On to the next chapter

Longtime LCSC professors share latest artworks in Uniontown exhibit

The challenges brought on by the pandemic made many people rethink their lives and make big changes.

For longtime Lewis-Clark State College professors Sean Cassidy and Ray Esparsen, the pandemic was the catalyst for retirement. For more than 25 years, Esparsen taught art and art history at the college, while Cassidy taught video production and photography. The two colleagues and friends will showcase recent works in the exhibit “Transformations,” opening with a reception Sunday at Artisans at the Dahmen Barn in Uniontown.

“We’re calling it transformations because it’s about what we do with the things we find and what we’re doing with our lives at this point,” said Cassidy, who, like Esparsen, is transitioning to being a full-time artist.

“Teaching gives you time to grow and understand your work,” Esparsen said. “The beauty of education and teaching is that you forgo all the glitz and glamour or stardom. You end up reading a lot, thinking a lot.”

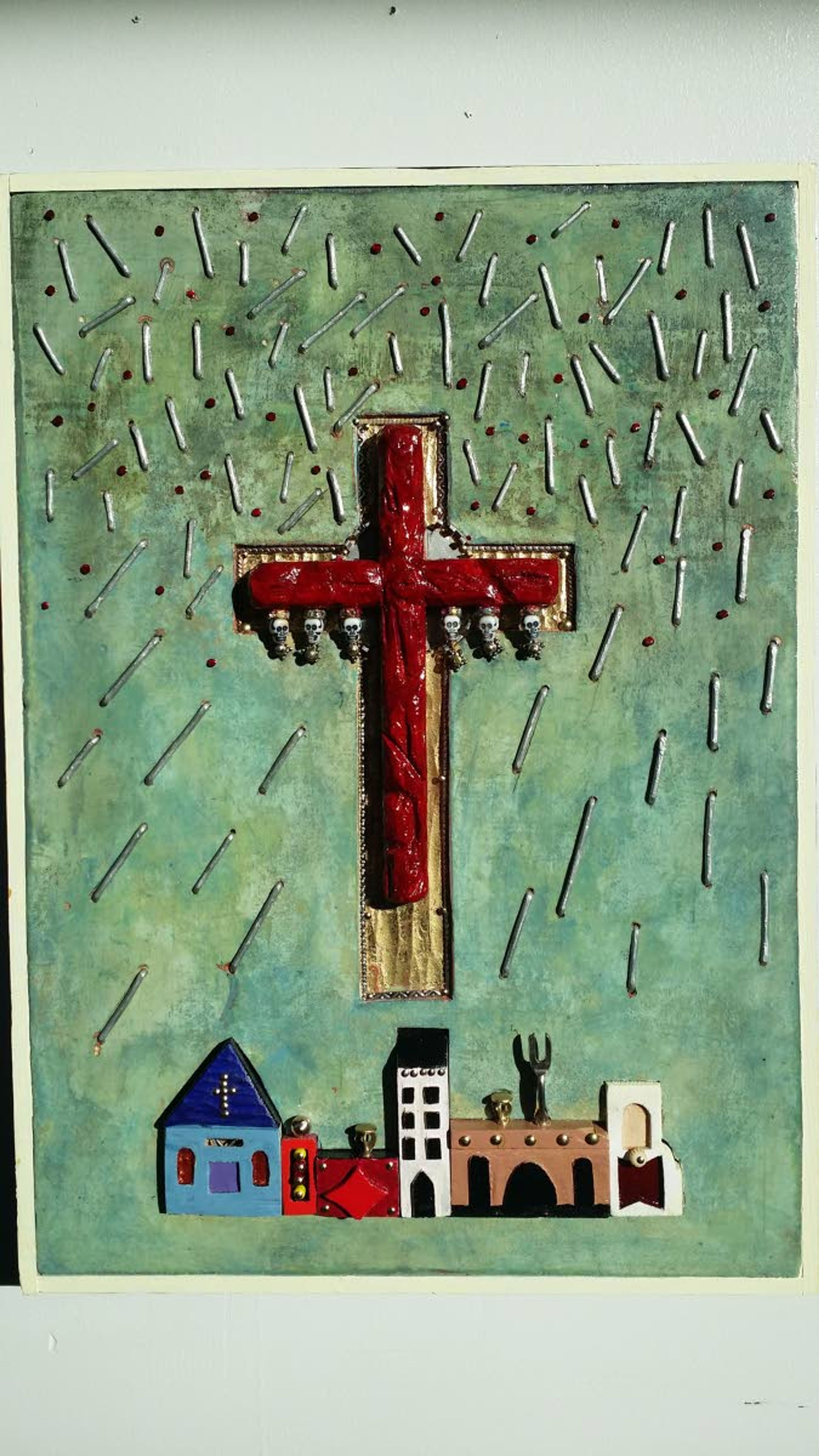

Esparsen’s latest artworks revolve around the concept of retablos — icons created for worship, protection or healing that were part of religious life in Spanish homes and churches during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance eras. While church retablos could be extremely large, elaborate and gilded with gold, retablos for the home often were made from found objects modified to represent a meaningful spiritual event. Esparsen’s retablos are constructed with shiny discarded elements of modern society, things like broken jewelry and computer hardware. The symbol of the cross appears throughout his work, “an icon familiar the world round” loaded with meaning: It can connect people as much as it can repel them, he said.

Retablos were part of a plea to a saint or god, and Esparsen followed a meditative process while creating each of his pieces. He began by thinking of a person in his life whose name starts with the letter “A.” He sent positive energy to that person as he worked. Nothing is glued; instead, each item is cut and fitted. Each piece took about 40 hours to create. He went through the entire alphabet.

“I grew up as a Catholic and was told you never tell someone when you pray for them because that mitigates it. You just try to live that life and be nice to them,” Esparsen said.

People often assume these pieces are about religion or Christianity, but they are not, he said. They are a statement about contemporary throwaway culture.

“We throw away religion and faith, and we do that by having conspicuous consumption,” he said.

The mysteries of life, as seen through the arts, have helped Esparsen appreciate how his own outer and inner life is built upon the labors of others, both living and dead.

“I think artists have always done that, helped people see the obvious in new ways. I think that’s our purpose as artists,” he said.

As a photography professor, Cassidy said his goal was to teach students how to see and how to pay attention.

His photographs in the exhibit are of objects from nature that most people would never notice, like broken twigs or leaves. He rearranges and photographs them with the aim of shifting the viewer’s perspective on what they are seeing.

“What I see are the spirits within the things I find,” Cassidy said. “When I see a face staring at me on the ground, I pick it up and bring it home and see if I can create the rest of it around the face.”

While he once photographed flowers, he now looks for something within the flower, “like seeing a horse in a cloud.”

Cassidy created these works during the pandemic. Unable to travel, he looked for things to photograph while walking around his neighborhood, sometimes with Esparsen.

Both men’s decision to retire in January was influenced by the pandemic.

“Part of the reason I retired was that I was spending more time with technology than I was with the students,” Cassidy said.

Esparsen agreed, “It’s fun and great to use but it’s such a surrogate, a facsimile.”

They will miss working with students and are unsure if the college will fill their full-time positions or leave them vacant as a cost-saving measure. They hope the college continues its same level of support of the arts.

People who go into the humanities work within a different ideological framework than those who go into business, Esparsen said. “I think the arts are probably the most difficult thing to teach. In science you can teach facts; in math there’s a right answer.”

In the arts, however, the answer is often, “maybe.”

“Art is a lot like prayer,” he said. “You can’t tell someone they’re praying wrong.”