Succeeding on Psychiana

Biography charts rise & fall of Frank Robinson, founder of religion that gained popularity during Depression

Moscow’s Frank B. Robinson told his followers that the name for his religion came to him in a dream.

In the dream, he stood at the door to a room that was painted black. Inside the room, a dead man lay on a cot, his hands folded over his chest. Another man stood beside the cot, pointing at the corpse. When Robinson asked the man what he was pointing at, the man answered, “You ought to know. This is Psychiana, the power which will bring new life to a spiritually dead world.”

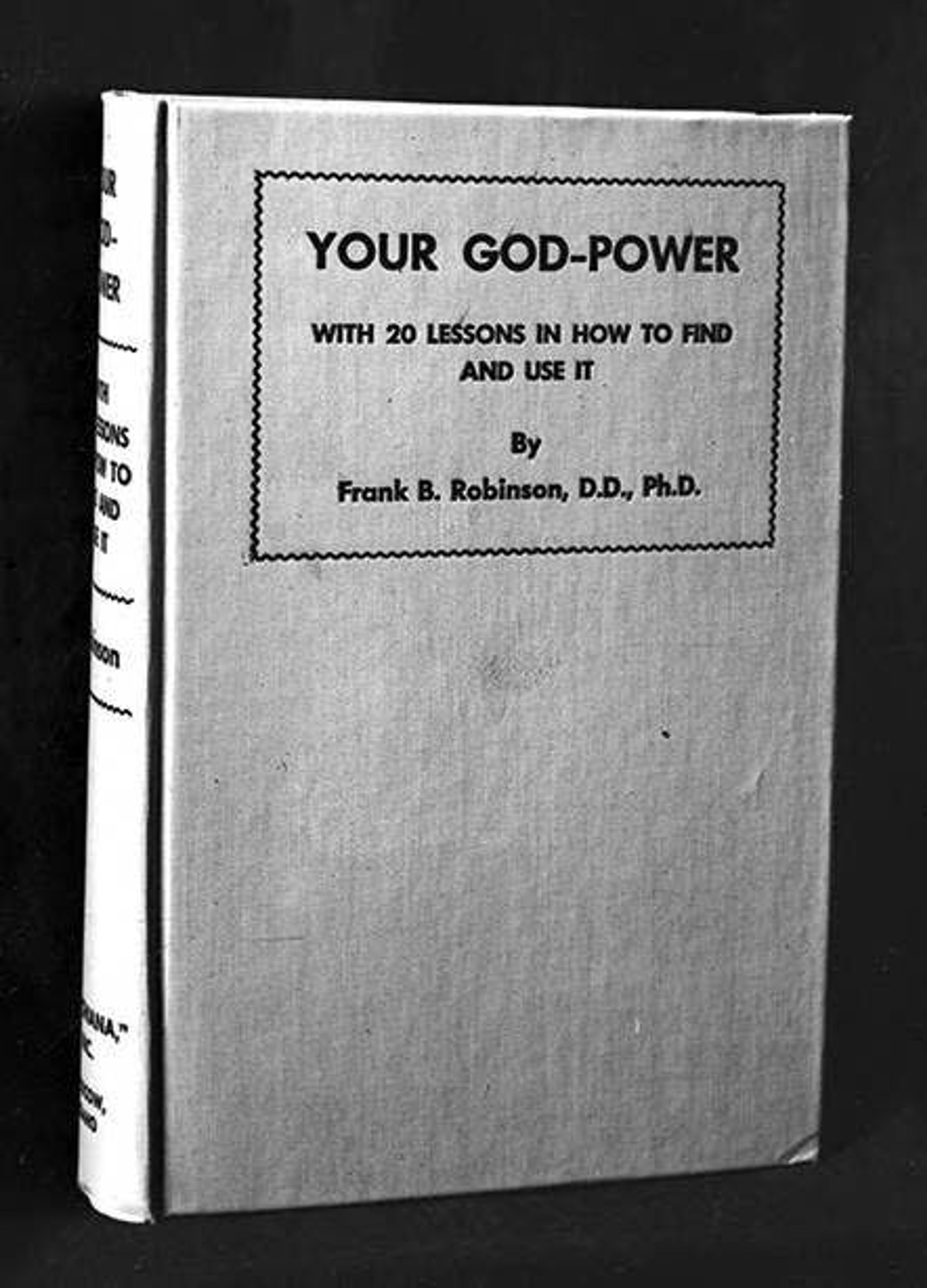

Robinson founded Psychiana a few weeks after the 1929 stock market crash. Through mail-order lessons with a money-back guarantee, he promised to teach people how to access the “God Power” to manifest personal health, wealth and happiness.

Appearances seemed to support his claims. As the economy collapsed, his family’s fortunes rose. The immaculately dressed Robinson drove a green Duesenberg, a rare luxury car owned by just a few people in the world. He became Latah County’s largest employer, and Psychiana was one of the most successful New Thought religions of the 20th century.

But Robinson had a secret past. In “Psychiana Man: A Mail-Order Prophet, His Followers, and the Power of Belief in Hard Times,” Moscow author Brandon Schrand explores his complex legacy. While other historians and some theologians have written about the man and his religion, this is the first full-length biography. It was published this spring by Washington State University Press.

“A lot of people call Robinson a con man. I don’t make any judgments on that; I let the reader decide that. If you read the book, you’ll see he’s a complicated, complicated man. That’s what made him such a fascinating character to write about. If he was totally evil and despicable, that wouldn’t really hold my interest as a reader and researcher,” Schrand said.

