counting on the INhuman TOUCH

Cottonwood manufacturer's new robot terminates Chinese competition to bring back another product made in the U.S.A.

COTTONWOOD - A three-armed robot has helped Uhling Products Co. in Cottonwood win back a job it lost to China.

The company is once again making an aluminum switch bracket for a dental supply business as orders rebound following the recession. The bracket holds an activation switch for water and air tools frequently used to clean teeth.

Uhling's choice to grow with a machine sheds light on why, even as the economy regains strength, job creation has been slow.

"We compete globally. That's part of the reason I decided to go with automation," said Jeff Uhling, who acquired the company in 1988. "We wouldn't have gotten the parts back from China if we were using human labor."

What's happening at Uhling Products is being repeated other places in north central Idaho, said Kathryn Tacke, an economist with the Idaho Department of Labor. "Unlike most other inputs into production, the cost of technology keeps going down. ... Places that employ as few as four or five can afford things that they wouldn't have been able to dream of 10 years ago."

While north central Idaho now has a few more manufacturing employees than it did before the recession, the volume of goods they make has risen significantly, Tacke said. "We're producing a whole heck of a lot more."

The trend is in play at Uhling Products, where the 30 employees it's had for about five years now make 10 to 20 percent more than they did prerecession.

The company fabricates parts for about 100 customers - mostly in the United States - that manufacture things such as cranes, hand tools and gun mounts for anti-missile systems on battleships. Normally the items are sold under brand names other than Uhling.

Less than 10 percent of the items are made by the robot, but Uhling believes that's where at least some of the future expansion of his company will be.

Growing the payroll would be expensive, especially with the rising costs of health care, and it's becoming increasingly difficult to find individuals with a combination of computer and machine shop skills willing to live somewhere as rural as Cottonwood, he said.

His employees' knack for identifying and meeting the needs of new markets, partly by mastering new technology, is what has kept the company thriving for decades, Uhling said.

Back in 2007, a cabinet press, Uhling's only proprietary product, was the company's biggest-selling single item. When the housing market tumbled, demand for cabinets and the tool declined.

About the same time, a dental supply company that had been Uhling's largest customer abruptly changed suppliers, he said. "They had to get more competitive, so they went to China for lower prices."

The near-perfect record for quality that Uhling earned in 15 years didn't sway decision-makers, he said.

Uhling recalibrated, this time seeking smaller-volume customers and eventually landing a rifle scope maker as a major customer. Of 125 parts in the scope, Uhling makes 30, he said.

The robot was acquired about a year ago so the business could once again compete for large jobs. The robot grabs blanks, positions them more than once in a computerized, numerically controlled machine, unloads the finished pieces and places them on a conveyor belt.

As novel as the robot seems, it's really just the latest progression in machinery that keeps getting refined to do work faster, Uhling said. "The robot is extending our hours of productivity by running when no one is here."

The computerized, numerically controlled machine used with the robot is one of the most recent generations in a series of the equipment, Uhling said.

The first ones Uhling had operated at 300 inches per minute and now that's up to 2,100 inches per minute. People used to change holders for cutting tools, taking about one minute each time. Now that happens automatically in 1.6 seconds, Uhling said. "I think that's astonishing."

The dental supply company was one of the first customers Uhling called after his company acquired the new technology. The robot doubled the output and all but eliminated the labor costs. But initially, the dental supply company didn't seem that interested.

Other customers were, however, and Uhling used the robot for high-volume jobs such as archery and firearms components.

Then came February, Uhling said. "They called and said, 'How quickly can you start?' "

No explanation was offered and after some intense negotiations on price, Uhling was once again making brackets, he said.

One thing the robot won't be used for is jobs that Uhling was already completing with its staff, he said. The company, for example, can't achieve the quality the rifle scope maker requires without people.

