.

"No funder influences our position, agenda or science-based messages" at the American Lung Association, its spokeswoman said.

The American Autoimmune Related Disease Association did not respond to requests for comment.

During negotiations over Obamacare, PhRMA agreed to support overhauling health care relatively early in the process, in mid-2009. Then it threw its muscle into promoting the measure, which promised billions in new revenue for members. President Barack Obama signed it into law in March 2010.

PhRMA shrank substantially after that, taking in around $205 million for several years in a row starting in 2010.

Last year it agreed to increase dues by 50 percent to raise an extra $100 million, Politico reported. In an attempt to distance itself from drug companies earning bad headlines, it also decided to bar members that didn't invest a minimum in pharmaceutical research.