Schrand stumbled upon the story of a strange religion founded in Moscow while researching something else. Intrigued, he investigated Psychiana papers and materials housed at the University of Idaho and Latah County Historical Society. The archives contain letters Robinson received from people around the world. Within these letters, Schrand saw the material for a book.

“It was the student voices, along with his story: Their voices, in aggregate, are a snapshot of the world and Great Depression leading into World War II,” he said.

In addition to detailing Robinson’s life, Schrand takes a deep dive into the lives of 20 different students, who came from all walks of life: doctors, farmers, housewives, heavyweight boxers, barely literate writers, college students. Psychiana was a diverse and “truly colorblind” religion, Schrand said. Because it was conducted by mail, people could not be segregated. It included Native American, African and Asian members in its fold.

At the center was Robinson, who came to Moscow in 1928 with his wife, Pearl and son, Alf. He worked as a druggist in a downtown pharmacy, a position he’d held in towns throughout the Pacific Northwest. He was 42 and looking to reinvent himself after a vagabond existence that included time in prison and a history of alcoholism. He told people he was from New York when he actually was from England. It was one of many, many lies.

Robinson’s story is a tale of contradictions, said Schrand, who calls him a “compulsive liar, fabulist and opportunist.” At the same time, he gave money to many people who needed it and donated 60 acres of land to Latah County to create the recreation area Robinson Park. Schrand believes he genuinely wanted to help people.

Lessons from Psychiana

After receiving the name of his religion, Robinson typed out a set of 20 “lessons” on an old typewriter at his home at the Butterfield Apartments. He announced the religion to the public with a newspaper ad that read: “I Talked with God — (Yes, I did, Actually & Literally).”

He proposed to teach the reader, in a series of pay-as-you-go lessons, how to access “the God Power.” His bimonthly teachings would be available to anyone for $1, with guaranteed success to those who followed his instructions.

“Unless you actually do the various exercises I prescribe, chances are you will get nowhere, and only be a loser. … It remains essential that you give me your undivided attention,” Robinson wrote.

Robinson went to Moscow businessmen for startup money to cover the costs of printing materials. Eventually he was bankrolled by an Egyptian cotton merchant who gave him $40,000, about $500,000 in today’s money, Schrand said.

Over time, Robinson’s mass-marketing savvy, grand claims, conversational tone and personal stories of life in Moscow helped endear him to people — but not everyone. Clergymen were especially wary. Robinson did not believe in Christianity and completely disparaged it in his writings, which grew to include books with titles like “America Awakening” and “Crucified Gods Galore.” He told his followers that the only thing that made Jesus special was that he had accessed the God Power and followers of Psychiana could too.

“You’d think that would be crazy and over the top in the 1930s, but people were so disillusioned with institutions that had failed them that someone saying something unconventional, unorthodox, I think it held some appeal for some people,” Schrand said.

Psychiana teachings generally focused on cultivating personal development through daily breathing exercises, meditation, positive affirmations and lesson studies.

“The weird part is, the more you read, the more archaic it becomes; there’s not a lot of depth to it,” Schrand said. “He’d send you a lesson; you pay a dollar; he’d send another lesson. There was a cliffhanger vibe to it. You had to get the next lesson, with no reveal at the end of it.”

The business of religion

People often ask Schrand how Moscow residents felt about Robinson and his religion. He tells them people were generally split into two camps.

“One camp despised him and the attention he brought to the town,” Schrand said.

As Robinson worked to promote Psychiana, he convinced the City Council to allow him to erect two billboards on either side of town that read: Welcome to Moscow, the Home of Psychiana. This didn’t sit well with many residents, Schrand said.

“On other hand, he was the single largest private employer in Moscow during the Great Depression. He hired primarily women and paid them a pretty decent wage for the time period.

He brought in a lot of good paying jobs. It caused a little rift in the community: Do we like Frank Robinson or do we not like him?”

The actual amount of money Robinson made is unclear, because he often inflated his own worth, Schrand said. He owned several buildings, including Turnstone Flats on the southeast corner of Third and Jackson streets. Psychiana headquarters were next door, in what is now a parking lot behind the former U.S. Bank building. He owned Moscow’s newspaper and three drug stores.

“He was quite wealthy, ostentatiously so,” Schrand said.

The trajectory of Robinson’s life changed when he was charged with passport fraud in 1936. The trial at the federal building in Moscow created national headlines as his claims about his life were exposed. The trial drained his coffers significantly, Schrand said. In the mid-1940s he had a heart attack, and his health went downhill. He died in 1948, leaving Psychiana in an awkward position because he’d never named a successor. His wife and son were not members of the religion, and the family closed the business in 1952 because they could no longer afford it.

“This left a lot of students wandering around wondering, what now?” Schrand said.

When Schrand began writing “Psychiana Man” in 2014, he said he had an “academic sense” of what hard times meant.

“Then I was finishing the book during the pandemic and I thought, this is what hard times really look like.”

He sees parallels between those who turned to Psychiana and people today who believe in QAnon or other outsider belief systems.

“I’m not a religious guy myself, but I’ve always been fascinated in why people believe what they believe in,” he said. “All of (the believers in Psychiana) had lost faith in conventional systems — conventional banks, churches, institutions. They were really looking for hope anywhere they could find it.”

Schrand’s book likely won’t be the final word on Robinson and his religion.

When Robinson’s descendants donated his papers and materials to the university and the historical society, they were put in a time capsule. The UI boxes were opened in the 1980s. The society has five boxes that cannot be opened until 2023.

“I’m very interested to see what is in there,” Schrand said. “I’m going to be knocking on their door Jan. 1 at 8 a.m., 2023.”