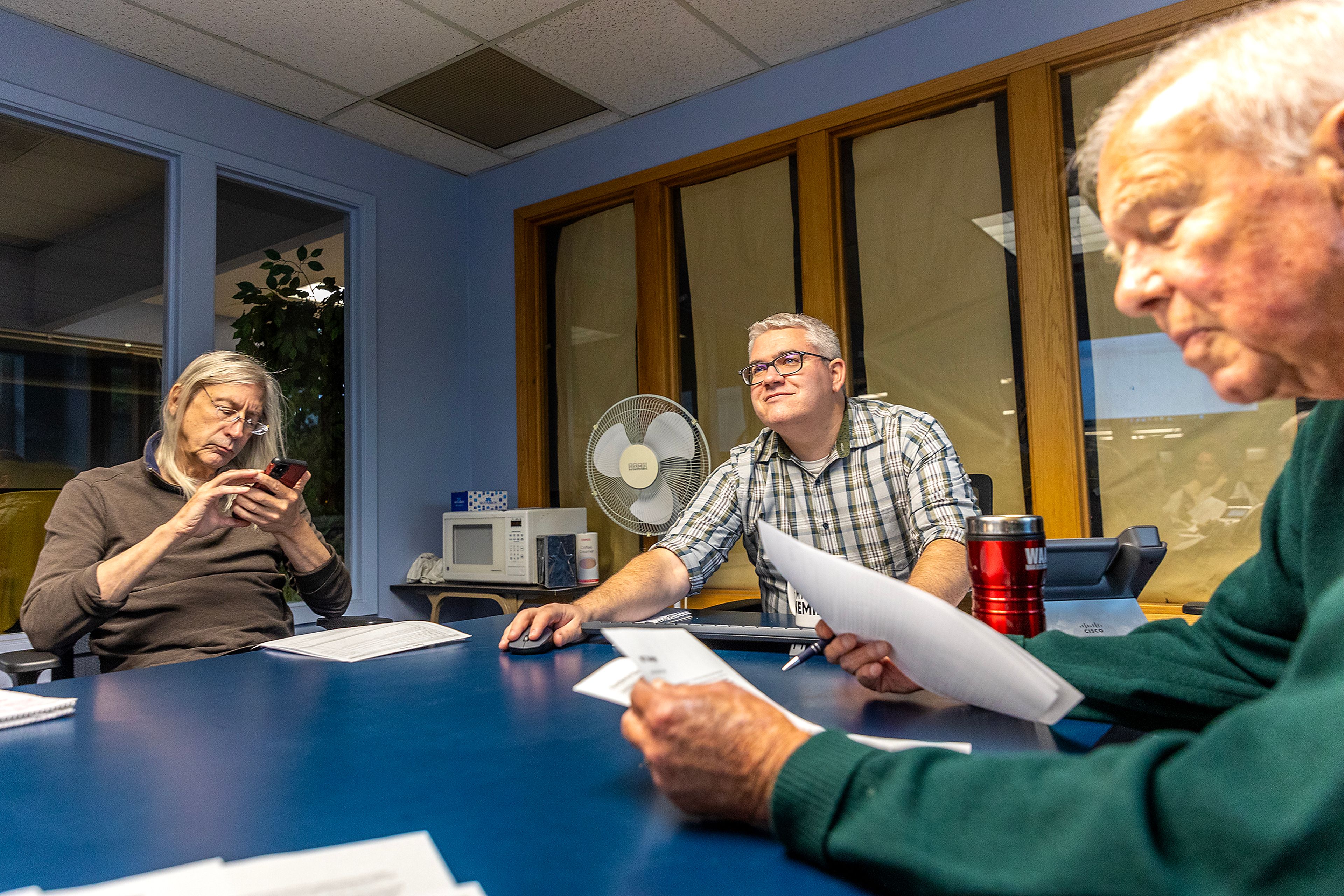

Employees still do promotions, program equipment, monitor machines, maintain quality and process finished goods, Uhling said.

"They have to do anything that isn't anything you repeat over and over again," Tacke said.

The robot has taken some adjustment for the staff at Uhling, which works in three shifts - two during the week and a third on the weekends.

"You need to run the automated machines that much to make it pay and to get it to the customer on time," Uhling said.

Tom Sonnen, who programs the robot and supervises the machine shop, had to learn an entirely new computer language. But because of how the robot is configured, the only way to practice was on the factory floor, not at an office computer.

The robot is one of four stations that Matthew Matalamaki oversees. "It's really user friendly. We need to get more of them."

His boss is already thinking about that.

Before he does, he'll probably have to construct an addition. The robot now operates in the shipping room.

---

Williams may be contacted at ewilliam@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2261.